After the assassination of Amenemhat I, and fearing possible reprisals, Sinuhe flees Egypt and takes refuge in the Middle East, where he will become a rich and respected man. Thus begins the Story of Sinuhe, one of the most famous tales of ancient Egypt.

“The residence was silent, hearts afflicted, doors closed, courtiers with heads on their knees and people in laments.”

With this description of the atmosphere of desolation prevailing in the court of ancient Egypt due to the death of Amenemhat I begins the History of Sinuhe, the best known literary composition of ancient Egypt and considered a masterpiece.

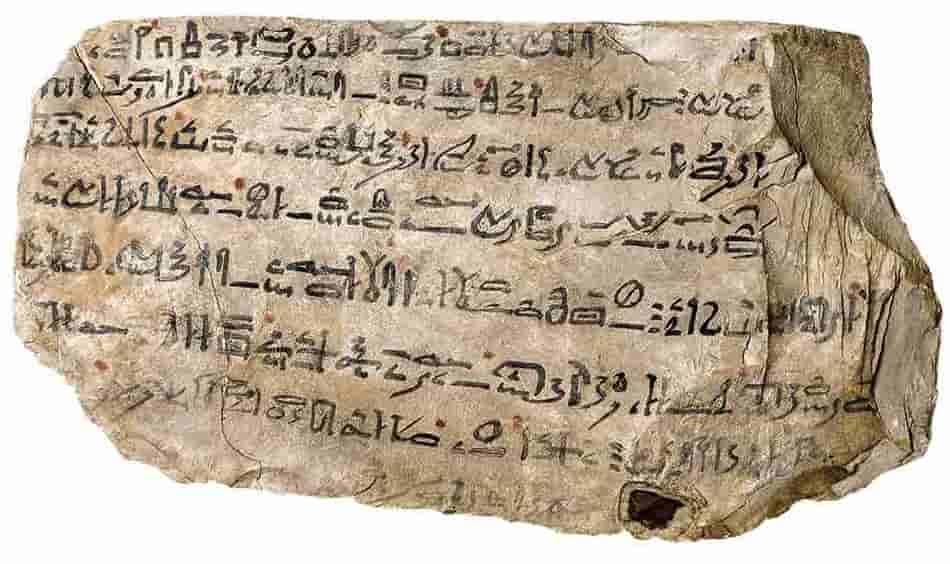

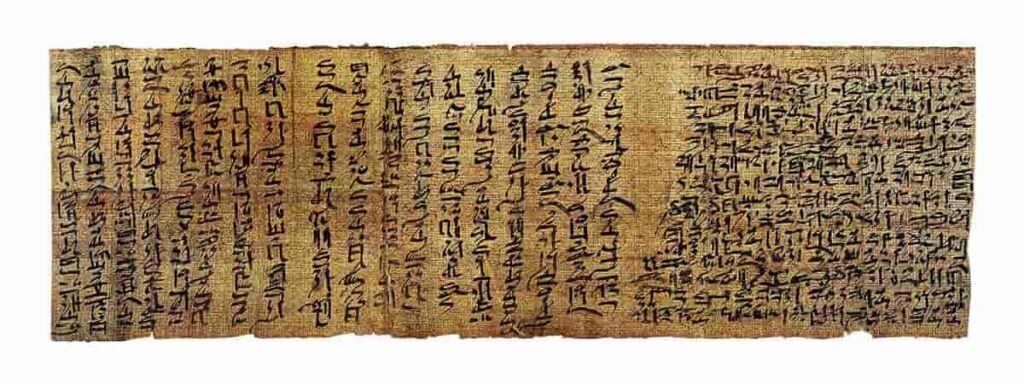

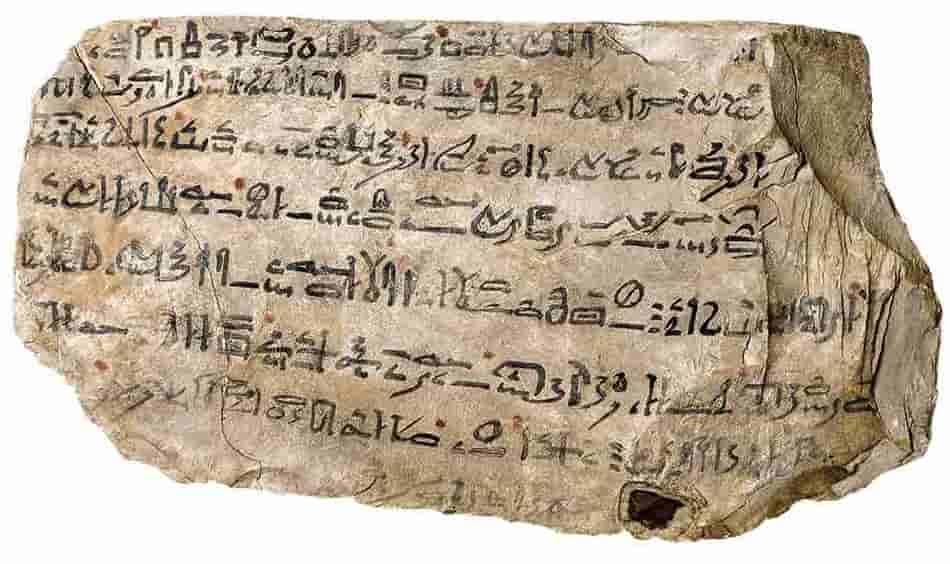

The multiple copies that are preserved of this text demonstrate the popularity it had in Pharaonic times. It was widely used by scribe’s apprentices, which is why up to 28 ostraca (ceramic or stone fragments used for writing and drawing) and seven papyri that collect various parts of the story have been preserved.

Of no other Egyptian literary text do we have such a large number of copies.

Thanks to the ostraca and the papyri it has been possible to reconstruct from beginning to end the tale of the History of Sinuhe, whose plot takes place at the beginning of the 12th dynasty, from the death of Amenemhat I and throughout the reign of his son Senusret I.

The text is full of action, with insertions of dialogues that increase its liveliness, and even with transcripts of the letters exchanged between the pharaoh and the protagonist, which gives more realism to the narration.

All the known versions of Sinuhe’s story were embodied in Hieratic writing, a simplification of the Hieroglyphic and the one most used by scribes.

They used to write in black ink, using red for headings or main sentences or for revisions and corrections that teachers could make on the original writing.

These details, as well as the personal calligraphy of each scribe, are observed in the various preserved copies. On the other hand, the style of the text is framed for the most part in the genre of the narrative verse. In fact, in some versions the scribe marked dots in red ink to separate the main sentences, perhaps to form couplets.

A Nobleman in the service of the pharaoh

The protagonist of the story is Sinuhe, whose name means “son of the sycamore”, a character who is presented at the beginning of the text as the:

“Nobleman, leader, judge, bearer of the royal seal, administrator of the king’s districts in the lands of Asians”, “true acquaintance of the king, his beloved, follower and servant of Queen Neferu, the great royal wife of Senusret I”, which denotes his importance and his closeness to the pharaoh and his family.

On the other hand, this introduction tries to resemble the autobiographical texts usually inscribed in many tombs and in which the ancient Egyptian showed off his curriculum.

The action of the History of Sinuhe begins with the death of Amenemhat I in the year 30 of his reign, a regicide that is not described as such in the story, but that other historical documents speak of.

The pharaoh was assassinated in his palace while he slept, as described in Amenemhat’s Instructions, a text in which the spirit of the king recounts his death to his son and successor, and advises him on matters of government.

The History of Sinuhe also does not indicate whether the unexpected death of Amenemhat caused riots in Itj-tawy, the capital founded by the pharaoh, as if it had been decided to drop a veil of mystery about the death of the king and Sinuhé’s subsequent reaction. .

It is indicated in the story that Senusret I was returning from a campaign against the Libyans at that time, so messengers were sent to inform him of his father’s death.

Faced with the terrible news, and without being explained in the text, Sinuhe, who accompanied the army of the crown prince, reacted as if some feeling of guilt accompanied him:

“A tremor ran through my body and I jumped off looking for a hiding place; I got between two bushes.”

Sinuhe’s escape

Sinuhe begins his strange escape by going up the Nile from the west of the Delta to the Giza plateau, and at the height of a town called Negaur he crosses the river in a rudderless raft, taking advantage of the west wind.

After passing through the Gebel Ahmar quarry, near present-day Cairo, he will continue along the east of the Delta, to the Ruler’s Walls, on the eastern border of the country, a kind of fortification system built by Amenemhat I to prevent incursions from Asian peoples.

When he reaches the Bitter Lakes area, north of the Suez Isthmus, Sinuhe is on the verge of death:

“I had a fit of thirst. I was dehydrated, my throat was parched. I said to myself: ‘This is the taste of death”.

In that state of prostration he is found by nomads who save him. Numerous documents from this time speak of the peaceful arrival of Asians to the Delta region, either for commercial reasons – as shown in a painting from the tomb of Governor Khnumhotep II in Beni Hassan – or simply to spend time in the fertile alluvial lands. which, especially in times of famine, served as pasture for their cattle.

Once in Qedem, near Byblos, Sinuhe meets Amunenshi, the ruler of the Upper Retenu region in Syria.

When asked about the situation in the palace and about his strange trip, Sinuhe once again ignores the serious events, but at the same time emphasizes his innocence:

“I was not accused, I was not spat on. No criticism was heard, my name in the mouth of the herald. I don’t know what led me to this foreign land.”

Sinuhe, immediately afterwards, describes the greatness and good manners of the new pharaoh, Senusret I, and advises Amunenshi to write to him and be loyal to him as he was with his father Amenemhat I, with whom he had had diplomatic relations.

At this moment, nothing suggests that Sinuhe, who in Egypt had been fearful and elusive, even cowardly, will distinguish himself by the opposite in his new country.

Brave soldier

Our protagonist joins the tribe of prince Amunenshi and marries his first-born, thus becoming a tribal chief and going to live in a border place called Iaa, which is described as an authentic orchard, a fertile land, rich in honey, oil, fruits, cereal and livestock.

After long years, even his sons will become tribal chiefs. Sinuhe will also fight against the Asian Bedouin as commander of the troops of the ruler of Upper Retjenu, continually proving his worth.

One day, a hero and champion of Retjenu challenges Sinuhe and they agree to fight at dawn. The tribes of both will remain expectant following the tribal rules, according to which the authority is personal since the future of the tribe will be marked only by the result of the combat between the two chiefs.

This is the climax of history: Sinuhe manages to defeat his rival and take all his belongings from him, reaching the moment of greatest glory in his adopted country.

But when his stay there is prolonged and old age arrives, his heart continues to heavy for being far from Egypt:

“My house is beautiful, my position is privileged, but my thoughts remain in the palace. Oh God! Once this flight has been ruled, be merciful, without a doubt you will allow me to see again the place where my heart has always remained […] What is more important than my body being buried in the land where I was born? “.

Don’t die in a foreign land

Sinuhe’s desire to return to Egypt reaches the ears of Pharaoh Senusret I, who in a letter expresses his desire to return:

“Do not die in a foreign land, may the Canaanites not bury you, may they not wrap you in a coffin […], think of your body and come back “.

Senusret I does not raise accusations or reproaches, but in his response to the royal letter, Sinuhe insists on not knowing what motivated him to flee:

“I had not foreseen this flight, it was not in my heart, I had not premeditated it, I do not know what brought me to this place […] I was afraid, although I was not being pursued.”

Before returning to Egypt, Sinuhe leaves his property and command of the tribe to his eldest son. The return is through the Ways of Horus.

Once in the palace, the exile prostrates himself before the king. The vision of the pharaoh shocks Sinuhe, who relives his fears and leaves his life in the hands of the pharaoh:

“I was like a man trapped by darkness, my Ba was gone, my body fainted, my heart was not in my body, and did not distinguish between life and death.”

After his years in Syria, Sinuhe’s appearance, dress and his physical state makes that not even the Egyptian princes are able to recognize him.

But the king: ” He is not to be afraid. He will be a friend among the nobles, he will be placed in the midst of the courtiers .”

Upon leaving the palace, Sinuhe is escorted to the house of a nobleman, where he is groomed and decked out:

“Years were removed from me, I was shaved, my hair combed. I abandoned the dirt of the desert and the clothes of those who walk the sand, and I dressed in linen, I anointed myself with the best oil, and slept on a bed.”

He is given a house and is provided with abundant daily sustenance, and – most importantly – he is granted a stone and decorated tomb, with a complete trousseau and the funeral service assured.

Thus he will be able to end his days in Egypt, where his heart had always remained. “I remained under the favors of the king until the day I left.”

Versions of Sinhue’s story

The oldest and most complete version of Sinuhe’s account that we know of is the one preserved in the Berlin 3022 papyrus, which was discovered in a Theban tomb in the mid-19th century.

It has 311 lines of text, although the first few are missing. This papyrus dates from the 12th dynasty, around 1800 BC, other papyri dating from that same dynasty that only provide small parts of the story.

Another very complete example is the Berlin 10499 papyrus, from the 13th dynasty (around 1700 BC), which was found by James Quibell inside a box filled with medical, literary and administrative texts in a tomb near the Ramesseum.

As for the ostraca (ceramic or stone fragments), Most of them come from the Deir el-Medina site and are probably from the Ramses period, that is, more than six hundred years after the Berlin 3022 papyrus. In contrast, an ostracon from the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, with 130 lines of text, preserves much of the story.

Source: National Geographic