On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was shot dead along with his wife by a Serbian nationalist in Sarajevo, Bosnia, triggering the start of World War I.

Here we bring you some essential information to understand this important historical fact.

The roots of World War I lie in a dispute between opposing ethnic groups along the borders of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

The dispute quickly turned into a continental conflict due to alliances, suspicions, and rivalries. The murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, was one of the triggers for this event.

Franz Ferdinand was the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne. On June 28, he and his wife, Sophie, traveled to the Bosnian city of Sarajevo – then part of Austria-Hungary – to open a state museum.

Sarajevo was the center of riots and demonstrations in favor of Serbia. Relations between Austria-Hungary and Serbia had been deteriorating in the years before 1914. Austria-Hungary was prepared to limit the expansion and influence of Serbia, fearful of its alliance with Russia.

Serbia was eager to strengthen and secure its existence through unification with Serbian-speaking areas across the Balkans, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina.

At around eleven in the morning of June 28, the archduke and his wife were shot dead by Gavrilo Princip, a Serb recruited by a terrorist gang called ‘the Black Hand’.

The murder sparked an uprising among parts of the Austro-Hungarian empire largely populated by Serbs, but the insurrection never occurred. Instead, Princip was captured along with his fellow conspirators, including several members of the Serbian armed forces.

Both rushed to speak and the plot was revealed. The Serbian government denied any knowledge of the plan.

Some of the protests could have been organized by terrorist groups or even by the military. At the same time, anti-Serb protests broke out in Austria-Hungary, some of them orchestrated by local officials.

The Emperor of Germany was an ally and friend of Austria-Hungary, and had long supported the country’s intentions to limit Serbia’s military and political influence.

Wilhelm was particularly concerned about Serbia’s alliance with Russia, although he was personally on good terms with Russian Tsar Nicholas II, who was also his cousin.

The letters from Austria-Hungary discussed the union between Serbia and Russia and what this could mean for the future of Europe’s peace, as well as the importance of acting quickly to limit Serbia’s political ambitions.

In response to letters of appeal from their Austrian counterparts, German officials, led by the country’s chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, who promised to back Austria-Hungary.

Germany thus offered its allies what came to be known as a supporting ‘blank check’, encouraging Austria to consider a military response to the murder.

Aware that the war with Serbia would probably also involve a war with Russia, Austria-Hungary reasoned that it was vital to unleash the conflict as soon as possible to prevent Russia from ending its military reforms.

The Austrians decided to provoke a war by issuing an ultimatum to Serbia. In Germany, Wilhelm wanted to avoid giving the impression that his country was preparing for war and was trying to make sure to remain on good terms with his cousin, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia.

However, the government went ahead with its attempt to conflict with Serbia by drawing up an ultimatum with terms that the country could not accept.

The ultimatum had an expiration date of July 25. Its terms demanded that Serbia carry out a series of actions against anti-Austrian elements in the country, including the prohibition of propaganda, the elimination of certain authorities and the dissolution of Serbian nationalist organizations.

Upon delivery of the ultimatum, the Austrian army began preparations for the conflict.

It was not until July 24 that Britain’s liberal government cabinet held its first meeting on the crisis.

The gravity of the situation was clear, Serbia had mobilized in anticipation of a war with Austria-Hungary and Russia had asked for military aid. Russia was reluctant, aware that its armed forces were not prepared for a full European war.

Following cabinet discussions, Edward Gray contacted his counterparts in Europe and offered to help negotiate a solution. His help was politely rejected in Germany and Austria.

With Serbia indicating that it is unwilling to fully accept the terms of the ultimatum, the Austrian-Hungarian armed forces began formal preparations for war.

On the same day, Russia announced that it could not remain neutral if Austria attacked Serbia.

The British Foreign Minister’s attempts to resolve the crisis are once again rejected by Germany, who insisted that Russia should negotiate directly with the Austrians.

Germany was aware that French President Raymond Poincaré was visiting Russia. Knowing that these two countries also had a military alliance, Germany did not want to antagonize either of them until the official visit ended.

British Foreign Minister Edward Gray warned Germany that Britain would side with France and Russia in the event of any Austrian aggression against Serbia.

Britain had a military alliance with the French and the Russians, which had been developed in part as a response to the alliance between Germany and Austria-Hungary.

Despite an additional offer from British Foreign Minister Edward Gray to host a peace conference, at 11 am Austria-Hungary formally opened hostilities against its neighbor.

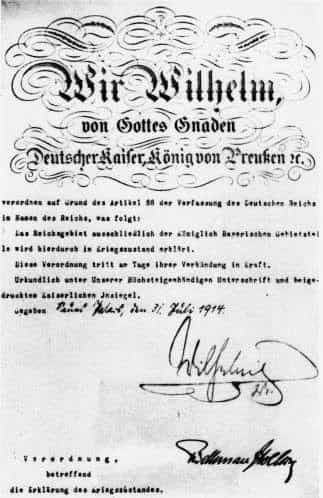

The image shows a note that appeared in the press in Vienna announcing the beginning of the war.

In response, the mobilization began in Russia. Austria pressured Germany to mobilize against Russia. Even at this stage, Germany was determined not to give the impression of wanting to turn a local dispute into a continental conflict.

This decision was made due to pressure from Serbia and because the Russian generals were aware of the amount of time necessary to obtain the necessary forces for combat.

Mobilizing along Russia’s huge borders was more complicated than the equivalent procedure in Germany or Austria-Hungary.

German officers were delighted that Russia was mobilizing first, as it allowed them to present their own mobilization as an act of defense, rather than aggression.

However, the country’s military planners had crafted their strategy on the basis of Germany by first knocking out Russia’s ally France, and then turning east to fight Russia itself.

This meant that Germany would mobilize against France and in turn meant launching an attack through Belgium, a neutral country.

Germany declared war on Russia on August 1, 1914. Following the outbreak of war with its eastern neighbor, Germany implemented the Schlieffen Plan, and the fears of the Luxembourg government were met.

Initially, the territory of Luxembourg was only a crossing point for the German Fourth Army, commanded by Albert of Würtemberg. The next day, what had been the passage of troops turned into an invasion of the entire country.

The previous day, Germany had issued an ultimatum to Belgium requesting free passage to France to which King Albert of Belgium had refused.

By sending its forces to attack France through Belgium, Germany violated Belgian neutrality, which was guaranteed in a treaty signed in 1839 to which Britain had pledged. This gave Britain a justification for going to war.

Britain issued an ultimatum to Germany to stop its advance through Belgium. When it expired at midnight, the United Kingdom formally declared war.