In the passage from the 4th to the 3rd millennium BC, the first pharaohs extended their authority throughout the entire Nile. In the 19th century their tombs were found at Abydos.

For their eternal rest, the first kings of Egypt chose a rugged and desert area on the western bank of the Nile at Abydos; an area that we now know as Umm El Qaʻāb.

But why did they decide to be buried in this secluded place? We find the answer in the very ideology of Egyptian royalty and society.

In Abydos not only are the kings of dynasties I and II buried, but also their predecessors, the kings of the Protodynastic period, who had completed the unification of the country, so that the new pharaohs appeared as their successors.

In this way, the location of the royal tombs justified royal power and conferred legitimacy on it. But there is more.

The architecture of the new pharaonic tombs was changing, in an evolution that symbolizes the transition to a new political order, in which the pharaoh assumed a central place.

Beliefs about death came to reflect a hierarchical society, presided over by the king by virtue of his dual role: as a mediator between gods and mortals, and as a guarantor of cosmic order in the face of chaos.

A court underground

Under the first pharaohs of the First Dynasty (around 3065-2890 BC), the royal tombs, dug out of the desert floor, consisted of a main chamber lined with wood, which housed the body of the king, and by various secondary chambers.

These were also used as burials, and the quality of the remains found in them shows the high social position of the people buried there.

The structure of these funerary complexes indicates that the royal tomb and the others were built and occupied at the same time; all were covered when they received the bodies of the deceased.

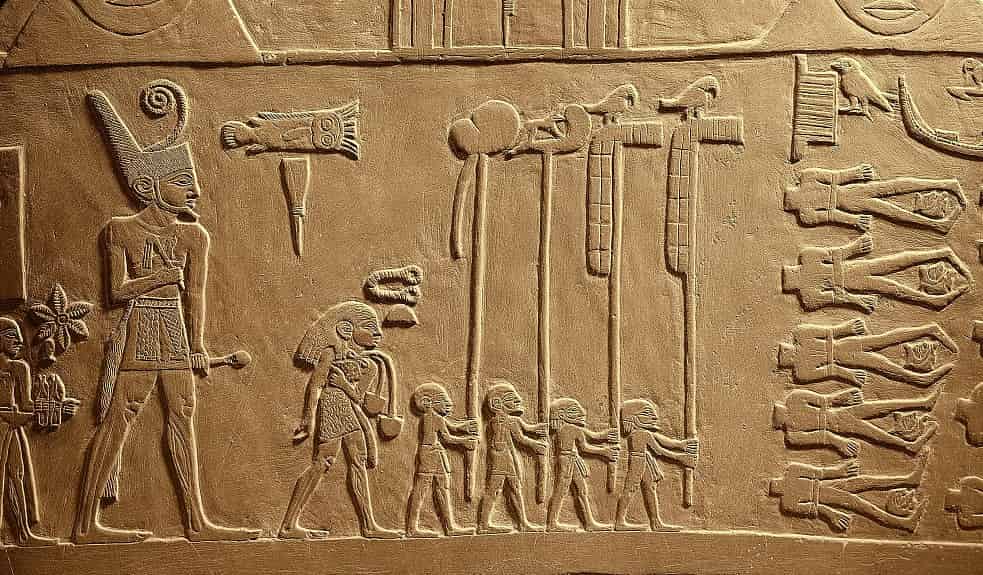

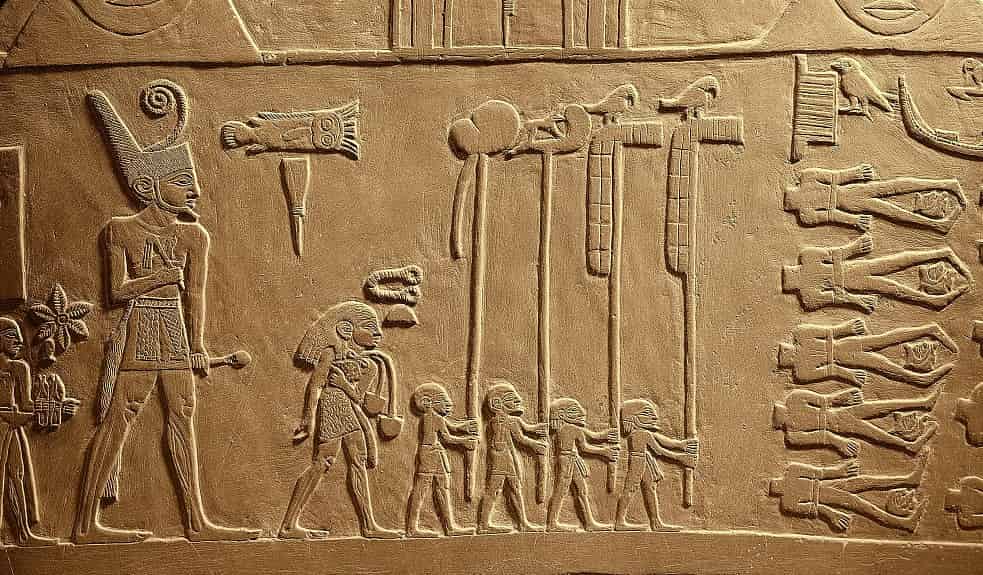

In addition to their tombs, the first three rulers of unified Egypt (Aha, Djer, and Djet) and the mother of the fourth, named Merneith, built colossal adobe burial enclosures a kilometer from their tombs.

Djer’s was 100 meters long by 55 wide, and the surrounding wall, up to three meters thick, could reach eight meters high.

Outside, the walls of these enclosures were decorated with recesses and projections; Inside, an immense open space housed chapels of worship to the deceased king.

During the second half of the First Dynasty, from the reign of Den, son of Merneith, the king’s burial chamber – the largest in Umm El Qa’ab – was lined with stone and a new element appeared: the access stairway to the chamber, which allowed to cover the royal burial before the death of the king.

At one end of Den’s tomb was another underground room with a separate staircase; In this enigmatic chamber a precedent of the serdab has been seen, the space that in the funerary precincts of the Old Kingdom housed the statue of the ka or vital breath of the deceased person.

The first five pharaohs of the Second Dynasty were possibly buried at Saqqara, 400 kilometers down the Nile, but their last two kings, Peribsen and Khasekhemwy, rebuilt their tombs and erected burial grounds at Abydos.

However, the tombs of these sovereigns differ significantly from those of the kings of the First Dynasty.

They remain underground adobe structures, but the main chambers are smaller in size and have secondary storage chambers. And there are no other burials associated with royal tombs.

Peribsen’s funerary enclosure is similar in size to its predecessors, although the thickness of the walls is much less.

The grave of his successor, Khasekhemwy, shows clear parallels with that of the pharaoh who followed him, Djoser, the first king of the Third Dynasty, with whom the Old Kingdom began.

Djoser returned the royal necropolis to Saqqara and added the previous funerary traditions: he brought together in a single complex the tomb, the funerary enclosure, the chapels and the warehouses, elements that until then had been separated.

Although looted, the royal tombs at Abydos have provided a wealth of information about the early steps of ancient Egyptian civilization.

Its subterranean rooms contained everything necessary for a pleasant existence in the Hereafter, from luxurious objects of prestige, such as finely crafted stone jugs, to food, oils, ointments and clothing.

The country of the first dynasties

Despite the apparent cultural and political unification of the Nile Valley (Upper Egypt) and the Delta area (Lower Egypt), in the passage from the 4th to the 3rd millennium BC, most of the nomes (territorial division) were walled.

They also show a lack of uniformity in their planning and design, which suggests an important local initiative and a weak central authority.

The imposition of royal authority and the assertion of royal power would be manifested in the great constructions of Khasekhemwy, like the formidable temple he built in the city of Hierakonpolis or his vast funerary enclosure in the necropolis of Abydos.

The first splendor of Egypt

The birth of the unified kingdom (under the First and Second Dynasties) was inseparable from the emergence of political centralization, social stratification, a powerful economy, and very powerful religious institutions.

Pharaoh’s titles (such as “Horus,” a falcon god related to the sun) indicated the divine character of his office. This god-king directed all the activities of the country with the help of a vast bureaucracy, headed by the vizier.

Such a position is documented from the Third Dynasty, but it probably already existed in the time of Narmer, the last ruler of Dynasty 0 (Naqada III) and founder of the First Dynasty.

The increasingly numerous royal officials had to be fed, and for this the State was busy collecting taxes in kind that were stored, such as cereals.

At the end of the Second Dynasty, “the house of redistribution” divided the proceeds between the employees of the administration and the temples.

In this incipient administration, the king had in his hands all the wealth of the country, since he controlled local trade with taxes and directly dominated international trade, which had reached great breadth.

Below the king, officials, and temple personnel were qualified artisans, and the lowest stratum of society was occupied by ranchers and farmers.

It was the work of these humble peasants that made ancient Egypt a world power as early as the First Dynasty. The tillage of the lands where the Nile deposited its fertile silt during the annual flooding of the river produced the agricultural surpluses necessary for the sustenance of the bureaucrats and soldiers, and to fuel commerce.

In Abydos, five thousand years after its construction, the tombs and thick adobe walls erected by the kings of that powerful and respected country continue to defy the dust of the desert.

Source:

National Geographic

History of the Egyptian civilization. DJ Brewer. 2007.

Ancient Egypt . BJ Kemp. 2003.