The Great Sphinx stands as one of ancient Egypt’s most iconic and awe-inspiring monuments. Positioned majestically in front of the pyramids of Giza, this monumental stone figure, with its solemn visage and leonine body, captures the imagination and wonder of all who behold it.

Early Western travelers who encountered the Sphinx were understandably perplexed by its immense size and striking appearance. Some found its grandeur serene and beautiful, while others perceived it with a mix of apprehension and awe. This blend of emotions is aptly reflected in the Arabic name for the Sphinx: “Abu el-Hol,” meaning “the Father of Terror.”

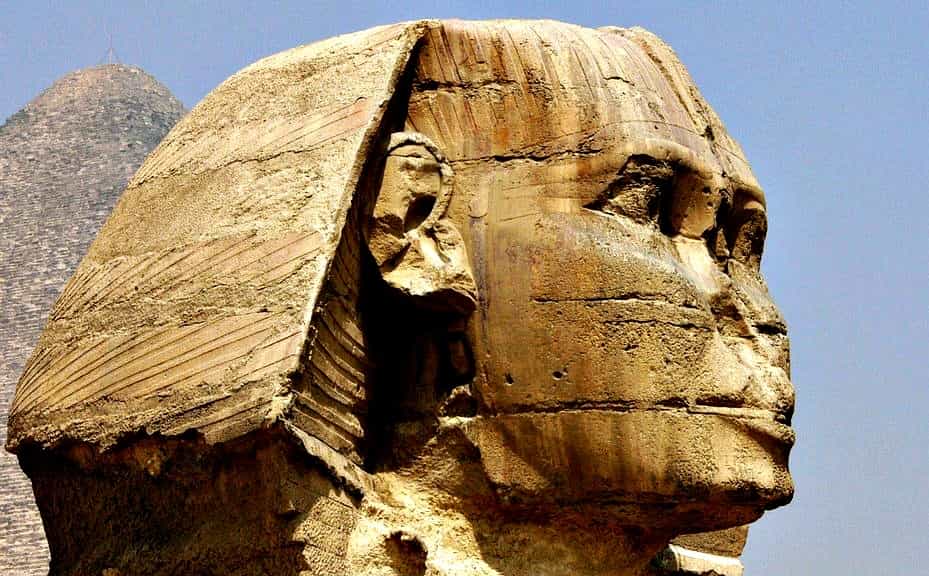

Whether captivated by its calm expression or unsettled by its imposing presence, one question frequently arises: what happened to the Sphinx’s nose? The missing nose is particularly noticeable given the relatively well-preserved condition of the rest of the face.

During the Napoleonic conquest of Egypt between 1798 and 1801, it was rumored that French troops damaged the nose of the Great Sphinx. Allegedly, they either fired cannon shots at it or used it for target practice.

This theory suggests a surprising contradiction, as the same troops who marveled at the splendor of ancient Thebes and accompanied scholars who would publish “La Description de l’Égypte,” the seminal work of Egyptology, would seem unlikely to wantonly damage such a significant artifact.

However, historical evidence indicates that the Sphinx’s nose was already missing before Napoleon’s arrival in Egypt. This fact challenges the narrative that French soldiers were responsible for the damage, pointing instead to an earlier cause.

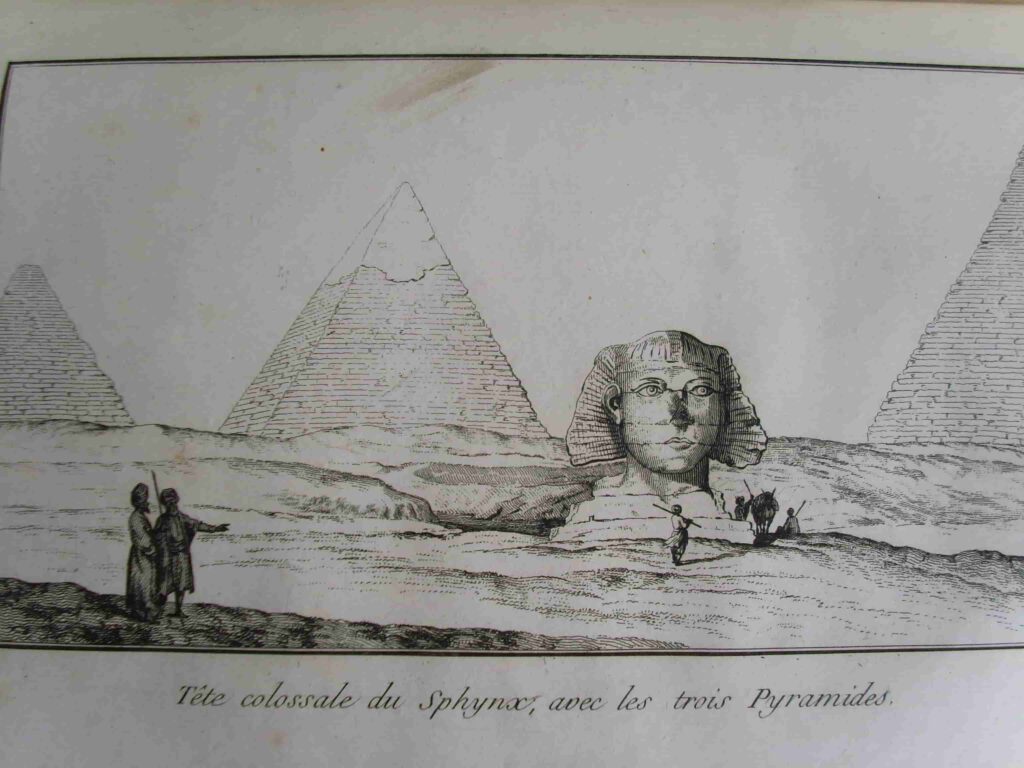

While the drawings and engravings created by travelers to Egypt in past centuries often reflect idealizations, interpretations, or reinventions of what they observed, some aimed for accuracy and authenticity, resisting the urge to indulge in imaginative embellishments.

One such example is an engraving by Frederik Ludwik Norden, which clearly shows the Great Sphinx of Giza without a nose as early as 1737. This evidence indicates that the Sphinx’s nose was missing at least 61 years before Napoleon’s forces arrived in Egypt.

The damage to the Sphinx’s nose appears to date back even further. The 15th-century Arab historian al-Maqrizi provides an account of the iconoclast and Sufi leader Muhammad Sa’im al-Dahr, who defaced the Sphinx in 1378.

According to al-Maqrizi, Sa’im al-Dahr was outraged by the local Egyptian peasants’ superstitions and the offerings they made to the Sphinx in hopes of securing bountiful floods and good harvests.

In response, Sa’im al-Dahr damaged the monument, breaking off its nose and also harming its ears. His acts were later deemed vandalism, leading to his execution by hanging.

The Great Sphinx of Giza, an ancient and captivating monument, has endured millennia of exposure to the elements. While its body has been somewhat shielded by being buried in sand over the centuries, its head has faced relentless natural forces.

The nose, being particularly vulnerable, has suffered more than other parts of the statue, enduring the harsh desert winds, abrasive sand, and temperature fluctuations.

In recent times, pollution and harmful underground water leaks have further threatened the Sphinx’s structural integrity. Despite these challenges, efforts continue to preserve this magnificent monument for the enjoyment and wonder of future generations.