The pharaohs enriched Egypt’s principal cult site, dedicated to Amun, the great god of the new kingdom, for more than two millennia. Intef II, king of the 11th dynasty, began construction on the temple of Amun-Re in Thebes, where the modern town of Karnak now resides, more than 4,000 years ago.

It was the core around which dozens of pharaohs built and remodeled one of the wealthiest and most impressive worship sites in antiquity, with over two hundred constructions documented by archaeologists.

The sanctuary of Amun in Karnak began to be built following a long series of rites to purify the site that was to be consecrated, as with any Egyptian temple. It’s important to remember that an Egyptian temple was not where people went to pray, but rather where the god lived (it was his “mansion”). Priests are known in Egypt as hemu-netjer, which means “servants of the god.”

The “stretching of the rope,” pedj-sesh, was the first ceremony conducted when a temple was inaugurated, and it dates back to Dynasty I. (3065-2890 BC). The priests used this ceremony to orient the temple’s primary axes towards noteworthy targets, such as geographical features or astronomical locations.

In the case of Karnak, the east-west axis was oriented toward the point where the sun rises on the winter solstice (between December 20 and 23), so that if we stand on the pier before the temple’s entrance on that day, we will see the sunrise over the eastern gate, Bab el-Makhara, which is nearly 600 meters away.

Then, to purify the land, foundation trenches were dug, the first adobes were built, and foundation deposits were laid, which were materials buried in the foundations of buildings to commemorate their construction and attract the gods’ favor.

The edifice was cleaned with fumigations and readings of sacred scriptures after it was completed, and it was ready to be consecrated to the god who would dwell on it.

THE HIDDEN ONE’S HIDDEN RESIDENCE

Amun, often known as “the hidden one,” was the god who was to live in Karnak’s temple. Amun was originally a local god of Thebes, but he rose through the Egyptian pantheon to become the major god, linked with the sun god Ra.

His image was preserved in a large boat called Userhat in the temple’s most sacred chamber in the inner sanctum.

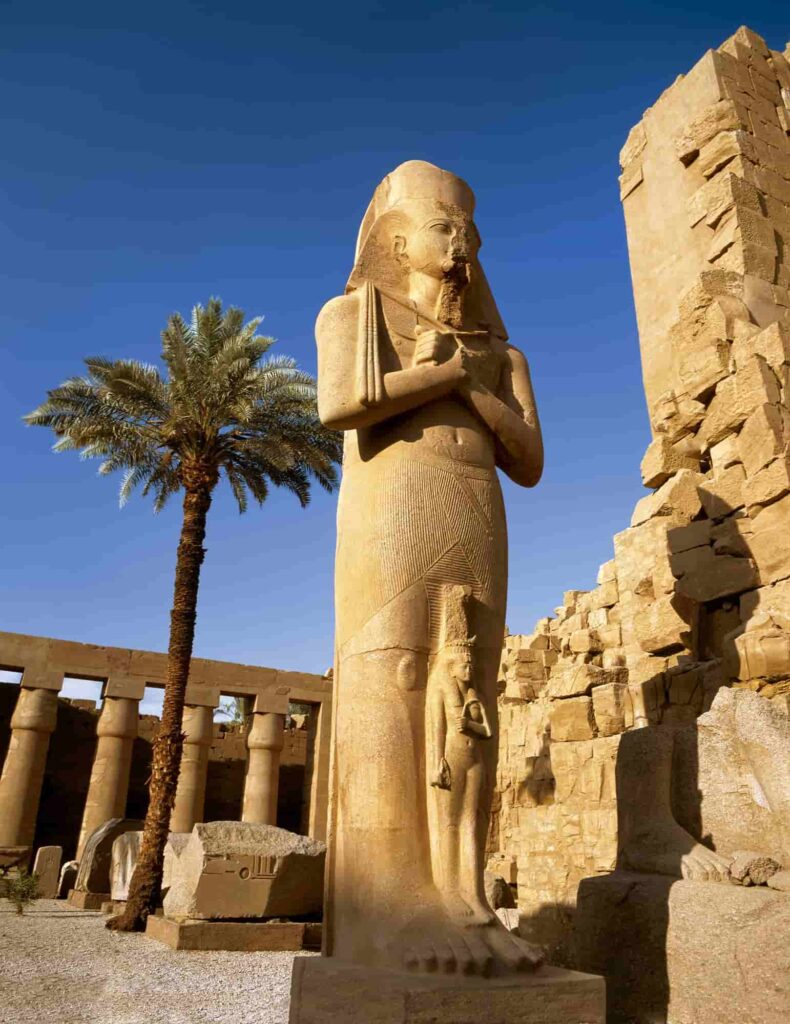

This pier is connected to the temple by a sphinx-lined road. The Karnak sphinxes are cryosphinxes, meaning they have a ram’s head, as this is one of the animals associated with the god Amun, and they served as guardians of the procession routes.

Because ordinary Egyptians could not enter the sacred precincts, they had to rely on symbolic intermediaries to communicate their wishes to the gods. This function was carried out in Karnak by the sculptures of the sage Amenhotep, son of Hapu, royal scribe, and architect of Amenhotep III, which are located outside the temple’s entrance and read:

«O people of Karnak! Come over to me, Amun! Your requests will be communicated to me! » With their passionate caresses, the numerous Thebans who asked his help cleaned the statues.

PYLONS, LAKES, AND OBELISKS

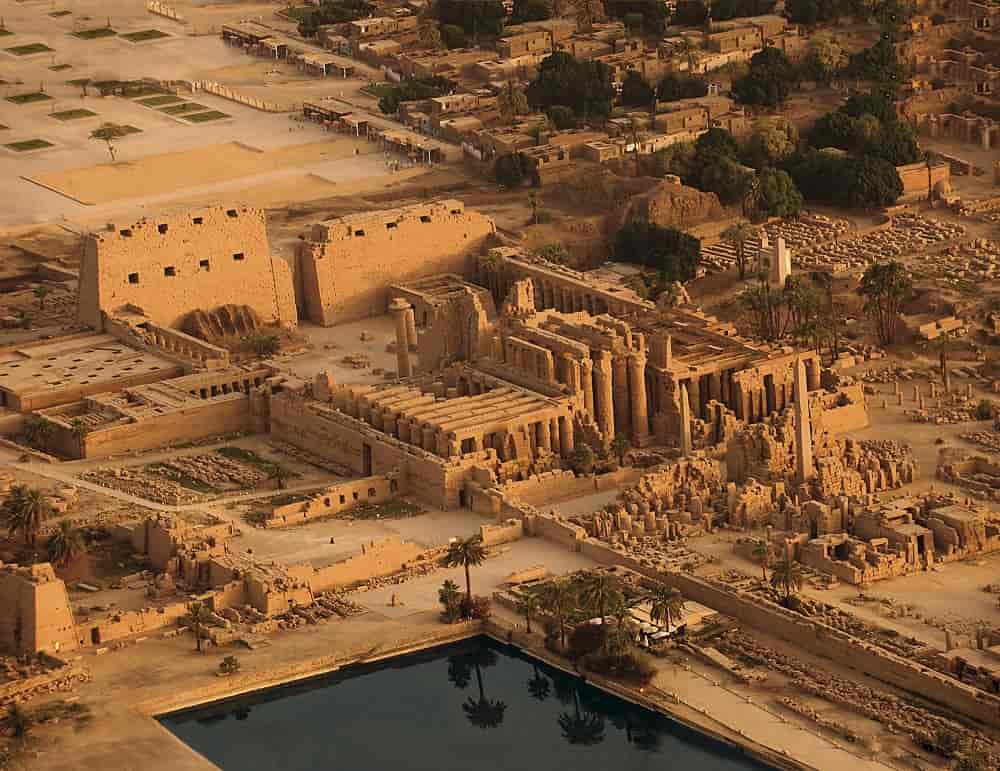

The Egyptian temple symbolizes the newly created universe. It symbolizes the benben, or primordial hill, which erupted from the Nun, the chaotic primordial ocean, with creation. As a result, the massive twelve-meter-high wall surrounding the sacred sanctuary at Karnak, spanning 550 by 523 meters, is built-in waves rather than horizontal adobe courses.

The sacred lake of Karnak, measuring 130 by 80 meters and rebuilt by Taharqa order Pharaoh, is the most important aquatic region within a temple’s enclosure (690-664 BC).

A pylon (bekhenet), a massive entryway with two enormous towers on either side, was used to enter the enclosure. ‘A gigantic gate in front of Amun-Re, totally covered in gold and sculpted with the god’s image in the form of a ram, embellished with actual lapis lazuli and intricately carved with gold and valuable stones.

Its exterior face is covered with lapis lazuli stars on both sides, and it is paved with flawless silver. Colossal sculptures were constructed in front of the pylons; one of Amenhotep III stands 21 meters tall in front of the tenth pylon.

Up to 10 pylons can be seen in Karnak, six in the main axis and four in the direction of the temple of Mut, Amun’s consort. The largest is the one on the main façade, created by Nectanebo I. (380-362 BC). It has a side length of 113 meters.

The pylons were occasionally filled with debris from demolished structures. The White Chapel of Sesostris I, the Calcite Chapel of Amenhotep I, the Peristyle of Tuthmosis IV, and the Red Chapel of Hatshepsut have all been restored thanks to stones discovered in the third pylon of Karnak, erected by Amenhotep III.

Tall cedar wood masts were erected on the pylons’ facades, with the ends coated in electro (a gold and silver alloy) and colored banners. Large bronze anchors were used to securing the masts. There are still big windows in the first pylon of Karnak that identify the location of these anchors.

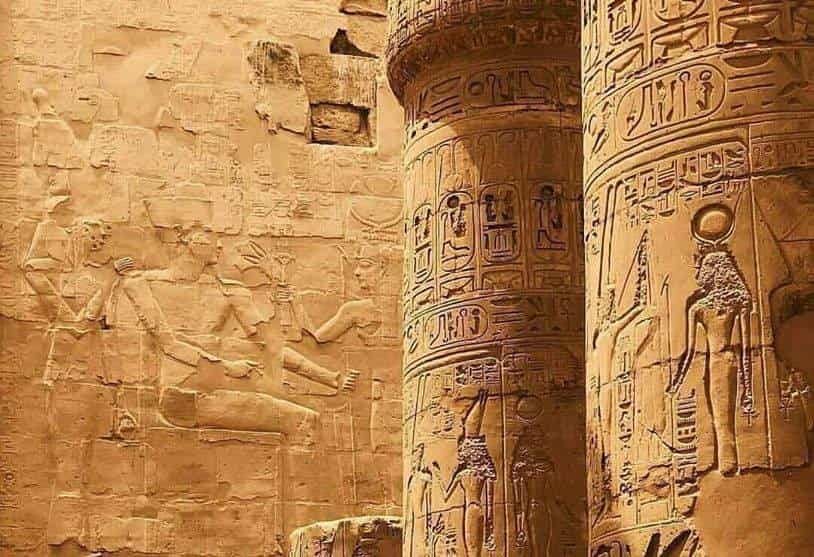

The obelisks, truly petrified rays grouped in pairs, were another aspect of solar iconography that adorned the front of the pylons.

It wasn’t easy to get to Karnak, which was 220 kilometers away. In operation involving almost a thousand sailors, a representation uncovered in Deir el-Bahari depicts a transport barge driven by 27 tugboats, led by three guide ships.

An inscription from Hat-reign shepsut claims that Djehuty, Inspector of All Karnak Works, oversaw two more obelisks measuring 108 cubits high (56 meters) and plated totally in electro. Consider that the “unfinished” of Aswan, the world’s largest obelisk, stands 43 meters tall and weighs 1,260 tons.

THE PRIVATE ZONE OF GOD

An open-air patio follows the entrance pylon. It represents Re, the Sun’s apotheosis, with his victory over chaos and his opponent, the serpent Apophis, repeated each night, followed by fresh dawn.

There are two large sanctuaries here that served as resting spots for the Theban triad’s portable boats, including Amun, his wife Mut, and their son Khonsu. During the great festivals, the gods’ images were brought in boats during long processions, during which the pauses were utilized to provide repose to the divinities.

They were constructed under the reigns of Seti II (1200-1194 BC) and Ramses III (1200-1194 BC) (1184-1153 BC).

Following the conventional temple layout, we find a hypostyle or colonnaded room after the courtyard. The thicket of reed that surrounding the emergent hill of the Nun, the primal ocean, is depicted in this room.

The example of Karnak, whose construction dates from Seti I (1305-1289 BC), is breathtaking. The 134 papyriform columns in the room, which measures 103 by 52 meters, reach a height of 21 meters, with more than five meters in diameter, compared to 15 meters for the rest of the columns.

The contrast in height between the central and lateral columns allowed for huge stone windows, which were the only source of light. The kings of Thebes had their coronations in this room.

As we enter the temple, all we do is reenact the trek up the primordial hill from its base to its summit. As a result, we proceed through modest ramps and steps towards the sanctum sanctorum, the hill’s symbolic summit.

At the same time, the star-studded ceilings get lower and lower, reflecting that our ascent is taking us closer to the sky. Unfortunately, the core of the Amun temple in Karnak is not well preserved enough to discern this detail, which may be seen in later temples such as Edfu.

We arrive at the main sanctuary for his portable boat before heading to the god’s resting site. When Amun was not participating in the processions, he parked his portable boat here.

The nerve center of the temple grew beyond the sanctuary of the boat, where there is now just a wasteland: a dimly illuminated space, where a chapel or naos cut into a stone monolith housed the statue of Amun. Every day, all the doors leading to this room were closed and sealed, as no one was allowed to enter Amon’s domain.