During the New Kingdom, prominent individuals in Thebes, such as courtiers, officials, and nobles, sought to emulate the pharaohs by constructing elaborate tombs with the aim of ensuring a joyful journey into the afterlife.

Starting from the 18th Dynasty (circa 16th to 14th centuries BC), Thebes emerged as the capital of a thriving Egyptian Empire. With strong dynastic roots in the city, pharaohs chose to be interred there, cementing Thebes’ significance as a sacred site. Their eternal resting place was established on the west bank of the Nile—the symbolic land of the dead—where the renowned Valley of the Kings was nestled in a secluded wadi.

Inspired by the pharaohs’ example, many high-ranking individuals aspired to be buried near the royal necropolis to maintain the presence of their rulers even in the afterlife.

Over time, a collection of nearby burial grounds took shape, including Qurnet Murai, Sheikh Abd el-Gurna, Asasif, Khoha, and Dra Abu el-Naga. These interconnected necropolises transformed the western Theban slopes into an intricate network of tombs, ranging from modest burials to grandiose mausoleums.

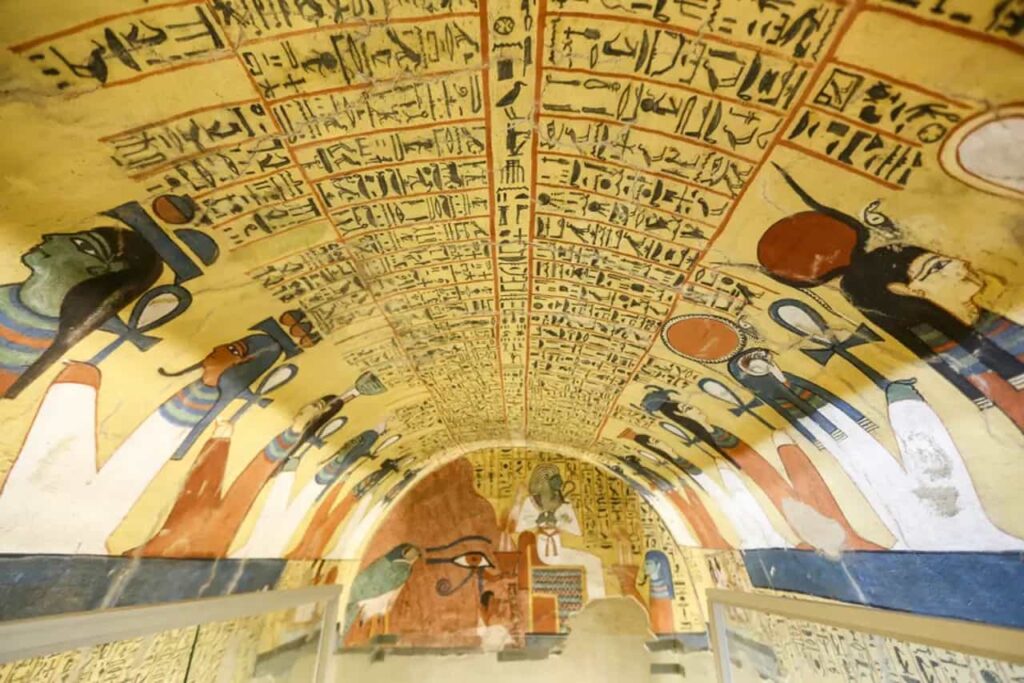

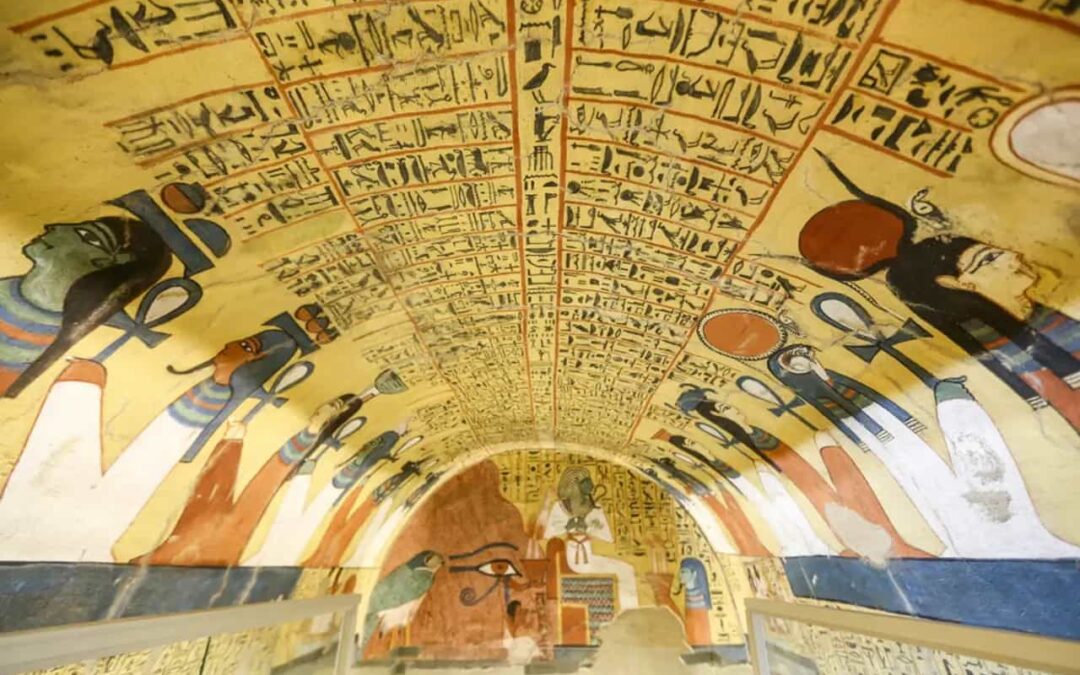

The tombs of Thebes, known as hypogea, are rock-cut structures adorned with intricate reliefs and vivid mural paintings that stand among the finest achievements of ancient Egyptian art. With hundreds of these tombs scattered across the landscape, it would be impossible to visit them all.

However, a glimpse into their artistic splendor can be gained by exploring a few of the most famous ones, such as the tomb of Rekhmire, a vizier who served under Thutmose III and Amenhotep II; the tomb of Sennedjem, a craftsman who worked on decorating the Valley of the Kings; or the tomb of Djehuty, a high official during Hatshepsut’s reign, noted for its exceptional relief work.

While hypogea existed in the Old Kingdom, their construction on the western slopes of Thebes truly flourished during the Middle Kingdom. This period saw the development of a distinctive type of royal burial known as the saff tomb.

The structure featured a large courtyard carved into the hillside, bordered by stone walls. At the back of the courtyard lay the tomb itself, characterized by rows of pillars hewn from the rock, giving the façade an appearance of multiple doorways—fittingly, the Arabic word “saff” means “rows” or “many doors.”

Beyond these pillars was a simple corridor, usually undecorated, leading to a series of small chambers, one of which contained the burial shaft. This style served as a precursor to the inverted T-shaped tombs that became the standard design during the New Kingdom.

Most of the accessible hypogea in the western hills of Thebes today follow this pattern, though variations on the basic model can also be found.

The Kingdom of the Dead

The tombs of New Kingdom nobles in Thebes were built with a fairly consistent layout. Each tomb typically began with an outer courtyard, the size of which varied but was generally as wide as the façade itself. In this courtyard, niches for statues were often present, along with paired steles—one inscribed with the deceased’s biography and the other featuring a religious hymn.

Upon entering the tomb, visitors would encounter a transverse corridor running parallel to the façade. At the center of this corridor, aligned with the entrance, a second passage led directly to the funerary chapel.

In the funerary chapel, on the back wall opposite the entrance, stood a statue of the deceased, frequently accompanied by figures of close family members, such as parents or a spouse. Despite common misconceptions, this chamber was not intended to house the tomb owner’s mummified remains.

Instead, a careful examination of the floor would reveal a rectangular pit, just large enough to accommodate a coffin. This served as the entrance to the actual burial chamber, which could extend deep underground, sometimes more than ten meters.

At the bottom of the pit, a room carved into one of the walls contained the sarcophagus holding the mortal remains. Although decorated burial chambers do exist, they are relatively rare. In contrast, the other walls throughout the tomb were usually adorned with richly painted scenes or detailed reliefs, covering nearly every surface.

The layout of the tombs was structured into three distinct levels, each representing the ancient Egyptians’ conception of the universe. The lowest level, situated at the base of the burial shaft, was the burial chamber itself, symbolizing the Duat—the underworld where Osiris reigned as the god of the dead. This level was considered the realm of the deceased, embodying the world beyond life.

The middle level served as a transitional space between the living and the dead. Accessible to all, not just the deceased’s family, this area allowed visitors to pay their respects. It was also the setting for the funerary rituals and ceremonies performed on the day of burial, which were essential for ensuring the deceased’s successful transition to a vibrant existence in the afterlife.

The uppermost level featured a superstructure situated above the tomb’s façade. In the later New Kingdom, this structure often took the form of a small brick pyramid. The pyramid, a symbol associated with the sun, connected this level to the divine realm of Amun-Ra, representing the world of the gods.

Source: José Miguel Parra, National Geographic