Deir el-Medina (Convent of the City) is an Egyptian town founded by Thutmose I, pharaoh of the 18th dynasty.

At the entrance of the Valley of the Queens and near the Valley of the Kings, are the remains of what was the most prosperous settlement of workers and artisans of Ancient Egypt:

Set Maat “The place of Truth” (Egyptian name), Deir el -Medina (Arabic name), a town located in a small valley in the Theban region, near the hill of Qurnet Mura , on the west bank of the Nile, in front of Thebes, present-day Luxor ( Egypt).

For a long time it suffered looting, since it was a place well known for the abundance, beauty and richness of the objects that were in its vicinity.

However, many archaeological evidences are still preserved: tombs, houses, grave goods, which make this place the best known ancient Egyptian town.

History

At the beginning of the New Kingdom, Thutmose I, decides to abandon the construction of mastabas and pyramids and orders to begin his tomb in a more protected place, excavating the mountainside, founding Set Maat (Deir el -Medina) as a place of residence for workers and craftsmen engaged in construction.

His successors built their tombs in the same place for about 500 years, during which time the town was inhabited.

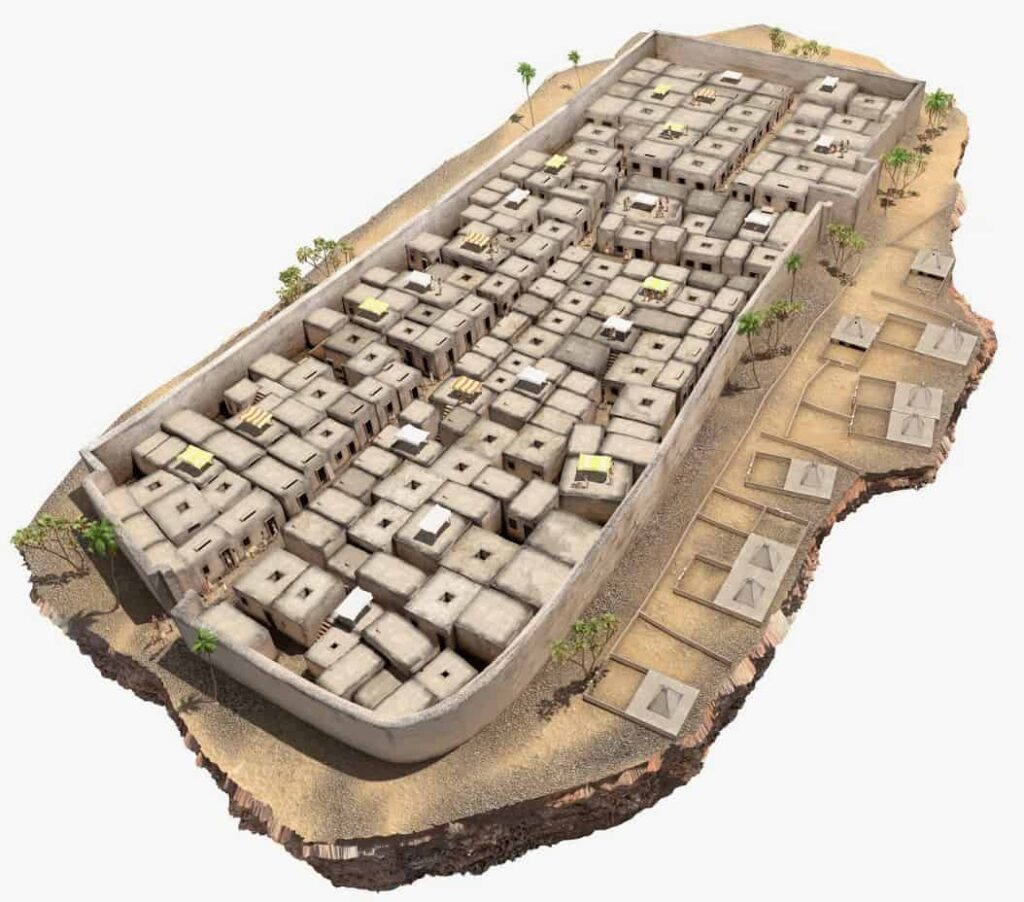

It was founded with reduced dimensions: forty houses surrounded by a wall, but it never stopped growing, reaching its maximum splendor in the times of Seti I and Ramses II, with fifty houses inside the walled enclosure and seventy outside it.

It was abandoned in times of Smendes, around 1170 BC. A second revival occurred with the Ptolemaic Dynasty, but it did not reach the previous prosperity and was soon abandoned again.

The town

The town was simply called Pa Demi, the village. The wall delimited a rectangular area within which the dwellings were distributed along a street that began at the gate of the enclosure and crossed the entire town. The rear wall of each building was attached to the wall.

They were single-story houses, with stone pavement and adobe walls, materials that were shared with the rest of the buildings, excluding the temples and tombs. They were roofed with trunks covered with palm leaves and mud.

Rectangular in plan, they had four small rooms, one after the other: the first was a hall with an altar, and the last seems to be the kitchen, since ash remains have been found in it. From there a ladder started to go up to the terrace.

The furniture and other everyday objects, such as mirrors, board games, are known thanks to the tomb of the architect Kha and his wife Merit, who has arrived intact with a rich trousseau, although that of the workers was probably more modest.

Citizens

We know the details of their daily life thanks to the ostracas, pieces of pottery, or limestone, used as a support for their annotations, since the papyrus is very expensive, which have been found in the city garbage dump.

The workers were part of the social base, along with the peasants, but there were notable differences between them depending on whether they were artisans, common workers or carried out some administrative work: scribes, doctors, etc., in addition to all the people necessary for the operation of the city: all those tasks necessary for self-sufficiency, including agricultural ones.

The State wanted few contacts with the outside, to maintain as much discretion as possible about the construction of the tombs, so it supplied everything necessary, including the transport of water from the river, since the town was located in a desert area.

Work

Before starting any work, artisans and workers signed a contract in which the duration of the work and the salary were adjusted.

This was paid in kind, in the form of larger or smaller rations depending on the category of each. In addition, families cultivated small plots and raised pigs, goats and sheep.

The work period was ten days, at the rate of eight hours a day, and began at sunrise. When finished, they did not return to the town but spent the night in temporary houses, built next to the Valley of the Kings.

Scribes

They closely followed the works and recorded any events, the daily progress of the work, the material used, absences from work, etc.

This work was called “The Diary of the Tomb”, and it was carried out by the “Scribe of the Tomb” who was the representative of the state in the town. All the bureaucratic aspects were handled by him.

Doctors

They had the main obligation to keep the workers in shape, although they also served the rest of the population. It was a task performed by the “Wise Man” who was believed to have supernatural powers and extensive knowledge (for the time) of medicine.

Workers

They were in charge of excavating the graves on the mountainside. They worked in crews divided into two groups, each of whom was headed by a foreman and an assistant.

Since some galleries reached 100 meters, artificial lighting was used based on oil lamps supplied by the royal warehouse in the area.

The masons shaped the different rooms, carefully hiding the access, to avoid as much as possible the looting of the tomb, which was already a common practice.

Craftsmen

They went into action when the rooms were ready, being responsible for the decorations. They had to paint the walls, most of the time with the instructions of the Book of the Dead, make the statuettes that represented the king and his servants, ushabti, and make all the trousseau for him, to be used in the afterlife, of course, richly decorated.

Leisure

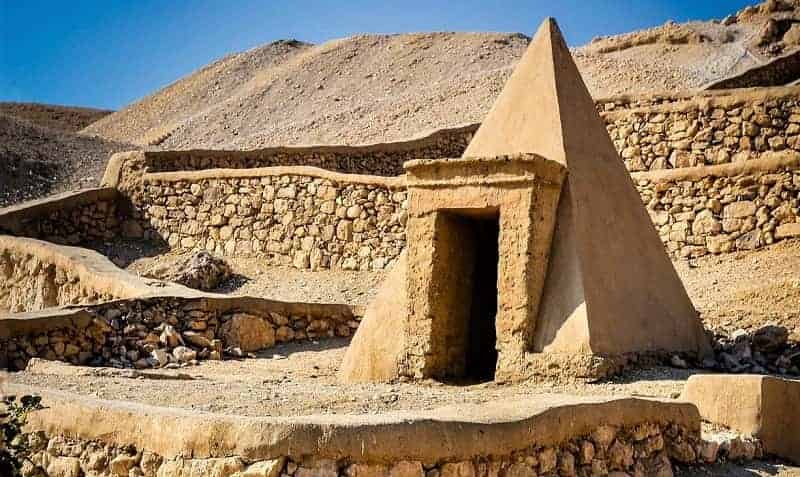

Every ten days they returned to their homes, dedicating the day off to build their own tombs, in which they have left us beautiful paintings, visit nearby places of worship or do work for others to round off income.

Almost all the workers were organized in brotherhoods, and took advantage of the days off to meet.

The first documented strike

In times of Ramses III, towards 1166 BC, the payment of wages was delayed more than usual, and the workers, driven by hunger, abandoned their jobs and took to the streets to achieve their objectives.

The events are related in the Papyrus of the Strike of the reign of Ramses III, preserved in Turin , Italy. The strikes continued until the end of the 20th dynasty.

Summary

Deir el-Medina had its best time with Ramses II, with the decline that began with the 20th Dynasty, disorganization also reached there, until the total abandonment with the 21st Dynasty, which moved the capital to Tanis in the Delta and abandoned the necropolis Theban: Deir el-Medina no longer had a reason to exist.

Archaeological remains in the area

The town of artisans

The Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Queens

A Ptolemaic temple

The necropolis: with the tombs of Sennedjem, Kha (the only one intact) and Pashedu.