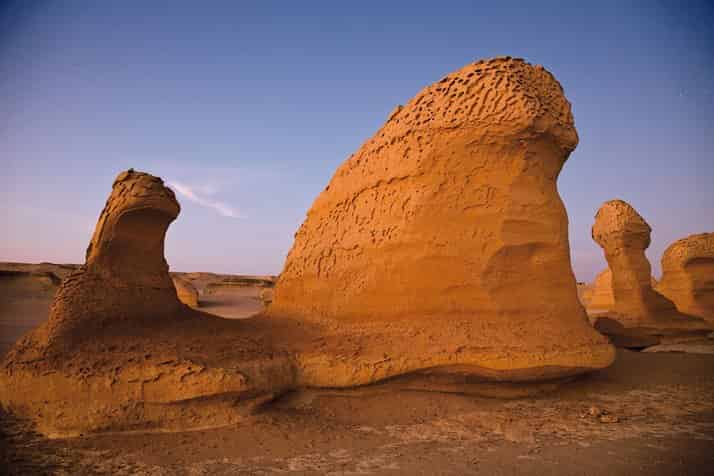

Wadi Al-Hitan or Valley of the Whales is a region of the Governorate of Faiyum, in the western desert of Egypt that contains important fossil remains of the suborder Archaeocetos (the ancestors of modern cetaceans). It was included in the list of “World Heritage” the UNESCO in July 2005.

An Egyptian desert, once an ocean, holds the secret of one of evolution’s most remarkable transformations.

Thirty-seven million years ago, in the waters of the ancient Sea of Tethys, a sinuous beast 15 meters long, with enormous jaws and sharp teeth, died and sank to the bottom of the sea.

Over the millennia, a blanket of sediment built up on their bones. The sea receded, and when the ancient seabed turned into desert, the wind began to wear away the sandstone and clay deposited on the bones. Little by little the world changed.

The movements of the earth’s crust pushed India against Asia, and the Himalayas were formed. The pharaohs built the pyramids. Rome rose and fell. And all the while the wind continued its patient digging.

Then one day Philip Gingerich came to finish the job. One afternoon, Gingerich, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Michigan, had sprawled full length next to the spine of a beast called Basilosaurus, in a place in the Egyptian desert known as Wadi Hitan.

The sand around them was strewn with fossils of shark teeth, sea urchin quills, and giant catfish bones. “I spend so much time surrounded by these aquatic creatures that, shortly after being here, I live in their world,” he said, brushing a vertebra the size of a log.

When I look at this desert, I see the ocean. ” Gingerich was looking for a key piece of the animal’s anatomy, and he was in a hurry. It was getting dark and he had to get back to camp before his colleagues began to worry.

He continued up the spine, toward the tail, tapping around each vertebra with the handle of the brush. Finally he stopped and put the instrument on the ground. “Here is the treasure,” he said.

He delicately brushed the sand away with his fingers, revealing a thin cylindrical bone just 8 inches long. “You don’t see whale feet every day,” he added, raising the bone with both hands in an attitude of respectful reverence.

Basilosaurus was indeed a whale, but a whale with two delicate hind legs, the size of a three-year-old girl’s legs, protruding from the flanks.

Those captivating limbs, perfectly formed but useless (at least for walking), are a crucial clue to understanding how today’s whales, those supreme swimming machines, descend from land mammals that once walked on all fours.

Gingerich has devoted much of his career to explaining this metamorphosis, probably the most radical in the animal kingdom.

“Whole specimens like that Basilosaurus are the Rosetta Stone,” Gingerich told me back at camp.

In Wadi Hitan (“valley of the whales”), such Rosetta stones abound. In the last 27 years, Gingerich and his colleagues have located the remains of more than a thousand whales, and there are many more to discover.

When we arrived at the camp, we met several members of Gingerich’s team who had just returned from their fieldwork day. Mohammed Sameh, chief ranger for the Wadi Hitan protected area, had been searching for whales a little further east and reported several new piles of bones, fresh clues to unraveling one of the great riddles of natural history.

Source: National Geographic

Photos: Richard Barnes