A powerful infantry, an efficient corps of war chariots and a large fleet sustained the conquest of Thutmose III, who fought a fight to the death against the kingdom of Mitanni, Egypt’s greatest Asian enemy.

He was not destined to reign. Thutmose III only came to the throne of Egypt because his father, Pharaoh Thutmose II, and his Great Royal Wife, Queen Hatshepsut, had no male descendants.

So it was he, son of the pharaoh and a secondary wife, who ended up ruling the Nile country. In this case, chance was generous with Egypt because Thutmose had all the necessary qualities for a good ruler and one more: his extraordinary military capability, which, coupled with foolproof courage, earned him the loyalty of the most powerful army in the Middle East.

At the command of these troops, Thutmose III forged an empire that ran from present-day Syria to the fourth cataract of the Nile, in what is now Sudan. With this, the dominions of Pharaonic Egypt reached the maximum extension of all its history.

In pursuit of this ambitious expansion, the army fought up to seventeen times in Asian lands, between the Sinai Peninsula and the Euphrates River.

Along this river stretched the dominions of Mitanni, which at that time was Egypt’s deadliest enemy. The two states clashed violently over the dominance of Syria, where all the Middle Eastern trade routes converged.

The predecessors of Thutmose III had developed professional armed forces, but it was he who made them an effective instrument of conquest and defense. The pharaoh was the commander-in-chief of all the armies of Egypt, although he could cede functions to his crown prince.

Various inscriptions highlight that his son, the future Amenhotep II, learned to use weapons from his childhood and, already as a sovereign, demonstrated his skill in handling chariots and bows, both on training grounds and on the battlefield. But what was the armed wing of Egypt like and how did it work?

Infantrymen, ships and chariots

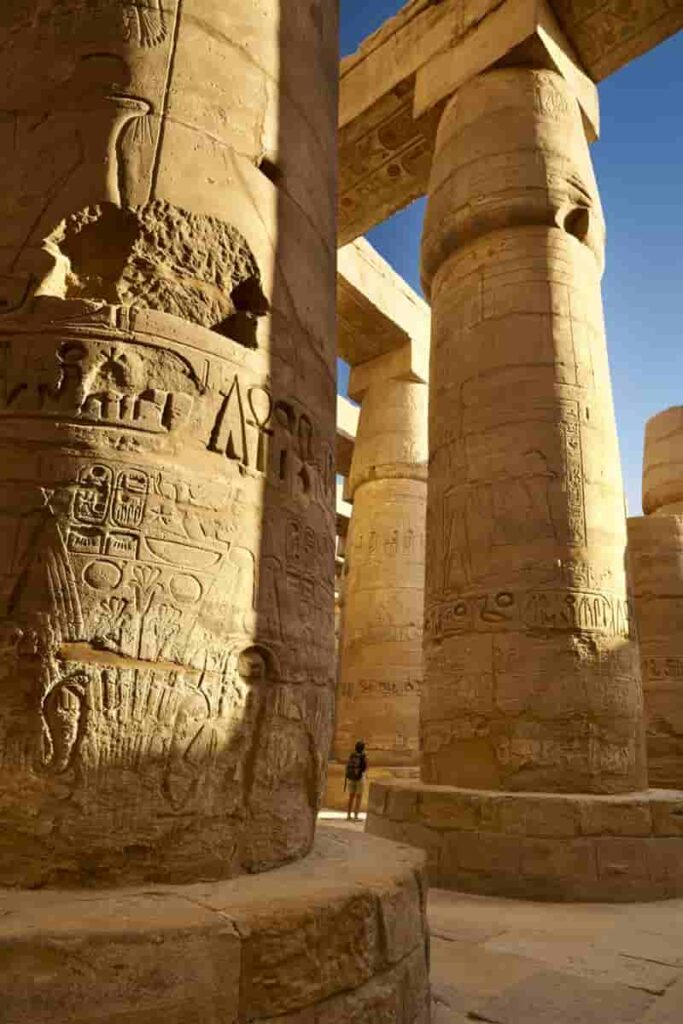

Below the king, it was the vizier, as the administrative head of the country, who gave the instructions to the officers of the two military regions with capital in Memphis and Thebes, cities that had large barracks. The main sections of the army were the infantry, the river fleet, and the chariots.

As for the war chariots, the basic unit was a squad made up of 50 vehicles, which were divided into detachments of five or ten carriages.

The basic infantry and fleet unit was a company of between 200 and 250 soldiers, under the command of a standard bearer. These units could be divided into detachments of 50 men.

Several companies of infantry formed a battalion, at the head of which was a commander, and several battalions constituted a large unit, led by a general.

The soldiers, who mostly came from the center and south of the country or from Nubia, had their bodies hardened by fighting practices and were used to making long marches to reach their objective.

During the Megiddo campaign – in which the king took this fortress, where Mitanni’s allies had gathered – the army covered the 220 kilometers that separated the border square of Tjaru and Gaza City in ten days.

Each company in the fleet was attached to a ship. These ships, which were used to transport soldiers and supplies, received names such as La vaca bellicosa, El novillo or Amado de Amun.

Military expeditions against Nubian territory were carried out with ships of the river fleet that crossed the Nile. But ships could also be sent to the coasts of the Near East.

During the sixth Asian campaign, which concluded with the successful capture of the city of Qadesh, an ally of Mitanni, an Egyptian squadron sailed to the ports of the Canaanite coast, in an amphibious action that allowed the conquest of various enemy territories.

And in the eighth campaign, in which Egyptians and Mitannians clashed directly, an army column traveled the more than 400 kilometers that separate the port of Byblos and the Euphrates bank transporting dismounted barges on ox-drawn carts.

Once the objective was reached, they assembled the boats and crossed the river to the amazement of the Mitannians. In fact, the importance that Thutmose III gave to navigation materialized with the construction of port facilities in the eastern delta, known as Peru Nefer, “Good Voyage”, which facilitated commercial and military communications with Canaanite coastal towns.

The difficult military campaigns

Military operations were designed with the weather in mind. Except in emergencies, campaigns against African enemies were carried out in winter and expeditions against Asian territories were prepared for summer.

In this way the ancient Egyptians avoided the harshest heat and cold, which could become fatal enemies.

In campaign, the movements were ordered by means of drums and trumpets. The weight of the battle was carried by the infantry, in which two types were distinguished: the heavy, whose components were armed with shield, spear and ax, and the light, provided with javelins or bows and arrows.

There were also slingers. As for the war chariots, they were used mainly to escort the infantry in the open field, harass the enemy when they formed for battle and, if they were defeated, pursue them in their retreat..

Each chariot had one or two side quivers where javelins, bows and arrows were kept. The cars were manned by two men: the driver, an expert in handling reins and weapons, and the combatant, who was in charge of protecting his partner.

For his part, the driver had to take responsibility for feeding the horses and keeping the vehicle in good condition.

When it came to taking a walled city, the Egyptians could storm it with ladders and battering rams while archers fired at the defenders, or they could besiege it.

In the latter case, they cut down trees and built forts that would prevent contact between the besieged and the outside.

This system is described in the chronicles of the Battle of Megiddo, which surrendered after a seven-month encirclement by the troops of Thutmose III.

Repeated rebellion could have tragic consequences for the defeated. Thutmose III’s son and successor, Amenhotep II, personally executed seven Asian leaders and returned to Egypt with their corpses hanging on the ships of the fleet to display on the walls of Thebes and Napata.

Excellent soldiers participated in these campaigns. Among the most successful of the time is General Djehuty, the first governor of the Asian lands, to whom later literature attributed the conquest of the city of Joppa “The Taking of Joppa” by means of men hidden in baskets that were introduced into the fortress.

It is also worth remembering Commander Amenemhab, who accompanied the king on different expeditions and who was promoted and rewarded several times due to his heroic behavior, which was not limited to the battlefield: on one occasion he cut the trunk of an enraged pachyderm that charged against Thutmose III while the king hunted elephants.

Soldier of ancient Egypt

The troops consisted of professional Egyptian soldiers, whose relatives resided in military colonies. When they left active service, they could continue to enjoy the fiscal advantages of those colonies, as long as one of their sons replaced them in the fulfillment of their military duty.

To avoid fraud, periodic inspections were carried out. The military barracks regularly received bread, beef, vegetables and beer. When they marched against the enemy, they were given the rations calculated by the scribes and provisions delivered by the leaders of the territories they passed through.

The scribes, in addition to the quartermaster, were in charge of recruiting. Military life was not without its attractions: in addition to the maintenance and usufruct of state lands, soldiers could seize the spoils of the vanquished and slaves, and were rewarded with honorary titles, promotions in rank and a generic decoration: the “honor gold”, materialized in gifts from the pharaoh that included weapons and gold and silver jewelry.

Source: National Geographic