Five thousand years ago, the rulers of Upper Egypt cast their gaze upon the kingdoms of the Nile Delta and embarked on a conquest that, according to all indications, was accomplished by Narmer, the ruler of Nekhen, who is considered the first pharaoh of a unified Egypt.

In the 3rd century BC, the Egyptian priest Manetho composed a history of Egypt in Greek for King Ptolemy II Philadelphus. Unfortunately, from this work, known as Aegyptiaca, only a few passages have been preserved, reduced to the enumeration of thirty-one dynasties along with the names of the sovereigns who constituted them and references to some significant events during their reigns.

According to Manetho, the history of dynasties commenced with Menes, acknowledged as the inaugural pharaoh of Egypt and the founder of the First Dynasty. Prior to Menes, also known as Narmer, the land of the Nile was ruled by gods and demigods.

However, modern archaeology has revealed that long before Narmer’s reign, a lengthy process of unification of the entire Egyptian territory was underway. This process was led by monarchs hailing from Upper Egypt, the southern region of the country, who are associated with what we now call “Dynasty 0.”

These monarchs ruled during the Late Predynastic or Protodynastic period, spanning from 3300 to 3100 BC. This period corresponds to the concluding phase of the culture recognized by Egyptologists as Nagada III.

Today, Nagada (known as Nubt in ancient Egyptian and Ombos in Greek) is merely a village. However, it remains a crucial archaeological site for establishing the origins of these rulers of the 0th dynasty who embarked on their campaign to conquer the northern regions of the country.

The Earliest Kingdoms

Prior to the Late Predynastic period, the various “urban” communities in Upper Egypt had clustered along the Nile, where arable land was abundant.

Peasants made use of the river’s annual flooding, combined with early artificial irrigation techniques, to enhance agricultural productivity. This allowed for the cultivation of a wider range of crops, including cereals, fruits, and vegetables, leading to a substantial population increase.

As these communities grew, they began to be governed by leaders who were universally accepted and respected. Undoubtedly, these leaders must have possessed qualities of both military prowess and effective mediation.

Between 3500 and 3300 BC, corresponding to the Nagada II or Gerzense culture, Upper Egypt featured three prominent population centers that outshone the rest: the proto-kingdoms of Hierakonpolis (known as Nekhen in Egyptian), Nagada, and Tinis-Abydos. Their expansion led to fierce competition for dominance over the entire region and control of exotic trade goods.

The rivalries among these three centers eventually culminated in the triumph of Hierakonpolis. It unified Upper Egypt under its rule and established a highly centralized government. The victorious leaders of Hierakonpolis settled in the nearby town of Tinis-Abydos, possibly with plans for future expansion northward.

It’s worth noting that the necropolises of Upper Egypt’s most influential regional centers contained burials of varying social classes during this period. The quantity and quality of funerary objects discovered in certain graves point to the emergence of a powerful elite within an increasingly hierarchical society.

While Upper Egypt achieved military unity (possibly through alliances as well as conflicts), the settlements in Lower Egypt, specifically in the Delta region, did not form a cohesive kingdom. Some prominent elites may have existed in cities like Buto (known as Pe in Egyptian) or Sais. However, in general terms, the various communities remained autonomous from one another.

Furthermore, these Lower Egyptian communities had experienced limited social changes since the Neolithic era. They were societies with minimal social disparities, as evidenced by the simplicity of the tombs unearthed in the region. These tombs typically consisted of small, ground-dug oval graves with basic funerary belongings.

Upper and Lower Egypt

Gradually, the cultures in the northern regions abandoned their traditional practices and material culture in favor of those from Upper Egypt. They adopted features like wheel-turned pottery with a red glaze and the crafting of stone vessels, which were characteristic of Nagada II.

By the onset of the Late Predynastic period, around 3300 BC, the indigenous culture of Lower Egypt had vanished, supplanted by elements from Upper Egypt. Now, the entire country was culturally united, though not politically. The political unification that would ultimately lead to the formation of the pharaonic state commenced in the south during the final phase of the Predynastic era. The expansion of Upper Egypt toward the north must have been gradual and intricate, occurring under the rule of various kings from Dynasty 0.

It is intriguing to note that in later dynastic times, starting in the 3rd millennium BC, the falcon god Horus, symbolizing order, was regarded as the protective deity of Lower Egypt, while the warrior god Set, symbolizing chaos, served as the patron deity of Upper Egypt. According to mythology, Horus and Set clashed when the latter slew Osiris, the father of Horus. Until recently, scholars interpreted this mythical conflict between Horus and Set as a reflection of the struggles between two predynastic kingdoms: one from Upper Egypt and the other from Lower Egypt.

However, contemporary understanding suggests that the unification process did not result from a confrontation between an Upper Egyptian ruler and a unified Delta. In reality, Egypt’s transformation into a territorial state resulted from the successive conquests carried out by the kings of Upper Egypt over several generations.

In this context, the concept of Egypt as a land of the Two Lands (comprising two kingdoms) lacks historical grounding. Instead, it aligns with the Egyptian notion that a whole is constituted by two opposing yet complementary parts. These two halves, Upper and Lower Egypt, had their own patron gods and emblematic symbols. Consequently, Set and the city of Hierakonpolis became the protective deity and symbolic capital of Upper Egypt, while the falcon god Horus and the city of Buto assumed the role of the protective deity and symbolic capital of Lower Egypt.

The Tomb of an Unknown King

Archaeological excavations conducted in Tinis-Abydos have unveiled the history of Egypt’s unifiers—the rulers of the 0th dynasty.

Starting from the Nagada III period, Abydos, serving as the necropolis of the city of Tinis (whose precise location remains unknown), became the final resting place for these rulers.

Their tombs have been identified in what we now recognize as Cemetery U and Cemetery B. Among the tombs, the most extensive and intricate one is the Uj tomb, associated with a leader or sovereign who lived around 3250 BC.

The discovery and excavation of this tomb took place in 1988, led by archaeologists from the German Institute in Cairo under the guidance of Egyptologist Günter Dreyer. Covering an area of 66.4 square meters, the tomb comprises twelve interconnected chambers linked by narrow vertical slots.

Despite being plundered in ancient times, archaeologists uncovered bone and ivory artifacts, including intricately carved knife handles, stone containers, a significant cache of ceramics (including plates, bread molds, and jugs containing scented oil, fats, and beer), as well as up to 400 vessels believed to have been imported from Canaan, possibly used to store wine.

Within the burial chamber, remnants of a wooden chapel and a complete ivory heqa scepter were discovered. The heqa scepter, shaped like a staff, symbolized royal authority during dynastic periods. Its presence in the tomb strongly suggests the royal status of its occupant.

Among the diverse array of funerary objects found in the Uj tomb of Abydos, the most significant for researchers may be the 150 small bone or ivory tablets engraved with the earliest hieroglyphic signs recorded in Egyptian history. These signs also appeared inscribed in black ink on ceramic vessels and represent the oldest known evidence of writing in the Nile region, possibly even the oldest writing in the world. These inscriptions confirm the indigenous origin of Egyptian writing and suggest its connection to the realm of royal funerals.

While the identity of the tomb’s occupant remains a mystery, the frequent appearance of the scorpion symbol on the ceramic vessels found there has led to the suggestion that the sovereign interred here might have been referred to as King Scorpion I. However, this is likely a symbolic name, and the prominently depicted scorpion sign may represent one of the many symbols of his power and strength rather than a literal name.

The Trials of Unification

As previously explained, the political unification of Egypt was the outcome of an extended series of military conquests in the Delta region carried out by the kings of Upper Egypt, predating the First Dynasty.

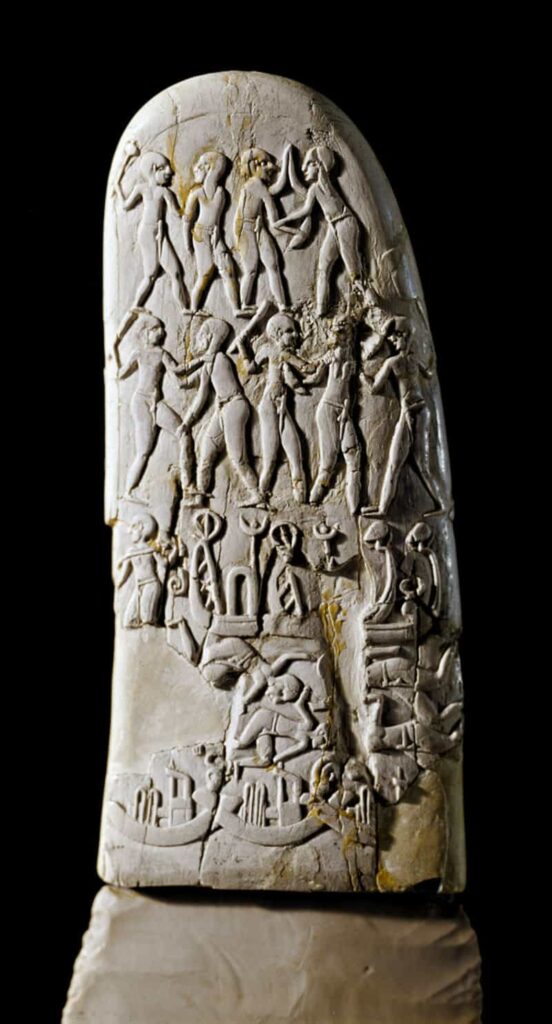

Our sole evidence of these conquests stems from the relief scenes found in the “unification documents,” which date back to the conclusion of the Predynastic era. These documents include knife handles, votive mace heads, and sizable ceremonial palettes, originally utilized as platforms for cosmetics preparation.

The Palettes of the Lion and the Bull depict the king in the guise of a lion or a bull, engaged in combat against enemies or fortified cities. These themes frequently recur in the iconography of the period and likely offer a representation of actual events.

The rulers credited with accomplishing the unification of the Two Lands are Narmer and Scorpion, though many experts propose that they might be one and the same individual.

In their respective city of origin, Hierakonpolis, a significant cult center linked to the falcon god Horus, numerous votive objects bearing these names have been unearthed. These include the renowned Palette of Narmer and the mace heads featuring Scorpion and Narmer.

It is highly probable that the scenes etched on the Narmer votive palette portray the culmination of this unification process. Narmer, recognized as the first ruler of the First Dynasty and the founder of the city of Memphis, is credited with finalizing the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt around 3100 BC.

Source: Irene Cordón i Solà-Sagalés, National Geographic