The Libyan Palette, also known as the Libyan Booty Palette or the Libyan Tribute Palette, offers a glimpse into ancient Egyptian art and historical narratives.

Carved from schist during the Naqada III or Protodynastic Period (circa 3200 to 3000 BC), it is housed in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Although only the lower section survives, its intricate decoration on one face vividly portrays significant events.

Libyan Palette, Side 1

The surviving portion reveals four registers of decoration. The uppermost register features a line of bulls facing right, their muscular forms depicted with exaggerated tension, heads lowered as if ready to charge. Each bull is meticulously detailed, their powerful presence contrasting with the scenes below.

The second register showcases a procession of donkeys, less detailed but still conveying movement and purpose. The third register displays rams, with the last ram cleverly depicted smaller and with its head turned backward to fit the available space.

At the bottom of the palette, the final register presents a row of eight trees, likely olive trees, arranged in a pattern. The name “Libyan Palette” derives from hieroglyphs at the top right, depicting a piece of land with a throwing stick, associated with the Libyan regions (Tehenu).

Interpreted as a commemoration of victory over Libyan peoples, the palette’s decoration symbolizes the spoils of war, capturing the essence of ancient Egyptian triumphs and territorial expansion.

The significance of olives depicted on the palette raises questions about early cultivation practices, hinting at the cultural and agricultural exchanges of the time.

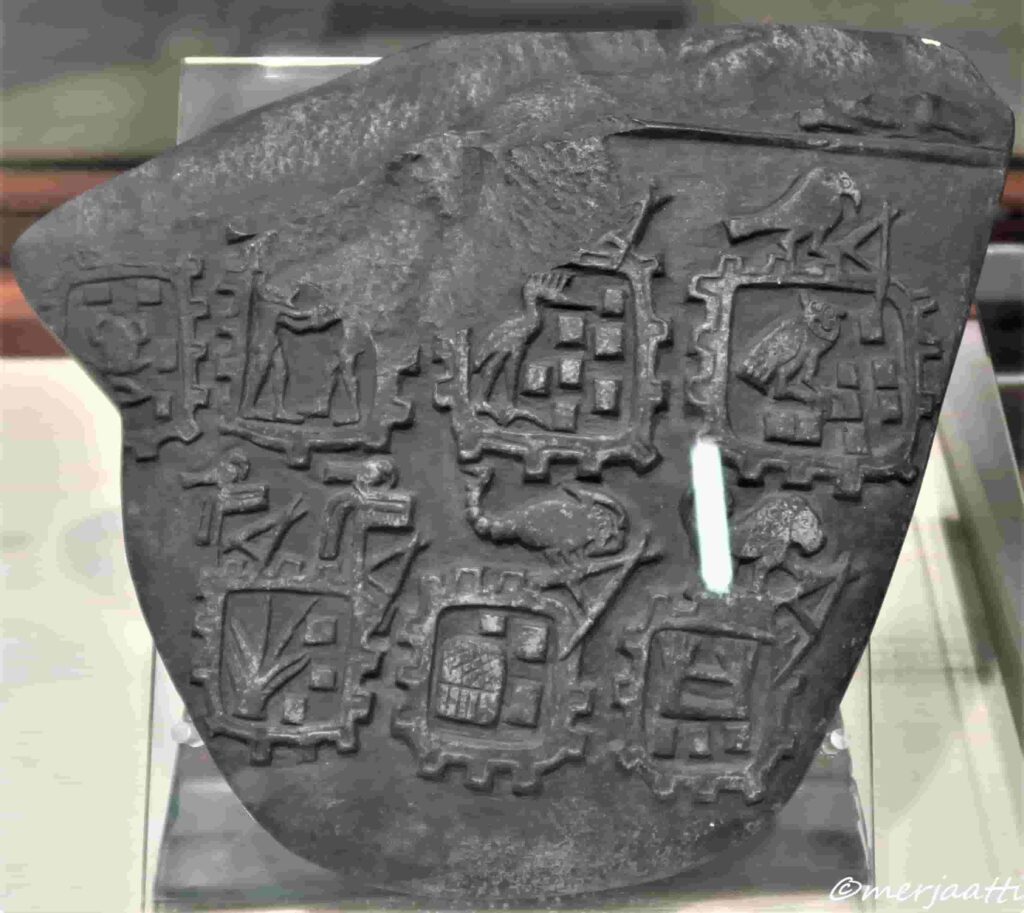

Libyan Palette, side 2

The reverse side of the Libyan Palette presents a unique blend of pictorial representation and hieroglyphic symbolism, offering insights into ancient Egyptian narratives and cultural practices. Positioned below the baseline of another scene, now partially lost, it depicts a complex tableau that has sparked scholarly debate and interpretation.

Central to this scene are several prominent elements: a falcon, a lion, a scorpion, and two falcons on a banner, each holding a mattock, situated atop the walls of seven cities.

The cities are delineated by buttressed walls, within which are depicted squares representing buildings and hieroglyphs. These enclosed hieroglyphs have been interpreted as identifying the names of the settlements, suggesting a scene depicting the founding of a series of cities by a ruler symbolized by the animals.

However, interpretations vary among scholars. Some propose that the animals may represent royal armies or symbols, signifying conquest or territorial expansion.

Alternatively, it has been suggested that the scene portrays destruction, with the animals or animal standards possibly representing royal names or titles associated with military campaigns.