Upon the death of Khufu, the architect of the Great Pyramid, he was succeeded by one of his sons, Djedefre. His reign is shrouded in mysteries.

While the pyramids of Giza now stand as the most renowned symbols of ancient Egypt, our knowledge of the time they were constructed, during the Fourth Dynasty, remains quite limited.

The same applies to the rule of the third pharaoh of this dynasty, Djedefre; the data available about him are so scarce that even the correct spelling of his name is uncertain, transcribed as Djedefre or Radjedef.

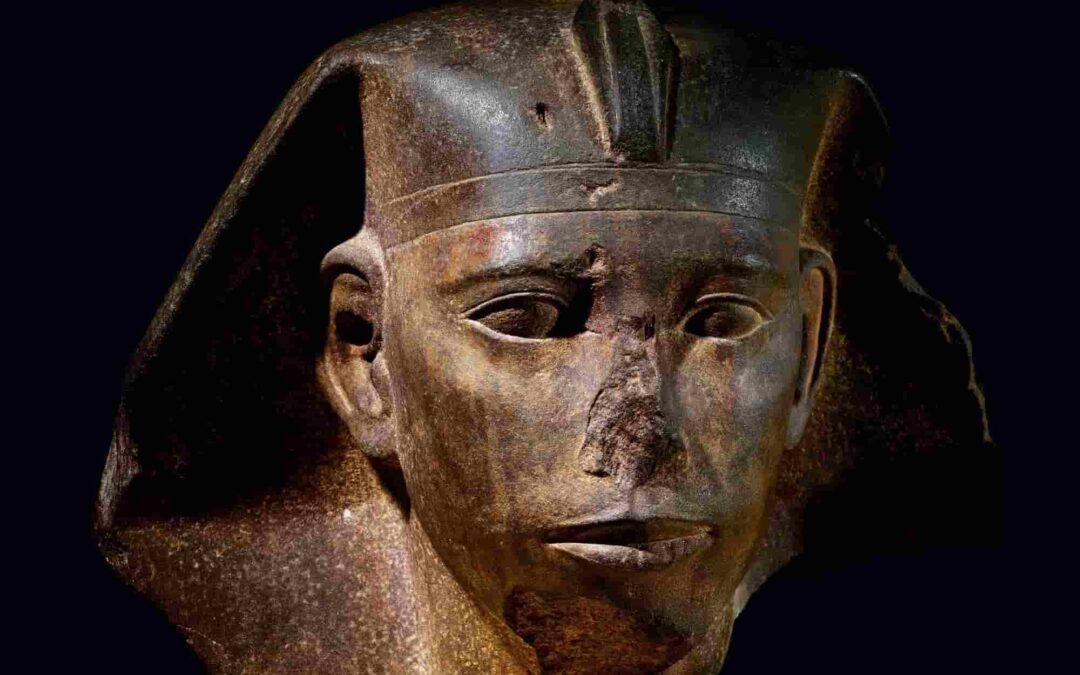

In essence, he is one of those obscure kings often overlooked in the study of Egyptian history. Nevertheless, he can be considered a representative of a pharaoh from the Old Kingdom.

A strong advocate for the centralization of the State and the worship of the solar god Ra, Djedefre left behind a monumental funerary complex, featuring a pyramid comparable in size to that of Menkaure in Giza, though now mostly in ruins.

Djedefre, born to Khufu and an unnamed Egyptian queen, would have been just another prince in the pharaonic court if Khufu’s eldest son, Kawab, had not passed away before his father.

This event likely altered the expectations for potential successors to Khufu. During this period, the Egyptian royal family functioned as a vast social organization bound by blood ties. Simultaneously, it was divided into numerous branches, and when an opportunity arose, they allied and organized themselves to secure absolute power or a more influential position in the court.

A controversial succession

Everything indicates that the succession of Khufu was stormy, although we do not know exactly how events unfolded.

A relief found in Wadi Hammamat and dating from the 12th dynasty (1991-1786 BC) places two princes, Djedefhor (Hordjedef) and Baufra, as successors of Khufu, who never ascended the throne.

In addition, the mastaba of one of them, Djedefhor (Hordjedef), was not completed and its decoration appeared damaged. This could be related to an open fight for the throne during which Djedefre would have displaced his older brother Hordjedef.

Perhaps this fact explains that a few generations later, when a rival dynastic branch linked to Hordjedef acceded to the throne, his figure was magnified and presented as a great sage. The prince also appears as the protagonist of a tale from the Westcar Papyrus.

Once he ascended the throne, and surely to consolidate his power, Djedefre married his brother Kawab’s widow, Hetepheres II, who was sister to both of them, and who perhaps married a third brother of theirs, Khafre, after Djedefre’s death.

These links are a good example of the endogamy (marriage between relatives) practiced by the ancient Egyptian royal family of this period, to which a divine nature was attributed.

As for the duration of his reign, again the problem of the scarcity of data and its difficult interpretation arises.

The Royal Canon of Turin (Turin Papyrus) – a document dated to the time of Ramses II that mentions the names of the kings of Egypt from the beginning of its history – leaves the place where Djedefre’s name should appear blank, but notes next to it that his reign lasted eight years.

Based on this data, some scholars suggest that Djedefre reigned for nine years. However, researchers such as Miroslav Verner question the accuracy of the sources of the compiler of the Canon of Turin for Dynasties 4th and 5th.

On the other hand, in the pyramid of Khufu, in one of the moats destined to the funeral boats of the pharaoh, a graphite with the name of Djedefre was discovered, which mentions the tenth or eleventh census of the reign.

This would indicate a reign with at least a couple of years more than those indicated in the aforementioned Canon, although it must also be taken into account that the censuses in that period were irregular and did not have to be annual or biannual.

Faced with this uncertain situation, we can only assume that Djedefre reigned for around ten years, perhaps one more.

The pharaoh, son of the Sun

Djedefre was the first pharaoh to declare himself Son of Ra, a name that since then would be added to the royal title, already formed by the names of Horus, Nebty (the Two Ladies, that is, the vulture and the cobra that symbolize Upper and Lower Egypt), Golden Horus and Nesu-Bity (Lord of the Two Lands).

This new title must be considered as one more element in the so-called “solarization process” of the Egyptian monarchy, that is, the progressive transformation of the solar god Ra into a state deity of Egypt.

This process had begun timidly since at least the Second Dynasty and acquired increasing relevance, as indicated by the proliferation of monumental constructions associated with the solar cult, in particular the pyramids, obelisks and sphinxes.

Another characteristic feature of Djedefre’s reign was the impulse given to the centralization of the State. The succession crisis that brought him to power does not seem to have disturbed the functioning of the pharaonic administration.

As in the time of his grandfather Sneferu or his father Khufu, under Djedefre the government showed a high capacity to accumulate resources. The best example of this is found in the construction of his great funerary complex in Abu Roash.

The pharaoh had to pay the many workers and craftsmen employed in the construction of the complex, as well as supply the necessary materials, some especially expensive because of the distances from which they had to be transported.

Such was the case of the pink granite, from the quarries of Aswan, in the first cataract of the Nile, and of the red quartzite extracted in the quarries of Gebel el-Ahmar, located near Heliopolis.

A large funeral complex

The pyramid complex of Djedefre – called in ancient times “Djedefre is a Shining Star” – was erected at Abu Roash, about ten kilometers north of Giza.

Investigated and partially discovered by different archaeologists, it was not until 1994 that a French-Swiss mission led by Michel Vallogia undertook a systematic study of the site, beyond the pyramid and its burial area.

Traditionally it has been considered that the fact that Djedefre located his funeral complex outside the Giza compound was due to the difficulties that arose after the death of Khufu and that it was a way of distancing himself from his predecessor.

However, if we analyze the situation of the funeral complexes of the first three kings of Fourth Dynasty we can see that Sneferu, Khufu and Djedefre located their burial place – in Dahshur, Giza and Abu Roash, respectively – at some distance from that of their predecessors.

The pyramid of Abu Roash

Djedefre’s funeral complex was designed in a similar way to that of his father Khufu, although it does present some novel elements.

It consists of a central pyramid with its attached funerary temple and an adobe wall that surrounds the complex.

Traditionally it has been believed that the pyramid was never finished, but from the recent investigations of Michel Vallogia it has been possible to show that the monument was finished in its entirety and that the lack of construction material is due to the fact that the site has been looted from Roman times.

From the archaeological evidence it has also been possible to reconstruct the original measurements of the pyramid. It is known, thus, that each side measured 106.2 meters, and it is estimated that its height ranged between 57 and 67 meters.

A singularity of the Djedefre pyramid is that it was erected on a natural mound from which you could see the delta of the Nile, to the north, and Dahshur, to the south, where Djedefre’s grandfather, Sneferu, had erected two pyramids.

Djedefre’s brother and successor, Khafre, also built his pyramid on a mound on the Giza plateau, so that even today his funerary monument seems higher than that of his father Khufu, when the opposite is true.

On Djedefre’s death there was surely a new fight for the throne, in which perhaps one of his sons intervened, such as Baka or Setka.

This is suggested by the appearance of a royal name ending in -ka in the unfinished pyramid of Zawiyet el-Arian. But, if there was conflict, the one who was ultimately victorious was Djedefre’s brother, Khafre, builder of the second largest pyramid in Egypt and, perhaps, the Sphinx of Giza.

- Sources:

- National Geographic

- Egypt in the Old Kingdom. Juan Carlos Moreno García. Bellaterra, Barcelona, 2004.

- History of the pyramids of Egypt. José Miguel Parra. Complutense University, Madrid, 2008.