The study of ancient artifacts holds many untold secrets about the civilizations that created them. One such artifact is a stone fragment located in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of Ancient Egyptian Art. The scientific investigation of this object has shed light on a long-standing debate among experts in the field of ancient Egyptian technology: the use of high-performance abrasives.

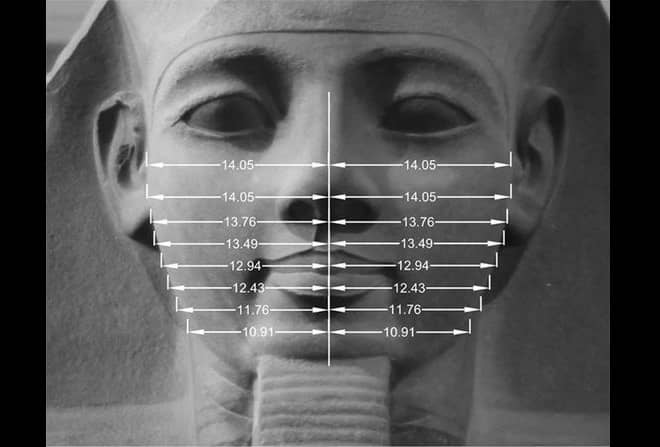

For thousands of years, the skilled artisans of Ancient Egypt excelled in extracting and shaping various types of stones, including both soft and hard stones, using a range of tools and techniques.

Abrasives were a crucial component in this process, and saws and core drills relied on particulate abrasives. The finishing of sculptures and architectural elements was achieved by combining rubbing stones and abrasive slurries.

The composition of the abrasives used has been a topic of much discussion, particularly in relation to the working of hard stones such as granite, diorite, and quartzite.

The question remains whether these stones were shaped and polished with only quartz-based abrasives or if the ancient Egyptian craftsmen had access to harder materials such as corundum and emery. These mineral mixtures are known to have been used by artisans in the ancient Mediterranean and Near East, but there is limited evidence of their use in Ancient Egypt.

The debate on the type of abrasives used by the skilled artisans of Ancient Egypt has been ongoing among scholars for some time. While some have proposed the use of emery abrasive powder, the lack of direct evidence in Egypt and the absence of known sources of emery in the region, along with the presence of quartz sand in ancient drill holes, has led others to reject this theory.

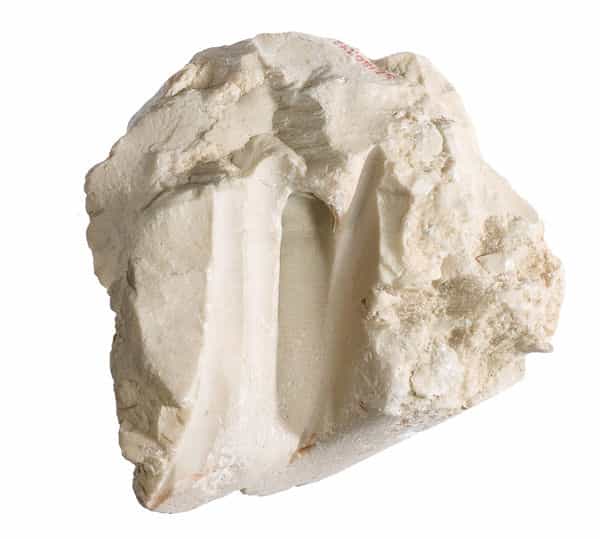

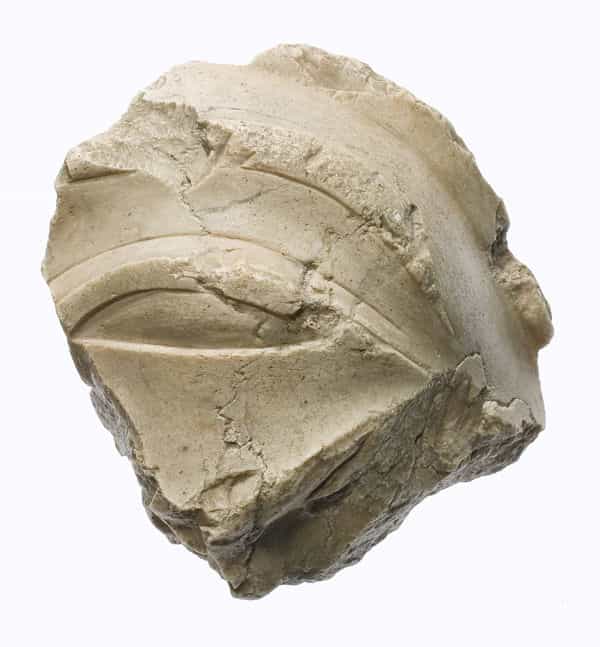

A small fragment of limestone, discovered in the Met’s collection and excavated from a pit outside the Great Temple of the Aten in Amarna in 1891-92, holds the key to solving this debate.

The fragment, measuring only 8 cm in height and 7 cm in width, may appear unimpressive with its shapeless form and unrecognizable features, but it contains information that is vital to uncovering the mysteries of ancient Egyptian technology.

The fragment reveals several signs of what appear to be drill holes, each cut at slightly different angles. The main drill hole is approximately 1 cm in diameter and contains a protruding stump, the result of a broken drill core, surrounded by a lightly consolidated powder that is believed to be the remains of an ancient abrasive. At first glance, the material appears to be a fine-grained, whitish powder with dark, slightly coarser grains, and a light green stain.

With the help of scientific techniques such as scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), the material was identified as a mixture of predominantly angular grains of corundum (aluminum oxide) with jagged edges, and a few other minerals including quartz, rutile, feldspar, apatite, ilmenite, augite, biotite, and chromite.

These minerals are smaller in size and highly angular in shape. The presence of very fine particles of calcite surrounding the larger particles suggests that the remains of the indurated limestone drilled were also present. The light green color is due to the presence of corroded bronze and green copper corrosion products dispersed among the minerals.

The recent discovery of corundum particles in the ancient Egyptian limestone fragment from the Met’s collection has shed new light on the advanced technology used by the craftsmen of that era. The high abrasive efficiency conveyed by the corundum suggests that it was intentionally used in the drilling process of the hard limestone, leading researchers to believe that a bronze tubular drill was employed alongside a corundum-rich abrasive mixture.

While the use of corundum is a significant breakthrough, the origin of the abrasive remains a mystery. The mineral composition found in the Amarna fragment differs from the commonly used emery and raises questions about its source and manufacturing process.

One possibility is that the abrasive was a byproduct of the mining of gem-sized crystals, with a technical and economic value of its own. In Egypt, the only known corundum deposit of this type is located in Hafafit, located in the southern part of the Eastern Desert.

Further investigation is needed to verify the consistency of these findings, including analysis of new samples from other worked objects and comparison with corundum-bearing deposits, both the historical emery deposits and the lesser-known source in Hafafit.

The pursuit of knowledge about the advanced technology used by the ancient Egyptians continues, with each new discovery bringing us closer to unlocking the secrets of their remarkable civilization.

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Anna Serotta, Associate Conservator, Department of Objects Conservation; and Federico Carò, Research Scientist, Department of Scientific Research