Flowy or tube dresses, skirts, tunics… For three thousand years, fashion in ancient Egypt, for both men and women, changed until it reached an unusual elegance during the New Kingdom.

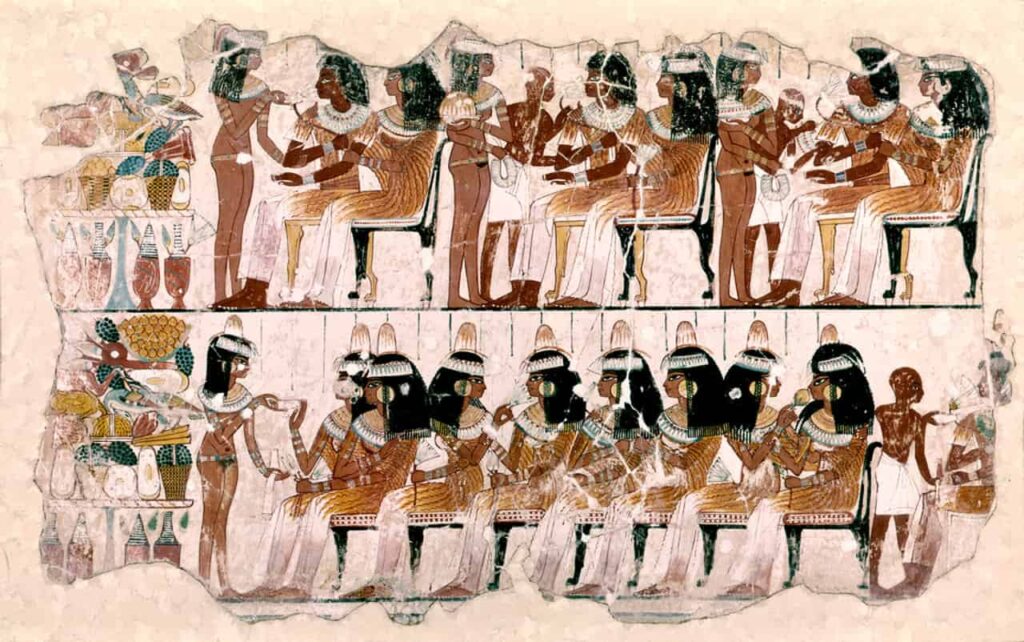

The paintings in the tombs and the bas-reliefs in the temples are excellent sources of information for learning about the evolution of ancient Egyptian clothing.

In them, it is verified that the lightness of the dresses was almost obligatory (Egypt is a warm country); transparencies and nudity lacked the erotic connotations to which we Westerners associate them.

In fact, until the Macedonian conquest, the textile fiber used in the Nile Valley was linen. Its cultivation and manufacture were almost always a state monopoly and were offered in different qualities. The supreme one, due to its transparency and delicate weave, was the royal linen, with which, as its name indicates, kings and nobles dressed.

Uniforms

The dresses, like their jewelry accessories, were clear indicators of the social category of the wearer. But also, as a uniform, they differentiated positions, professions, and trades.

The viziers, for example, wore loose white tunics that reached mid-calf from chest height. Narrow straps, perhaps made of metal due to their strange curvature, held this peculiar garment in place.

The soldiers’ attire allowed them to be easily recognized by a large triangle superimposed on the front part of their skirt.

In reality, the ancient Egyptians felt a strong attachment to traditions, and their orthodox behavior in all aspects of daily life meant that their clothing did not change noticeably. But it was inevitable that over almost three millennia there would be some formal changes.

Belts and Suspenders

Female dresses from the Old and Middle Kingdom are easily recognizable. Simple in cut, they consisted of a single tight-fitting garment held by two wide straps that, covering the chest, reached almost to the ankles.

Men, especially peasants and workers, wore a simple skirt above the knees, the shenti, which was the masculine garment par excellence throughout the pharaonic period. Made from a piece of linen, it was crossed and tied at the waist or cinched with a belt.

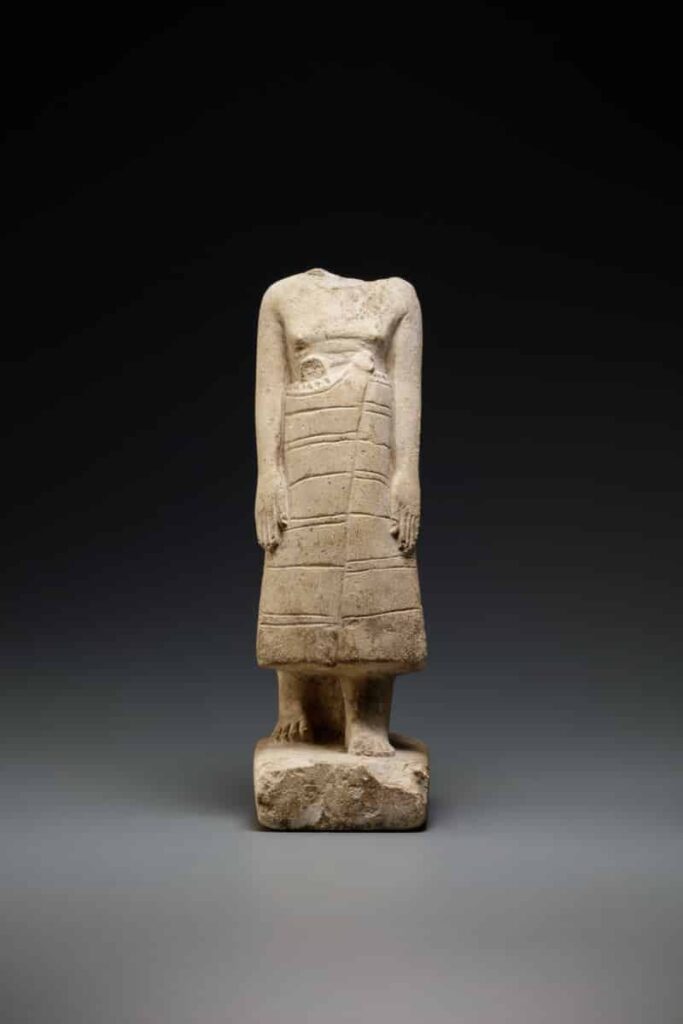

High officials also appear with this skirt, although, little by little, the upper classes tended to lengthen it until it covered their knees. A luxury variant consisted of a long skirt whose front part, starting from the waist, extended forward, widening until it reached about fifty centimeters at the bottom. Seen from the front, it appears, in the statues, as an isosceles triangle, while from the side it resembles an inverted prow.

In the New Kingdom, the most substantial change in fashion occurs. High officials wear a transparent calf-length tunic over their skirts. The wide sleeves, often pleated, give the general image an unusual elegance.

There are feminine garments that can seem even more daring. At the funeral banquets in the Theban tombs, the ladies of high society wear a dress that, held by a single strap, leaves one breast exposed. The young servants who serve them are completely naked, wearing only a narrow belt.

But there were still exceptions: the wives of the workers of the royal necropolis devised a truly revolutionary, elegant, cheap, and chaste dress: a rectangular piece of linen, finished on one side by a fringe, almost two meters long by one meter wide. Extended on the back, the vertical edges folded forward passing in front of the arms until they crossed, hugging the body. The two upper points folded over the shoulders, crossing at chest level where they were fixed with a simple knot. A linen band, similar to a shawl, girdled the dress below the breast.

Source: Fernando Estrada, National Geographic