“I’m addicted to Egypt; Egypt is everything to me.” – Jean-François Champollion

The story was penned by Jean-François Champollion, who dedicated his life to studying the history of Egypt and deciphering the Rosetta Stone—a milestone that revolutionized the understanding of Ancient Egyptian history.

To comprehend this captivating process, we must consider that in 343 BC, the last Egyptian native dynasty fell to the king of Persia, Artaxerxes III. Then, in 332 BC, Alexander the Great conquered the country, ushering in Greek cultural influence.

Consequently, Egypt became a melting pot for Greeks, Romans, Coptic Christians, Arabs… each introducing their religion, culture, and language, causing one of the most significant civilizations in our history to fade into obscurity.

Over two thousand years later, Napoleon initiated his campaign in Egypt in 1798. He arrived with an armada of approximately 40,000 men and 167 scientists, linguists, artists, and academics, tasked with studying all facets of Egyptian history and culture.

During that same year, an excavation in the town of Rosetta led Pierre François Bouchard to discover a large slab inscribed with ancient Greek, demotic, and hieroglyphic writings—the now-famous Rosetta Stone.

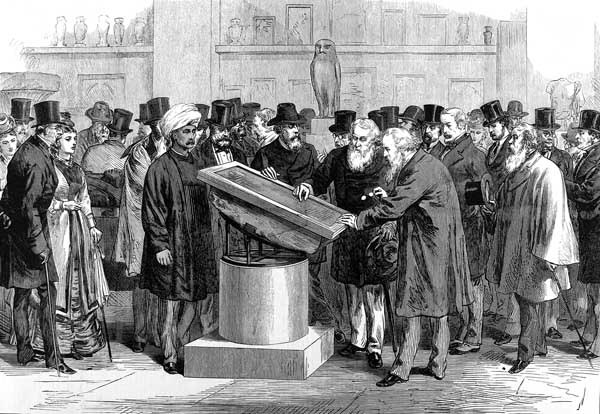

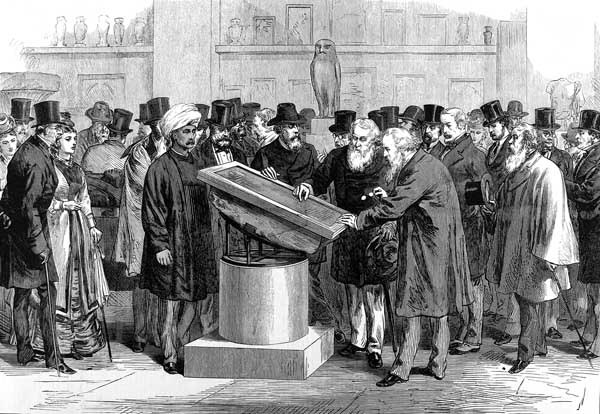

Following the Battle of the Nile and a three-year siege, the British defeated and expelled the French. As per the Capitulation of Alexandria, Egypt and all discoveries therein became property of Great Britain. Consequently, the Rosetta Stone was taken and relocated to London, where it has been exhibited in the British Museum since 1802.

On December 23, 1790, Jean-François Champollion, hailed as the father of Egyptology, was born. He received an education from his older brother, Jacques Joseph, a scholar in Ancient History and archaeology, who chose to remain in the background, supporting his brother in his studies.

Jean-François exhibited extraordinary learning abilities from a young age. By 16, he was already fluent in Greek, Latin, Arabic, Persian, Hebrew, Sanskrit, and ancient Chinese. With his brother’s guidance, he moved to Paris to study at the École Nationale de Langues Orientales, where he encountered Professor Silvestre de Sacy, one of the scholars of the Rosetta Stone.

He had to settle for mere copies for his study, as the original was in the possession of the British.

Specifically in the United Kingdom, the scientist Thomas Young, a recognized doctor and great intellectual, attempted to decipher the hieroglyphs by applying mathematics, relying on logic and numerical analysis. He counted the words in Greek and compared them with groups of symbols in the hieroglyphics.

This method seemed plausible, but he made a mistake by assuming that the hieroglyphs contained only symbols.

Years later, Champollion would demonstrate that this thesis was incorrect since the hieroglyphic characters had not only a phonetic value but also an ideographic one; it was a combination of both.

While Young presented his initial studies, Champollion was engrossed in studying the copies of the Rosetta Stone, understanding the necessity to comprehend the languages spoken in ancient Egypt to unravel its mysteries.

Champollion believed that the key lay in the study of Coptic, the language of Egyptian Christians, which directly descended from spoken Egyptian.

He learned that language from some Coptic churches that still existed in Paris.

Through the study of Coptic, he noticed that certain spellings and sounds coincided with the hieroglyphics on the Rosetta Stone. For instance, the sun was pronounced “Rae” in Coptic, and the sun god in Egypt was Ra.

On the other hand, Young had discovered, based on his comparative system, that the Rosetta Stone included the name of Ptolemy and that proper names were marked with a cartouche or cylinder.

Following Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815 and the restoration of the monarchy under Louis XVIII, the Champollion brothers were accused of conspiracy against the King.

Consequently, they lost their positions as teachers and were banished to Figeac.

During the same period, an English nobleman discovered an Egyptian obelisk on the island of Philae, adorned with various hieroglyphic inscriptions. These inscriptions were copied for study by both English and French scholars.

Upon returning from exile, Champollion dedicated himself to studying the hieroglyphics on the obelisk. Like Young, he observed a Greek inscription containing the names of Ptolemy and Cleopatra.

Among the hieroglyphic inscriptions, there were two distinct cartouches, one of which was identical to that on the Rosetta Stone. He concluded that it corresponded to Ptolemy, while the other was likely to represent Cleopatra.

Recognizing Cleopatra as a name in Modern Greek, he deduced that the hieroglyph was a translation and not an ancient representation.

However, he had yet to find the key, as the known cartouches were Greek translations, and he aimed to decipher the earlier script.

He pursued this through the study of inscriptions at the temple of Abu Simbel, containing ancient cartouches unaltered by Greeks or Romans. Using his knowledge of history, religion, and Coptic, he deciphered the words Ramses and Thutmose, unraveling the secrets of that stone.

His theory was confirmed: the Egyptian writing system integrated an ideographic and phonetic framework.

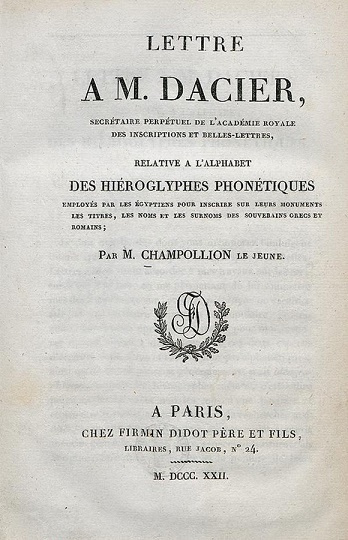

On September 27, 1822, he penned his “Letter to Dacier on the phonetic hieroglyphic alphabet,” wherein he expounded upon part of his discovery.

In France, he received congratulations, except from his former teacher Sacy, who disagreed with him. In the United Kingdom, Young accused him of stealing his ideas, although later he finally acknowledged Champollion’s achievement.

Champollion continued writing and studying hieroglyphics in the subsequent years. In 1824, he published his “Precise Hieroglyphic System of Ancient Egyptians.”

By 1826, he was appointed as the general curator of the Egyptian collection at the Louvre Museum in Paris.

In 1828, he realized his dream by leading an expedition to Egypt, confirming his discoveries and identifying the temples and funerary monuments of the Nile valley.

He passed away from a heart attack on March 4, 1832. Champollion left unfinished studies on Egyptian grammar, which were completed by his brother Jacques-Joseph.