On 23 February 33 BCE, the Queen of Egypt, Cleopatra VII, issued a royal ordinance granting financial privileges to a Roman absentee landlord. These privileges include tax exemptions and protection of his workers and other property from various impositions.

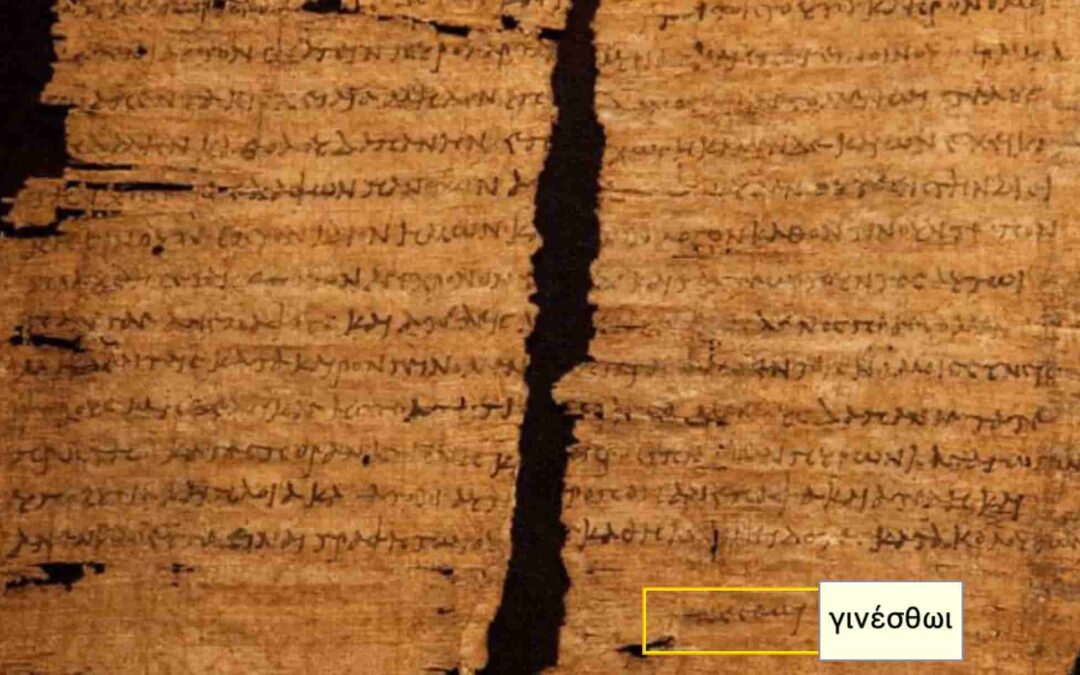

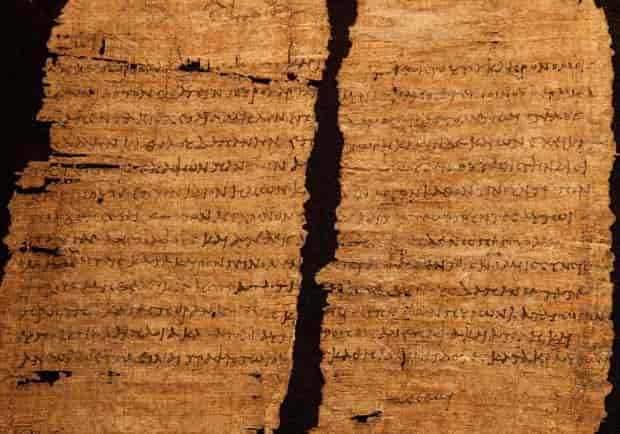

More than the economic implications of this document, and the role of absentee Roman landlords in late Ptolemaic Egypt, this papyrus document has gained most renown over the past two decades because of a single word at the end of the text, which may have been written in Cleopatra’s own hand.

Unfortunately, the name of the landlord in question is mostly damaged and there is some disagreement regarding his identity.

Peter van Minnen reads here the name of a Roman general, Publius Canidius Crassus, a well-known figure connected with Antony.

However, Klaus Zimmermann reads the name Quintus Cascellius, an otherwise unattested member of a known family.

This issue highlights some of the problems inherent in dealing with papyri: ink traces can be read in different ways, by different scholars, resulting in considerably different interpretations in texts.

Technical Details

- Provenance: Written in Alexandria; found in Abusir el-Melek.

- Date: 23 February 33 BCE (year 19 of Cleopatra’s reign)

- Language: Greek

- Collection: Berlin, Papyrus Collection of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Duane W. Roller (2010, p. 134) provides a description of this papyrus document from late Ptolemaic Egypt, dated to the reign of Cleopatra VII:

In February 33 B.C. she approved an order granting certain tax exemptions to Publius Canidius Crassus, who had been with Antonius for a decade and would be senior commander of the land forces at Actium.

The relevant document is a papyrus recovered from mummy wrappings and first published in the year 2000.

Canidius was allowed to import 10,000 artabas of wheat and 5,000 amphoras of wine tax free, and the lands that he owned in Egypt were also exempt.

What has excited interest is the subscript in a different hand: γινέσθωι (“make it happen”). There is little doubt that this is the writing of the queen herself, as there was a tradition in Ptolemaic Egypt of countersigning by the monarch, in part to avoid forgery of official documents.

This autograph of Cleopatra VII certainly is one of the more exciting discoveries of recent years: the only other known royal autographs from antiquity are of Ptolemy X and Theodosios II, both somewhat less interesting than the queen.

The document also indicates the dichotomy that still existed at the very end of the Ptolemaic era between the rulers (and their Roman allies) and the ruled, where the former continued to obtain special privileges.