Located approximately 250 kilometers south of Aswan, near the Second Cataract of the Nile, Abu Simbel stands as a testament to ancient Egypt’s architectural marvels. Nestled amidst a striking landscape, this site features two prominent rocky formations long revered as sacred. It was during the reign of Pharaoh Ramses II that Abu Simbel became home to some of ancient Egypt’s most exceptional temples.

Discovery of Abu Simbel temple

The first whispers of Pharaonic monuments at Abu Simbel reached the Western world through the intrepid Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt. Known for his earlier discovery of Petra in 1812 during travels across the Near East, Burckhardt’s journey led him to Abu Simbel on the morning of March 22, 1813, accompanied by his guide Mohamed Abu Saad from the village of Derr.

In his travelogue “Travels in Nubia,” Burckhardt recounts his arrival at what he referred to as “Ebsambal,” drawn by the grand descriptions shared by locals and Bedouins. Ascending a hill on camelback, Burckhardt was immediately struck by the sight of six colossal statues carved from the rock, depicting figures in a standing posture.

Descending towards the structure, Burckhardt realized it was merely the facade of a larger temple complex carved deep into the mountainside. Overwhelmed by curiosity, he explored what is now known as the Small Temple of Abu Simbel, meticulously documenting his findings with notes and a rudimentary sketch of the temple’s layout. This documentation marked the beginning of extensive scholarly interest in these monumental constructions.

As Burckhardt prepared to depart from Abu Simbel, his gaze turned southward, where he was met with an astonishing sight: “My eyes were drawn to the visible remains of four immense colossal statues,” he noted, “nearly buried under sand.” The statues’ posture, whether standing or sitting, was difficult to discern amidst the sandy veil.

Burckhardt’s encounter marked the first Western observation of the grandiose representations of Ramses II adorning the facade of the Great Temple of Abu Simbel. He was the inaugural witness to its monumental scale, meticulously describing the shape of the visible reliefs and hieroglyphics, and reveling in its breathtaking beauty.

The news of these magnificent monuments spread rapidly, capturing the imaginations of travelers and adventurers alike. On October 20, 1815, a small expedition led by William John Bankes, aimed at reaching the Second Cataract of the Nile, halted at this remarkable site. They also visited the Small Temple, but a substantial sand dune obstructed access to the Great Temple, nearly engulfing it entirely.

Accompanied by the geologist and draughtsman Frederic Cailliaud, Bernardino Drovetti, serving as the French Consul General, embarked on a voyage up the Nile, reaching Abu Simbel in March 1816. Drovetti’s primary objective was to uncover the massive colossi buried under the sand and explore potential access points to the interior spaces of the temple. Despite his efforts, he encountered resistance from the local population, which thwarted his plans for excavation.

This setback created an opportunity for Giovanni Battista Belzoni, an Italian with a colorful background that included stints as a strongman at traveling fairs and expertise in hydraulic engineering. Belzoni’s destiny, however, would be intertwined with the dawn of Egyptology.

Following Drovetti’s unsuccessful attempts, Belzoni made his way to Abu Simbel. He leveraged his diplomatic acumen to establish rapport with nearby communities, crucial for mobilizing labor to clear the vast quantities of sand obstructing the site. Yet, challenges persisted, exacerbated by local superstitions warning of dire consequences should the colossi be disturbed.

Amid mounting tensions and logistical difficulties impeding progress, Belzoni ultimately chose to withdraw from the project, leaving Abu Simbel behind.

However, just a few months after his initial attempt and unwilling to accept defeat, Belzoni resumed his mission to Abu Simbel in the summer of 1817, this time under the patronage of Henry Salt.

Despite numerous challenges, Belzoni’s unwavering determination prevailed. He successfully oversaw the excavation efforts that reduced the massive sand dune by approximately 15 meters. Concerned about potential collapse or entrapment, Belzoni ingeniously fortified the entryway with a palisade constructed from palm trunks and stakes, and stabilized the sand with water. After days of intense labor, on August 1, 1817, he finally breached the interior of the Great Temple of Abu Simbel.

“On the first day of August, early in the morning, we approached the temple with great anticipation of exploring this newly uncovered marvel. Unlike our previous attempts, this time we ventured forward without our crew,” Belzoni recounted.

“We quickly widened the entrance and stepped into one of the most magnificent and expansive excavations, unparalleled in Egypt except perhaps by the recently discovered tomb in the Valley of the Kings.”

“At first glance, it was clear we were standing in an immense space, but our excitement grew exponentially as we beheld one of the most remarkable temples adorned with extraordinary carvings, paintings, colossal statues, and more.”

Between 1818 and 1819, efforts persisted to uncover the full extent of the Great Temple’s facade at Abu Simbel. It was during this period that the true dimensions of the temple became fully apparent, confirming that the colossi were seated on thrones rather than standing. However, despite initial progress, the relentless encroachment of the sand dune soon obscured much of the structure once more, perpetuating ongoing challenges.

In the wake of these initial discoveries, Abu Simbel swiftly emerged as an indispensable destination for both scholars and adventurers alike.

Jean François Champollion, renowned for deciphering hieroglyphics and regarded as the father of Egyptology, was profoundly moved by his encounter with the temples. He expressed his sentiments upon leaving:

“As I reached the middle of the river, I cast a final glance at the Temple of Hathor, which appeared infinitely grander from a distance, allowing me to appreciate the entirety of the six colossal statues, crafted with remarkable skill. I then bid farewell to the statues adorning the facade of the great temple, their massive forms seemingly growing larger as I moved away. I could not shake a profound sense of sadness upon departing from this exquisite monument, the first temple I have left, never to behold again.”

Abu Simbel Temples

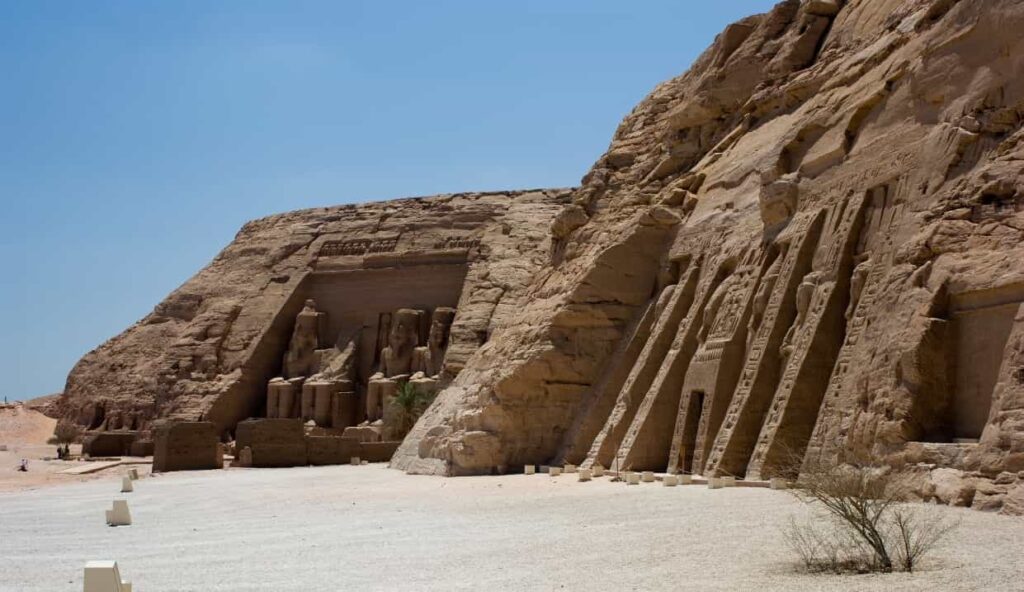

The choice of Abu Simbel, nestled between the majestic hills of Meha and Abshek, remains shrouded in mystery from Pharaonic times. These twin peaks, towering over the Nile’s edge, likely captivated ancient Egyptians with their natural grandeur and perhaps offered sanctuary from the relentless sun. Legends suggest that the rocks themselves may have borne shapes reminiscent of revered gods or symbols, drawing pilgrims and kings alike to inscribe their presence even before Ramses II.

It was Ramses II, however, who transformed Abu Simbel into an unparalleled marvel, crafting a monumental complex that stands as a testament to Pharaonic ingenuity and artistic prowess. What sets Abu Simbel apart is its unique construction: two sanctuaries hewn entirely from the living rock of the mountain, a rare architectural feat known as the speos type. While other Egyptian temples, like those at Deir el-Bahari, feature sanctuaries partially carved into cliffs, none match the sheer scale and precision of Abu Simbel.

The Small Temple at Abu Simbel

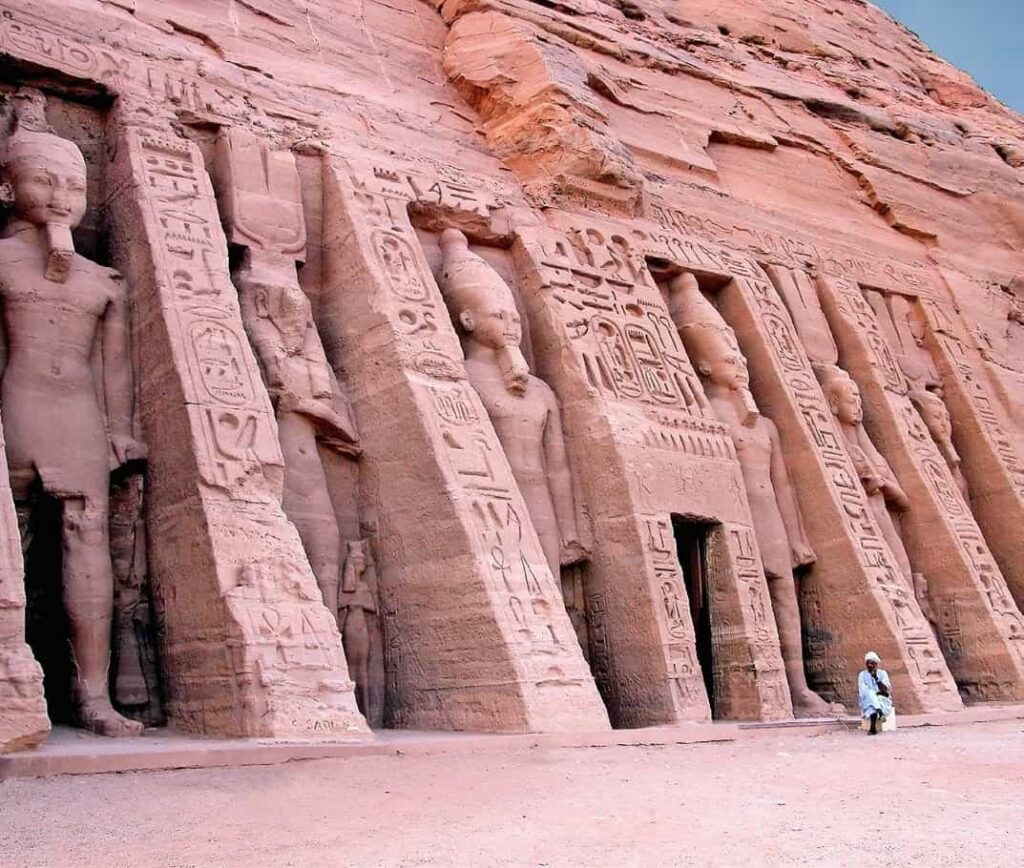

Nestled deep within the limestone heart of the Ibchek promontory in southern Abu Simbel stands what is known as the Small Temple—a misnomer given its impressive dimensions. Stretching 28 meters in length and rising 12 meters high, its facade commands attention, adorned with six colossal statues nearly 10 meters tall, seeming to beckon all who approach.

Dedicated by Ramses II to his beloved Great Royal Wife, Nefertari, the Small Temple is a testament to their enduring love and mutual respect. Among the four representations of Ramses II adorning its walls, two are equal in size to the king himself—depictions of Nefertari, elevated and honored as only a queen could be. Accompanying these grand images are smaller figures, representing the sons and daughters born of their union, immortalized in stone for eternity.

What sets this temple apart is not just its architectural grandeur, but the profound symbolism of its construction. Ramses II’s decision to dedicate such a magnificent structure to Nefertari speaks volumes about their relationship, portrayed not just as a political alliance but as a deeply personal and loving bond. Inscriptions on the temple facade proclaim it as a monument to “Nefertari, beloved of Mut,” underscoring the role of love as the driving force behind this extraordinary testament to their union.

Stepping beyond its majestic facade, the interior of the Small Temple at Abu Simbel unfolds with elegance and a welcoming ambiance that mirrors its outward grandeur. Six towering pillars, adorned with intricate Hathoric ornamentation, dominate the sacred space. Hathor, depicted with her distinctive frontal face, symbolizes the divine fusion of Nefertari, the beloved consort of Ramses II, with the goddess Hathor—a tradition steeped in millennia of Egyptian civilization. This union mirrors the mythological harmony of Horus and Hathor, embodying royal devotion and divine protection.

Inside, the walls of the temple are a canvas of well-preserved reliefs, some still adorned with traces of polychromy. The rich iconographic tapestry includes depictions of various deities and scenes that exalt Ramses II’s triumphs over adversaries or his coronation rites. Amidst these divine narratives, Nefertari emerges prominently, depicted face-to-face with the gods, presenting offerings, and performing sacred rituals with the sistrum—an emblematic instrument in Egyptian liturgy, particularly associated with priestesses.

Numerous reliefs depict intimate moments between the queen and the pharaoh, illustrating Nefertari’s steadfast support and companionship during Ramses II’s campaigns. One poignant relief captures Nefertari tenderly offering a menat necklace to Ramses II, an act laden with symbolism linked to Hathor, the goddess of love and joy. Hieroglyphic inscriptions accompanying the scene proclaim, “I give you all life, all power, and all health,” encapsulating the queen’s devotion and wishes for the pharaoh’s eternal prosperity.

Delving deeper into the inner sanctum of the Small Temple at Abu Simbel, visitors pass through a vestibule leading to two chapels. Here, a remarkable scene unfolds where Hathor, revered as the Lady of Ibchek, and Isis, the Mother of God, bestow a divine crown upon Nefertari. This portrayal, unprecedented in Egyptian iconography, underscores the queen’s exceptional status, depicted holding the ankh—an emblem symbolizing her divine essence. Through this sacred coronation, Nefertari ascends to the title of “Hathor, Lady of Ibchek, Lady of Heaven, Sovereign of all the Gods,” solidifying her place among Egypt’s revered deities.

Further within the sanctuary’s innermost recesses, a profound high relief emerges from the rock, depicting Hathor in her bovine form. Here, the goddess is intertwined with Nefertari herself, portrayed in a protective stance over Ramses II, albeit on a smaller scale. Despite some damage, Ramses II remains visible beneath the divine cow’s snout, accompanied by an inscription near the cow’s ears proclaiming him as “Lord of the Two Lands, beloved of Hathor, Lady of Ibchek.”

The Great Temple of Abu Simbel

Situated approximately 150 meters from the Small Temple, atop the Meha hill, the Great Temple of Abu Simbel commands attention with its east-facing facade, subtly tilted as if Ramses II himself gazes towards the nearby monument dedicated to his beloved wife, Nefertari.

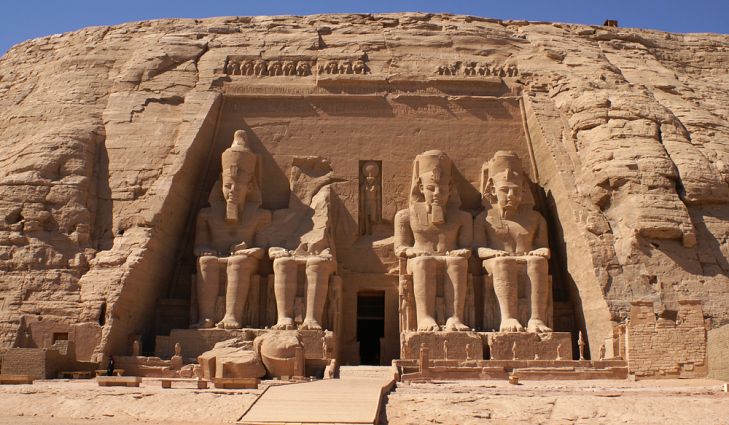

This monumental structure is a testament to ancient Egyptian grandeur, its dimensions awe-inspiring at every turn. Along the upper edge of the facade, a row of baboons stands over two meters tall, their hands raised in a gesture of worship—a symbolic homage to the rising sun. Towering even more impressively are the colossal figures of Ramses II, reaching an imposing 20 meters in height. Here, the term “pharaonic” truly embodies its most authentic meaning, as Abu Simbel stands as an epitome of ancient Egyptian greatness.

The entire facade, intricately carved into the mountainside, takes on a trapezoidal shape reminiscent of traditional Egyptian temple architecture. This design not only adds to the temple’s monumental presence but also enhances the illusion of height, creating a sense of awe-inspiring grandeur.

Of particular note are the four colossal representations of Ramses II, each exuding a powerful presence that borders on the mesmerizing. Enthroned and adorned with royal crowns, Ramses II gazes solemnly towards the east, embodying the eternal cycle of the sun’s daily journey. At his feet, in a scene of familial apotheosis, stand various members of his dynasty: princes, princesses, his mother, and prominently, his beloved wife Nefertari, depicted with reverence and grace.

Adorning the center of the facade of the Great Temple of Abu Simbel, above its monumental doorway, stands a striking depiction of a god with a falcon’s head, crowned by a solar disk embellished with a cobra. This majestic figure represents Ra, the powerful sun god, embodying divine kingship and cosmic order.

Adjacent, though less well-preserved, is the figure of a goddess adorned with an ostrich feather atop her head—this is Maat, the goddess of truth, justice, and harmony. Together, these sculptures in the niche form a cryptic message: User-Maat-Ra, a condensed form of Ramesses II’s Throne Name, “Usermaatra Setepenra” (Mighty Maat of Ra, Chosen of Ra).

Surrounding this central iconography are bas-reliefs portraying Ramses II presenting offerings, a symbolic act laden with deeper meaning. Each offering, intricately detailed, serves as a cryptographic expression of the pharaoh’s own name—User-Maat-Ra—further reinforcing his divine connection and role as a living manifestation of cosmic balance and kingship.

In these reliefs, Ramses II is depicted offering tribute to Maat, symbolized by her crown featuring the ostrich feather and solar disk. This gesture not only emphasizes the pharaoh’s reverence for Maat but also underscores his role in upholding truth and justice within the kingdom, aligning his reign with the divine principles embodied by the goddess.

Upon entering the Great Temple of Abu Simbel, visitors are immediately struck by its grandeur and the lavish praise lavished upon the pharaoh. The first chamber alone is monumental, measuring 17.50 meters in length, 15.80 meters in width, and towering over 10 meters high.

Inside, the colossal figure of Ramses II dominates the space, depicted eight times on the towering pillars that support the temple. The walls are adorned with vivid reliefs that vividly capture the exploits and military prowess of the monarch, showcasing his relentless campaign to assert dominance over Egypt’s foes.

Prominently featured are scenes depicting episodes from the Battle of Kadesh, a pivotal event in Ramses II’s reign. While these reliefs prioritize propaganda and self-glorification over historical accuracy, they are nonetheless magnificent in their portrayal. The narrative unfolds dramatically, depicting Egyptian troops caught by surprise in their camp, Ramses II’s heroic and solitary actions terrifying enemy soldiers, and the dramatic capture of enemy spies. Detailed depictions of the fortress of Kadesh, the arrival of reinforcements, fierce combat, and the victorious procession of prisoners further embellish the walls.

One particularly dazzling scene portrays the triumphant pharaoh in his war chariot, drawn by two adorned horses and accompanied by his loyal pet lion—a symbol of his royal might and divine favor. This grand tableau not only celebrates Ramses II’s military prowess but also underscores his role as Egypt’s protector and divine ruler.

Exiting the grand first chamber, the largest within the temple, visitors can access four side chapels often referred to as the Treasure Rooms. These chambers, characterized by their smaller dimensions and rougher decorations, are believed to have served as storage spaces for ceremonial objects and liturgical texts used in worship.

Moving deeper into the heart of the temple towards the sanctuary, one arrives at a room supported by four imposing pillars, symbolizing a Hypostyle Hall. Here, the reliefs diverge from depicting heroic exploits to embrace a more sublime theme. In this sacred context, Ramses II transitions from warrior king to devout ritualist, fulfilling his role as an intermediary between humanity and the divine. The walls portray the pharaoh making elaborate offerings to various gods and ceremonially purifying processional boats with the burning of incense, often accompanied by his queen, Nefertari.

Continuing further, one encounters a smaller hall flanked by two additional side chapels. The walls of this chamber are adorned with bas-reliefs depicting Ramses II presenting offerings to prominent deities such as Min-Amun-Kamutef, Horus, Thoth, Atum, Amun-Ra, and Ptah. These scenes emphasize the pharaoh’s dedication to honoring and appeasing the most significant gods, particularly those associated with kingship and the creation mythology of ancient Egypt.

Passing through the vestibule, visitors arrive at the innermost sanctum of the Great Temple of Abu Simbel—the holiest of holy places—where four deities are carved in high relief from the solid rock. These majestic figures sit side by side, emerging with imposing presence: Ptah, though somewhat deteriorated, symbolizing creation and craftsmanship; Amun-Ra, adorned with a headdress of long feathers, embodying the sun and kingship; Ramses II, depicted with the Blue Crown and identified by his royal cartouches; and Ra-Horakhty, a fusion of Ra as the sun god on the horizon and Horus crowned with the solar disk, representing divine kingship and cosmic order.

These deities hold profound significance in Egyptian cosmogony, intricately linked with monarchy and pivotal to ancient Egypt’s creation myths. Ramses II is portrayed seated among these gods, depicted with equal stature and dignity, symbolizing his divine status as a ruler. The sculptures are masterfully integrated into the rock, suggesting a unity of essence and purpose, with Ramses II depicted not merely as a mortal king but as a divine being among his pantheon.