In certain parts of the world, even today, you can still witness groups of women who, despite not being part of the deceased’s family, publicly express profound sadness and grief. These women are the mourners, a profession with ancient origins that was exclusively female in ancient Egypt and passed down from mothers to daughters.

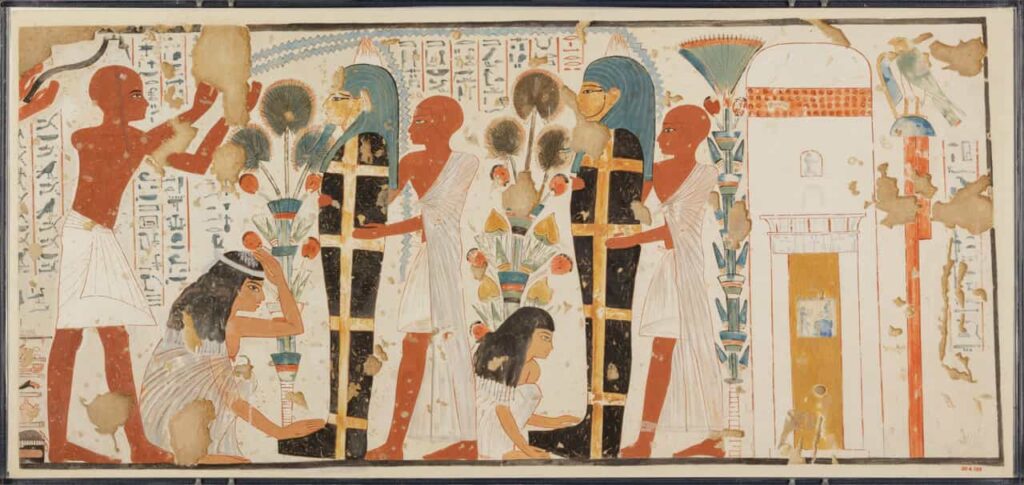

The funeral procession is approaching its final destination. The individuals carrying offerings transport all the necessary objects, such as furniture, food, and drink, to ensure the deceased’s soul can enjoy a pleasant afterlife.

The family of the deceased proceeds with great sorrow. The young widower is engulfed in deep sadness. They had only been married for three years, not even having had the opportunity to have children. However, he cannot display his pain openly, aware of societal expectations. If he were a woman, he could kneel at the foot of the sarcophagus and openly lament without shame.

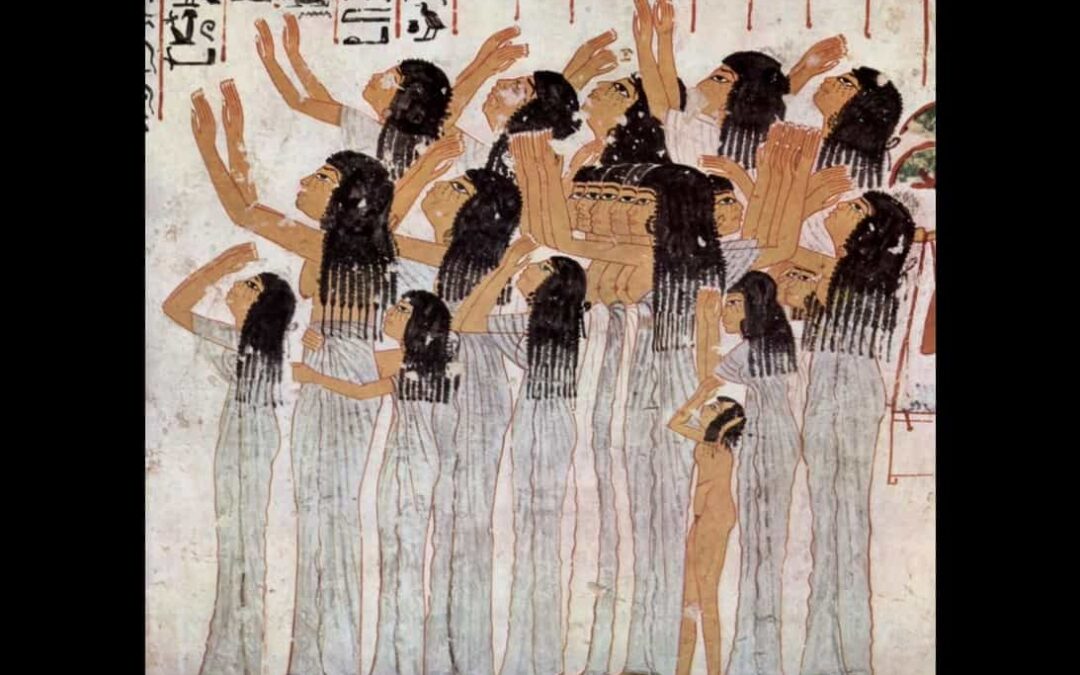

In contrast, a group of women behind him openly expresses their anguish. They scream, cry, and vigorously shake their heads back and forth, causing their long hair to sway, sometimes becoming entangled and soiled with ashes. The young widower finds solace in this display. At least his pain can be mirrored by the heart-wrenching cries of these women…

Crying in Exchange for Compensation

But who were these mourners who accompanied the funeral processions? Well, they were known as mourners, professionals in the art of mourning and grief who performed this role for payment. In ancient Egypt, it was an exclusively female profession.

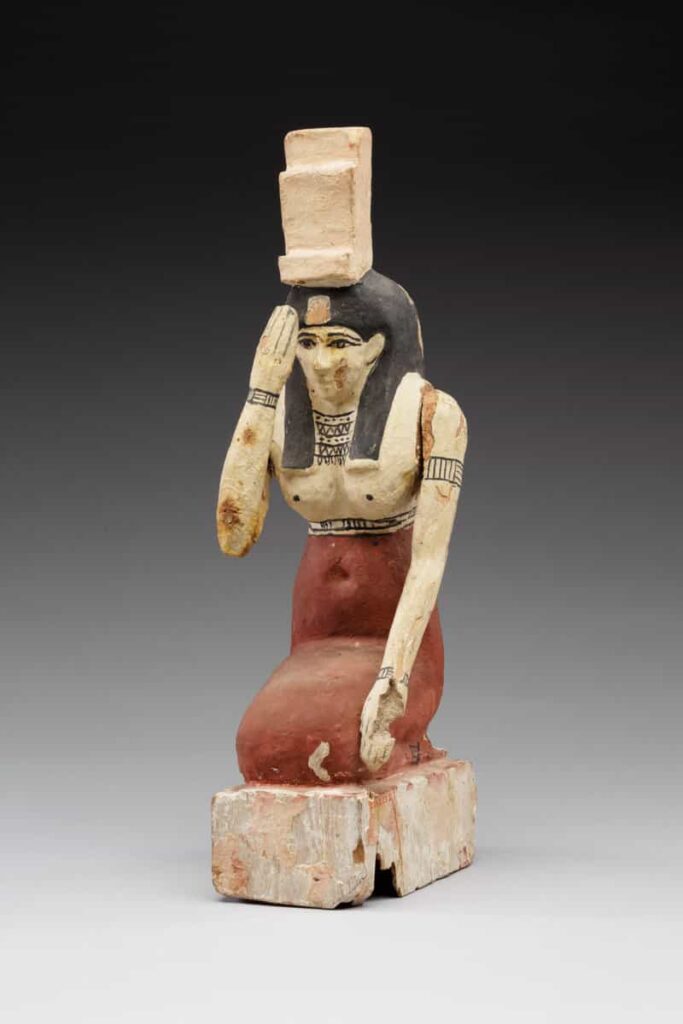

These groups of women, singers dedicated to the goddess Hathor, were hired by the deceased’s relatives to display intense grief that they were not permitted to express publicly.

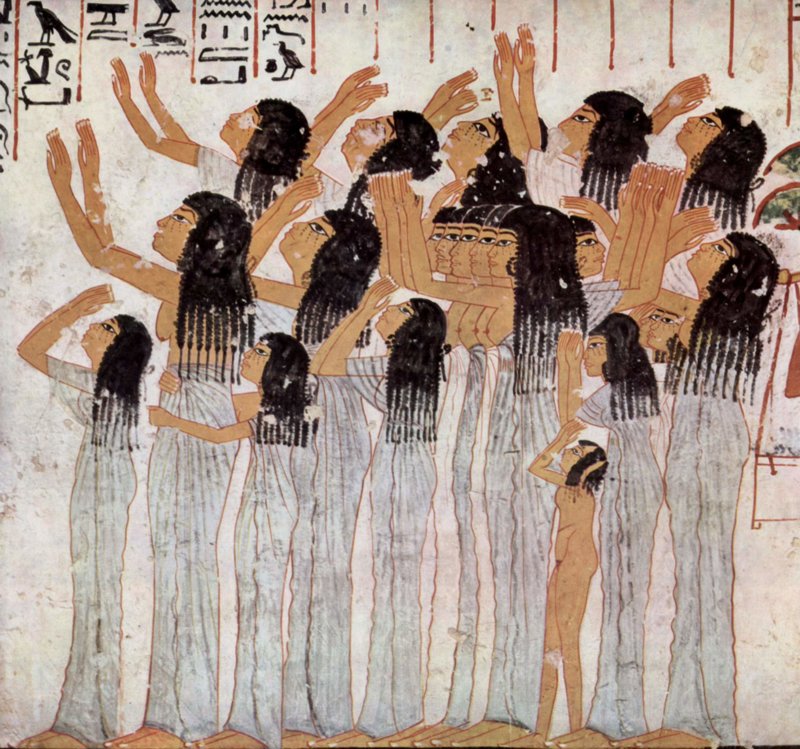

The mourners, attired in white or bluish-gray linen dresses, followed behind the procession with their chests bare, casting dust or ashes upon their heads. They raised their arms towards the sky or pointed towards the ground with their palms, occasionally covering their tear-streaked faces.

As skilled mourning professionals, these women possessed a vast repertoire of texts and songs, which they recited during their duties. “You, who once had a large family, now reside in solitude. He who used to walk freely is now motionless, swathed in bandages,” read one text. “Offer water to those who desire a drink,” they added in reference to the deceased.

In addition to mourning the loss of an individual, these professionals were also hired to deliver eulogies. Although not an essential part of the funeral ritual, their presence added to its grandeur.

Consequently, the size of mourner groups varied depending on the importance of the deceased, and often they were accompanied by their daughters when fulfilling their duties.

This can be observed in a painting found in the tomb of the vizier Ramose in Thebes, where an artist depicted a group of mourners in a sorrowful stance, with raised arms in a gesture of lamentation, accompanied by young girls, including a naked young girl.

Indeed, like most professions in ancient Egypt, this role was passed down from mothers to daughters, allowing girls to begin following in their parents’ footsteps from a very young age.