In 1860, Auguste Mariette, then director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, was working in the Saqqara necropolis, some twenty kilometers from Cairo, a site that had been his new center of operations for some years.

There he had discovered a decade ago the serapeum, the burial place of the sacred Apis bulls, a labyrinthine space filled with gigantic stone sarcophagi that contained the mummies of these bovidae.

Mariette had just made another important discovery in the necropolis: A mastaba from the Old Kingdom, specifically from Dynasty III (2592-2544 BC), on the north face of the Step pyramid.

It was the grave of a man named Hesy-Ra, who lived during the reign of Djoser, the builder of the Step Pyramid. The archaeologist excavated the structure of the grave, made of mud bricks, and made a surprising discovery that he himself describes as follows:

“Hesy-Ra’s tomb is built of yellow bricks and the main chamber consists of a long corridor filled with niches rectangular. It was behind those niches that we found the tables …

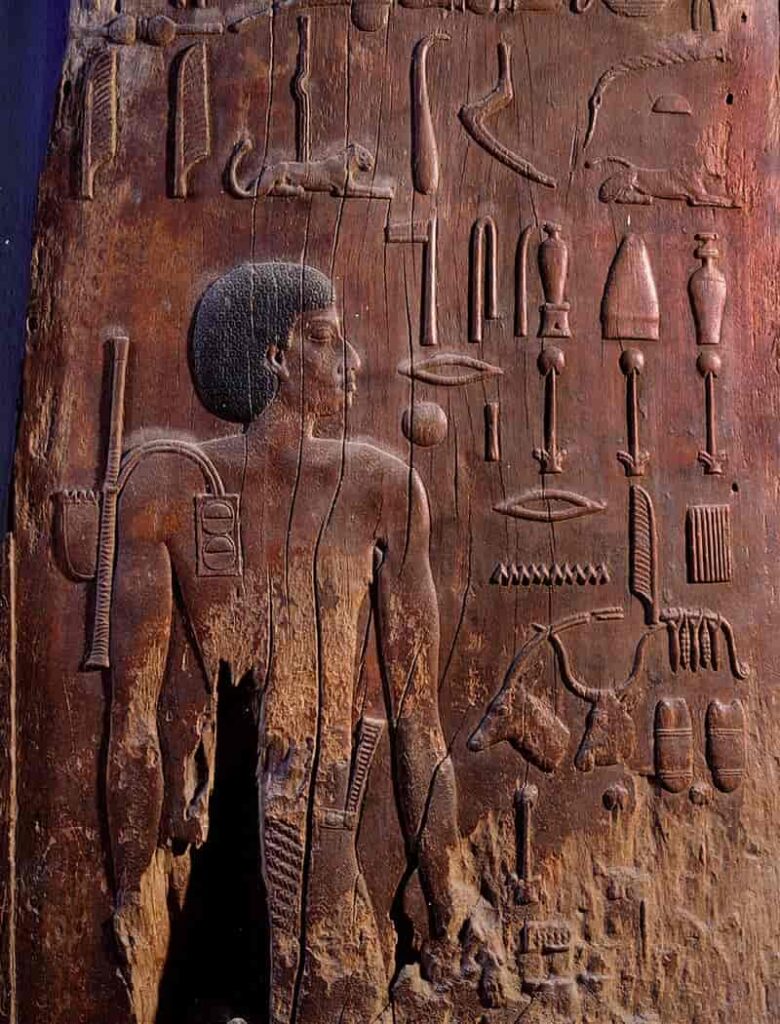

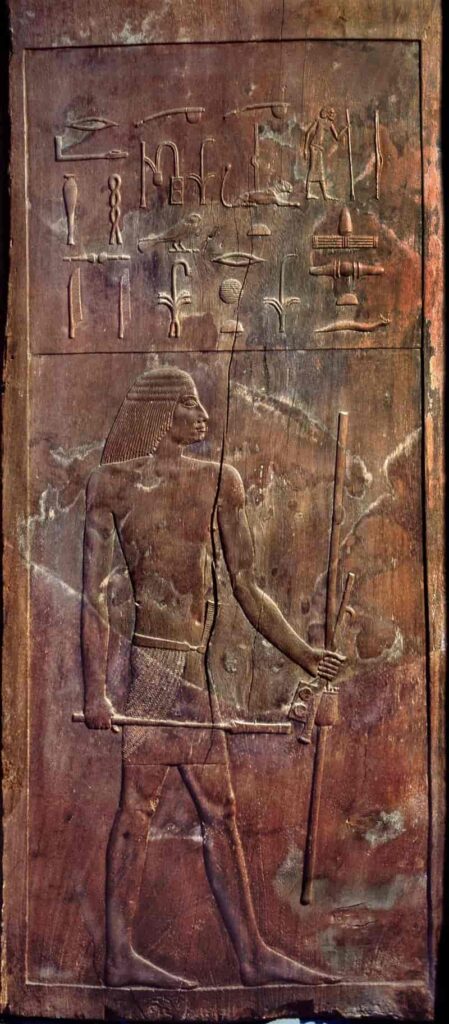

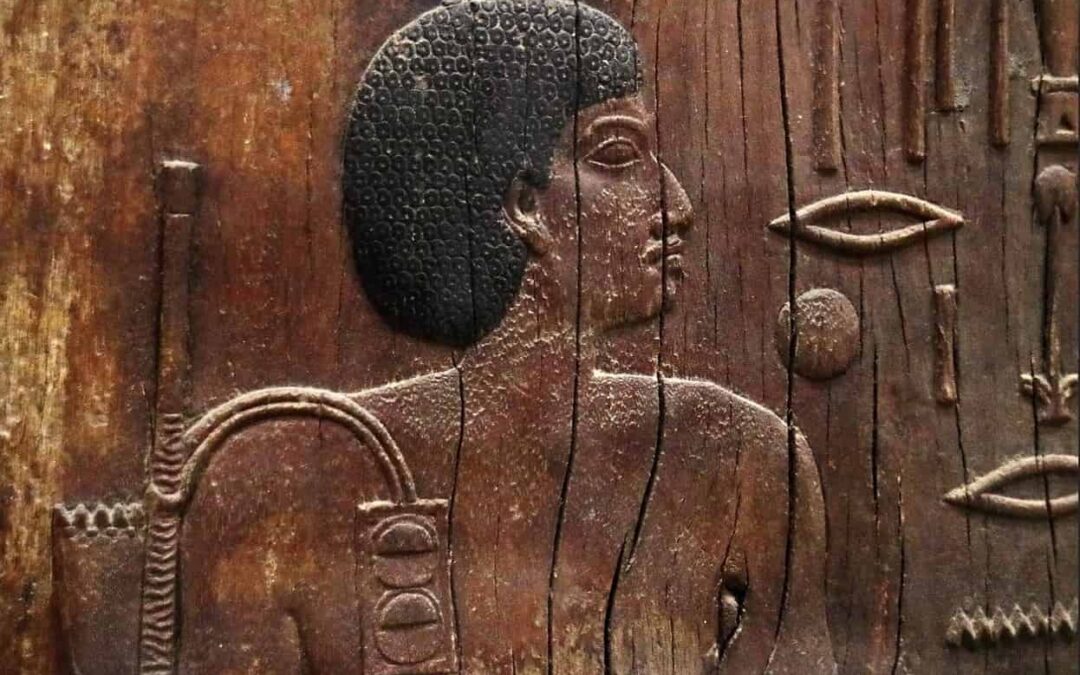

But what tables was Mariette talking about? In the course of his excavations at Hesy-Ra’s tomb, the archaeologist discovered five cedar wood planks decorated with magnificent reliefs measuring approximately one meter in height. The tables were extracted and taken to the Bulaq Museum in Cairo, antecedent to the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square.

Pictures on the walls

In the end, the location of Hesy-Ra’s grave was lost. After the excavation of a tomb, Mariette had the custom of reburying it to protect it from looters and onlookers.

Thus, this mastaba does not appear on the map of the necropolis that Jacques de Morgan, the new director of the Antiquities Service who succeeded Gaston Maspero, published in 1897.

The tomb was lost for years until between 1911 and 1912, the archaeologist James E. Quibell, who was excavating at the Saqqara necropolis at that time, returned to locate it. Quibell then proceeded to his excavation and study, and later published the exhaustive results of his investigations.

Hesy-Ra’s tomb is a mastaba or grave of considerable size (43 m long by 6 m high in some areas) and it was basically built with mud bricks.

What stands out in it, in addition to its early dating, is its decoration, of great artistic quality. The tomb consisted of a long, narrow corridor on the western side of which eleven niches were opened that once contained the famous wooden boards mentioned by Mariette.

He took five, who were at the southern end of the passage. During his excavations, Quibell discovered another table,very fragmented, on the north side, and decided not to recover another five due to their poor condition.

The walls of the tomb were decorated with geometric elements in bright colors. Quibell described the decoration in detail:

“There were no scenes of offering bearers, no images of these little explanatory texts on top, no figures of animals, or men, but a long succession of oblong frames placed on a matte surface”

In fact, both he and his wife made watercolors of these “pictures”, which had a very different character from the paintings that would decorate the walls of later tombs.

The tomb also contained underground chambers organized in three levels (the upper one was sealed with a sliding rock). However, it was not spared from looting already in ancient times, so there was very little that could be recovered from its interior.

Quibell documented some bones, ceramic remains, broken stone vessels, and a bone handle inscribed with Hesy-Ra’s name. The dating was confirmed by the presence of a clay seal on which the name of the pharaoh Netjerikhet-Djoser could be read.

Unique wood panels

As for the cedar wood planks decorated with reliefs found in Hesy-Ra’s tomb, although they are not the only ones of this type found in an Old Kingdom tomb, they are very rare. Why?

Although it may seem that the most probable cause that many of these panels were not found in tombs from this period is the destructive action of insects, especially the white ant, very abundant in Egypt, in reality the reason is basically the quality wood shortage in the country (which had to be imported), so this material used to be reused.

In fact, the wooden reliefs discovered in Hesy-Ra’s tomb can be considered masterpieces of their kind, for the quality of the carving and, above all, for their accuracy.

They show the owner of the tomb, the high official Hesy-Ra, represented at different stages of his life: as a handsome young man, a man in the prime of his life, and an old man seated at an offering table.

The panels also show several columns of inscribed hieroglyphic texts that refer to the owner of the tomb, and detail the titles and positions he held in life.

Among them stands out one, that of Wer-ibeḥsenjw, which means “Great ivory cutter” or “Great dentist”. Apparently Hesy-Ra was a man with great knowledge of medicine and dentistry.

In fact, he is the first documented dentist in all of history. A profession that must have been of great importance in ancient Egypt, since cavities and abscesses were common evils that affected royalty so much (the mummy of Amenhotep III showed a poor dental quality and that of Ramses II presented an abscess that perhaps cost his life) as the poorest of the peasants….

Source: Carme Mayans, National Geographic