In 1858, Alexander Henry Rhind, a Scottish lawyer and Egyptologist, found himself back in Egypt once more. One day, while wandering through the shops and stalls in Luxor, Rhind stumbled upon a particularly intriguing discovery.

It was a lengthy papyrus, measuring nearly 6 meters in length and 33 centimeters in width. According to the vendors, this artifact had been unearthed from a room near the Ramesseum, the grand funerary complex dedicated to the famous Ramses II.

Five years later, the Egyptologist passed away, and much of his belongings, including the papyrus, were sold to the British Museum in 1865. Subsequently, it was revealed that a fragment housed in the Brooklyn Museum actually belonged to the same preserved papyrus in London.

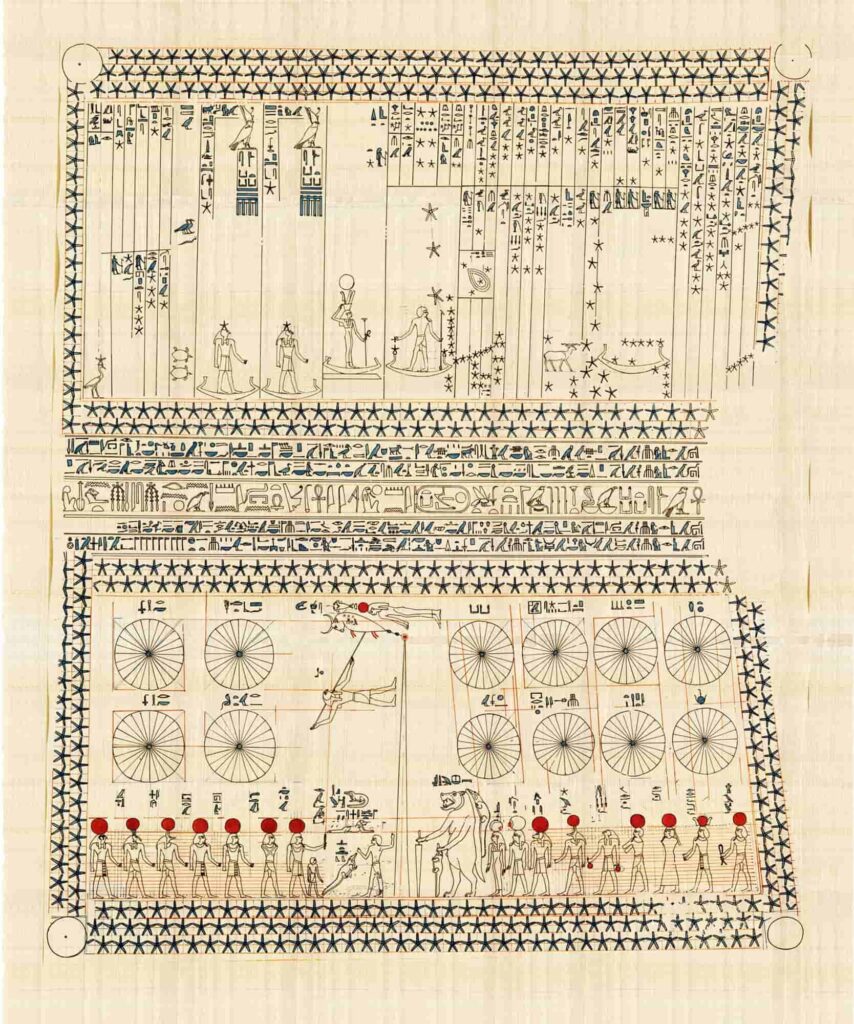

Penned in hieratic script—a simplified form of hieroglyphics utilized for administrative and commercial purposes—the papyrus commenced with the intriguing declaration: “Exact calculation to gain knowledge of all existing things and all dark secrets and mysteries.”

While this statement may evoke the mystique surrounding ancient Egypt, the contents of the manuscript delve into a realm more grounded in practicality. It is, in essence, a treatise on mathematics.

Dubbed the Rhind Papyrus, this ancient document stands as a cornerstone in our understanding of Egyptian mathematical prowess. Within its ancient fibers lie insights into fundamental arithmetic, fractions, methods for calculating areas and volumes, progressions, proportional distributions, rules of three, linear equations, and even rudimentary trigonometry.

Ancient Egyptian Mathematics

The Ahmes Papyrus, named after its scribe Ahmes, dates back to approximately 1650 BC and draws from writings that are 200 years older, as stated by Ahmes himself at the outset of the text.

However, its precise purpose remains elusive: some speculate it could serve as a teaching aid or a personal notebook, as each solution is accompanied by the directive “do the same when you encounter a similar problem.”

What is evident is its invaluable contribution to our understanding of ancient Egyptian mathematical prowess. The papyrus presents 87 problems, with 81 dedicated to operations involving fractions. It elucidates techniques for addition, subtraction, and multiplication, as well as solutions to diverse trigonometric, geometric, and applied arithmetic challenges.

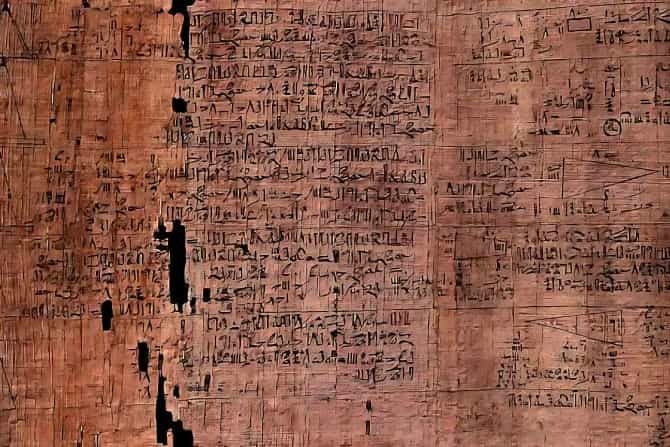

Similarly noteworthy is the Moscow Papyrus, also known as the Golenishchev Papyrus, named after its purchaser in 1883 from one of the individuals involved in the discovery of royal mummies in Deir el Bahari. This artifact, housed in the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow, shares a timeframe with the Ahmes Papyrus.

Spanning 5 meters in length and a mere 8 cm in width, the Moscow Papyrus features 25 problems, among which stands out what many consider the pinnacle of Egyptian mathematical achievement: the calculation of the volume of a truncated pyramid.

These two documents stand as the primary sources of our understanding of Egyptian mathematical knowledge, complemented by others such as the Kahun Papyrus, which hints at the Egyptians’ grasp of arithmetic progressions, and the Berlin Papyrus, which delves into solving systems of equations and the utilization of square roots. Additionally, there’s the Leather Scroll, acquired by Rhind alongside the Ahmes Papyrus, focusing on the equivalence of unit fractions (1 divided by any number) and featuring repeated fraction additions, indicative of a typical learning exercise.

At the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston resides the Reisner Papyrus, discovered in 1904, which deals with calculations pertaining to excavations and the volumes of rocks and walls.

Through the insights gleaned from these documents, we paint a picture of Egyptian mathematics as profoundly practical, geared towards everyday problem-solving. Whether determining the yield of bread from a given quantity of grain or calculating the number of bricks required for a ramp of specific dimensions, Egyptian mathematics demonstrates a keen focus on addressing real-world challenges.

Surgical Operations in Ancient Egypt

In November 2001, beneath the imposing shadow of Saqqara’s first royal pyramid, archaeologists unearthed a tomb buried five meters beneath the earth’s surface, dating back to 2000 BC.

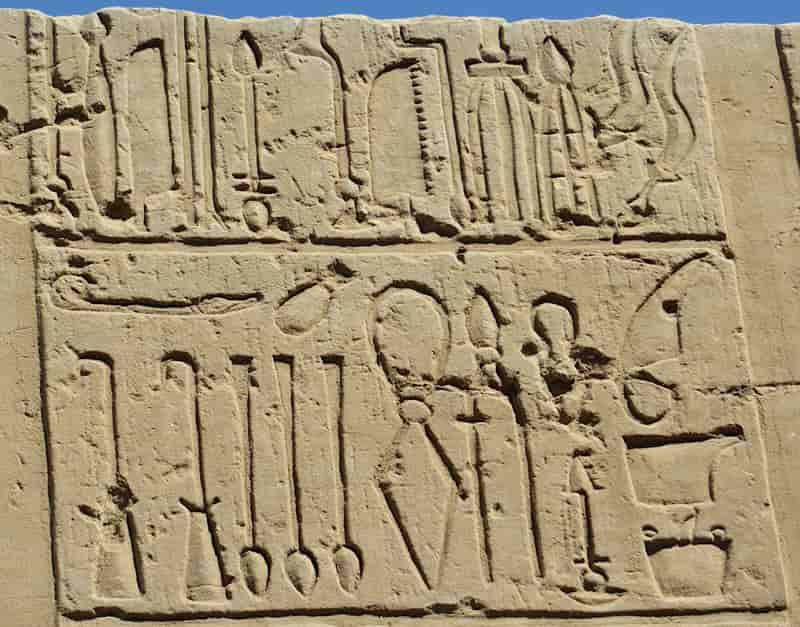

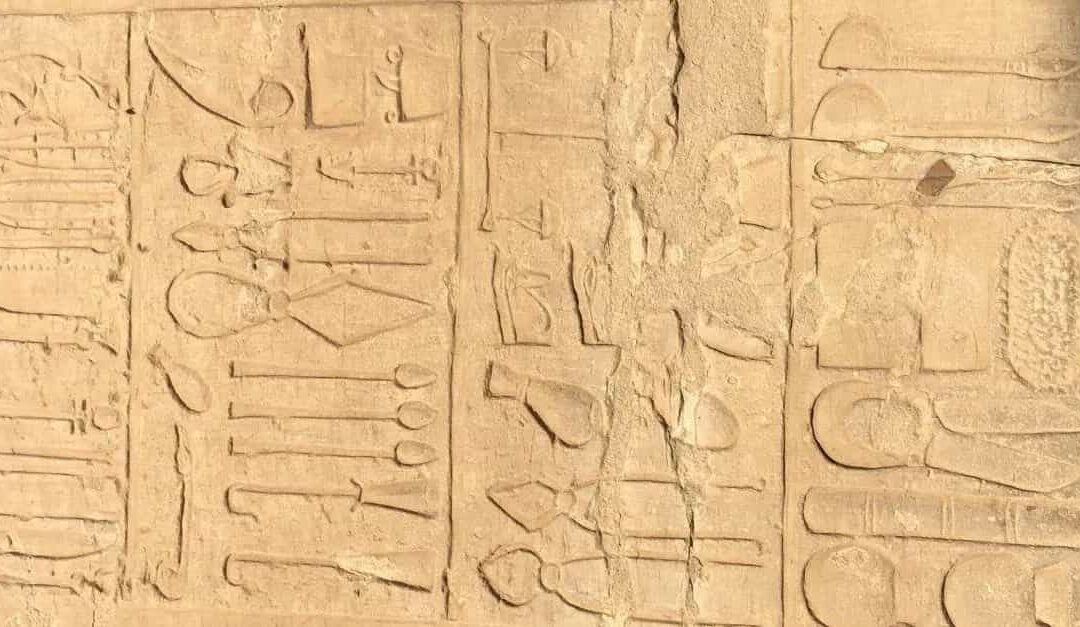

Within its confines, etched upon the walls, lay the earliest direct evidence of surgical procedures conducted in that ancient era. This tomb belonged to Skar, the chief physician of one of the pharaohs of the V dynasty.

Among the treasures discovered within were 50 bronze medical instruments, the oldest of their kind ever found. Among these tools were scalpels, needles, and even a spoon. Alongside these implements, archaeologists uncovered an alabaster altar and 22 statues depicting various gods and goddesses.

In an era where science and religion were deeply intertwined, it’s plausible that Skar held dual roles as both a physician and a priest. Yet, the nature of his medical practice remains a subject of intrigue.

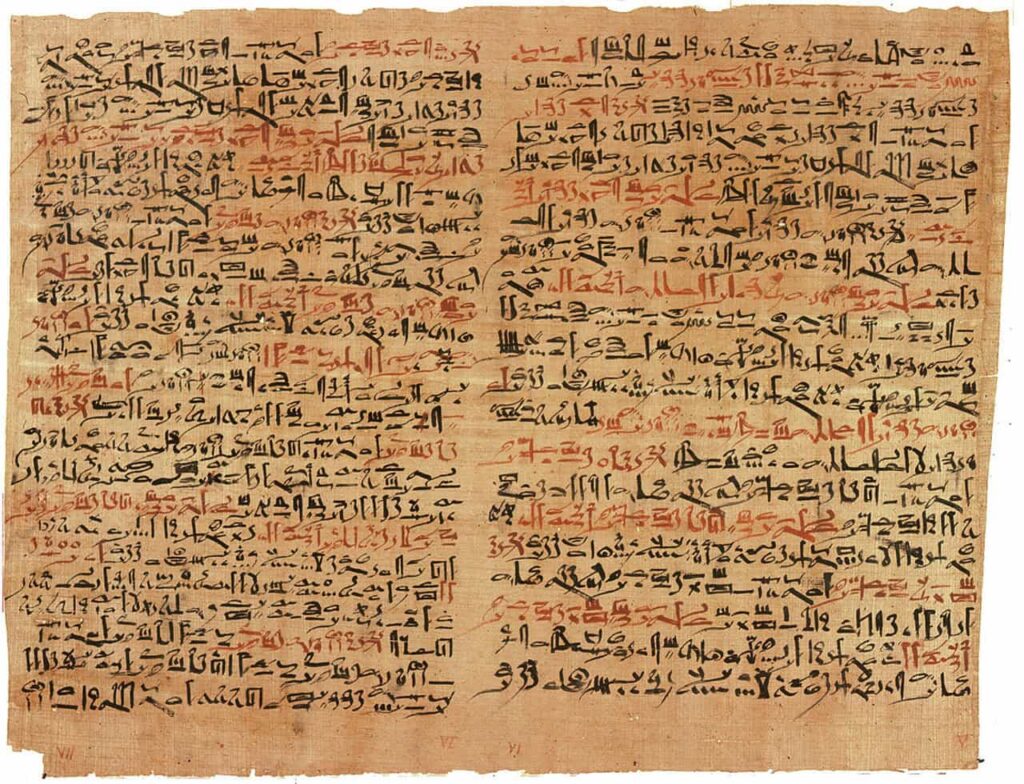

To unravel this mystery, we must journey back to 1862, to Luxor, where an American merchant named Edwin Smith stumbled upon a papyrus unlike any he had encountered before. Proficient in deciphering hieroglyphs, Smith recognized it as an ancient medical treatise.

Translated in the 1930s, the Smith Papyrus stands as an incomplete compendium of treatments for wounds and head injuries. Surprisingly, among the 48 cases studied within, only one makes mention of magic.

In meticulous detail, the papyrus delineates the steps to be taken in each case: from observation and diagnosis to examination and treatment. It provides instructions on suturing wounds using acacia thorns as needles and linen fragments as suture material.

Another notable medical manuscript is the Ebers Papyrus, an extensive scroll measuring over 20 meters in length and containing 877 recipes for a wide array of ailments. Remarkably, only 12 of these recipes suggest the use of enchantments or spells.

These texts stand as testament to the effectiveness of ancient Egyptian medical practices, earning them renown across the ancient world. Homer, in the Odyssey, attests to this, stating, “In Egypt, men have more aptitude for Medicine than any other.”

Indeed, it could be argued that various medical specialties had their origins in ancient Egypt, with practitioners specializing in fields such as dentistry and ophthalmology.

Source: Miguel Angel Sabadell, Muy Interesante