Ahmose-Meritamun: Queen of Egypt during the early Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt. She was the sister and the Great Royal Wife of the second king of this dynasty, Amenhotep I and, therefore, daughter of Pharaoh Ahmose I and Queen Ahmose-Nefertari.

It seems that she had some older sisters, but none of them would marry their brother because they died before he assumed the throne.

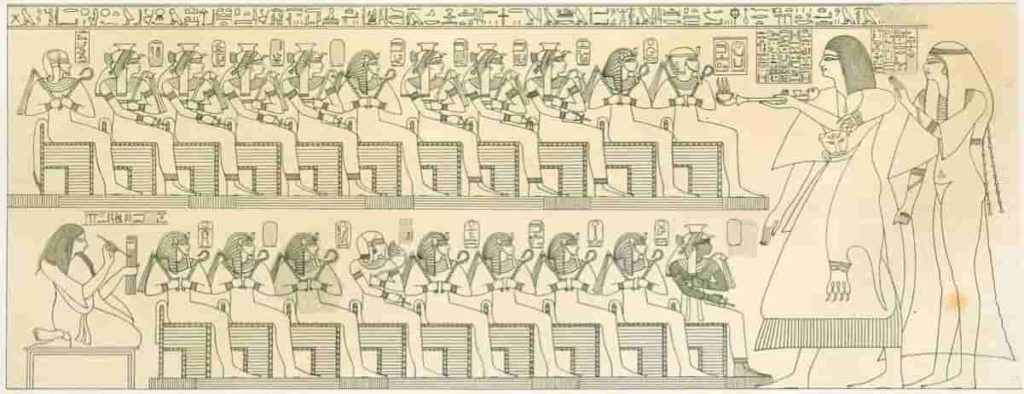

Ahmose-Meritamun held the position of God’s wife and was the eternal and silent companion of her husband, but, unfortunately for her, she could not bring into the world any known offspring that reached adulthood and could succeed their father.

Perhaps this is why Amenhotep “punished” his wife for not appearing in so many historical documents, surprising Egyptologists that he is always with his mother the great queen Ahmose-Nefertari, instead of his wife.

For this reason, on the death of Amenhotep I, Thutmose I took the throne, which could either be a son of the deceased with a secondary wife or descend by another means from the Ahmose family.

When Queen Ahmose-Meritamun died (we do not know if it was before or after her husband), she was buried in a tomb excavated at the foot of the Deir el Bahari cliff, named TT358.

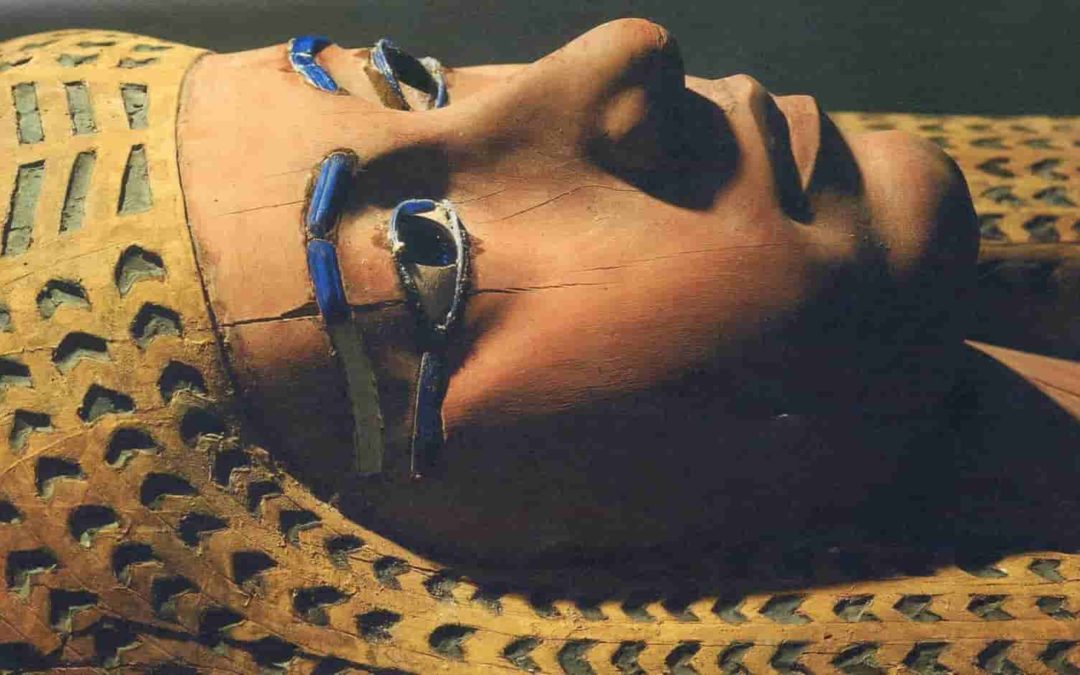

It was there where she was found at the beginning of the 20th century, her double polychrome wooden sarcophagus being one of the most beautiful in that forgotten place.

As much as many sources affirm that Amenhotep I was not married to Ahmose-Meritamun, and that his great royal wife was a certain Ahhotep II, this information is uncertain, since there is no Ahhotep who lived at that time in the royal family.

Ahmose-Meritamun was the second queen of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Giovanni Belzoni, when he was working in Karnak, in 1817, discovered a fragment with the upper part of a large statue of Ahmose-Meritamun with a wig, in limestone. The statue is kept in the British Museum.

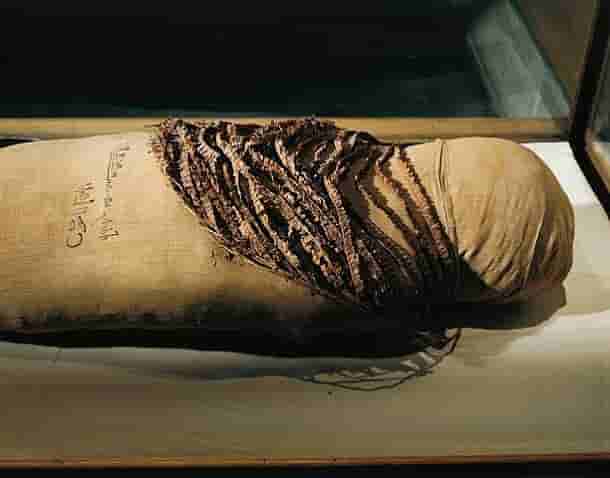

Her mummy was found in 1930, in a tomb cataloged as TT358, during the excavations of an American mission led by archaeologist Herbert Eustis Winlock.

Her burial was considerably simple, with two wooden coffins and a paper wrapper.

It turns out that her tomb was opened by looters, but her body returned to the resting place after priests found it and buried it again. Contemporary studies have revealed that the woman died young after being the victim of bone diseases.

Currently, her sarcophagus found in the Egyptian Museum, an important academic institution in Cairo, is more than 3 meters long, made of cedar boards made with mastery and uniformity.

It was also sculpted and underwent conservation and prestige procedures, such as the inlay of its eyes and eyebrows on the glass.

The handmade work on the outside created a unique texture, painted blue in the process of joining the boards and, furthermore, characterized by gold, in a determination of the queen’s prestige and wealth. The inner coffin was also covered with gold and carefully preserved.