In 1871, during excavations carried out by Auguste Mariette in the Meidum necropolis, the tomb of one of Pharaoh Khufu‘s brothers and his wife came to light.

Although the mastaba had already been looted in ancient times, it retained an impressive treasure that has become an icon of ancient Egypt: Two life-size statues of the owners of the tomb.

In 1871, Auguste Mariette, director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, was excavating at Meidum, about a hundred kilometers south of Cairo.

Meidum is famous for its truncated pyramid, most likely built by Pharaoh Sneferu, which stands in the middle of the desert landscape like a gigantic sunken tower.

But in Meidum there is also a vast necropolis of mastabas from the Old Kingdom (2543-2120 BC). And the excavation of some of these tombs, located to the north of the pyramid, is what Mariette and his team were busy with.

During the exploration of the place, near the mastaba of Nefermaat (one of Sneferu‘s sons), Albert Daninos, Mariette’s helper of Greek origin, coordinated a group of workers who were removing a stele.

When they completed their work, they found the entrance to a shaft that led into a gallery. Apparently they had just discovered a new mastaba.

Excited, Daninos commissioned one of the workers to enter the gallery with a candle for a preliminary inspection. Thus, armed with his flickering light, the man entered the gallery, not without some apprehension.

Daninos waited outside impatiently. After a while, the workman reappeared, in a hurry and with a look of terror on his face.Daninos explains why the man had been so frightened:

“The worker found himself in the presence of the heads of two living human beings whose eyes were staring back at him.”

A couple of lineage

In reality, and as we can all imagine, there was no one alive inside that mastaba (which would be known as number 6), nor had any evil spirit stared at the terrified worker.

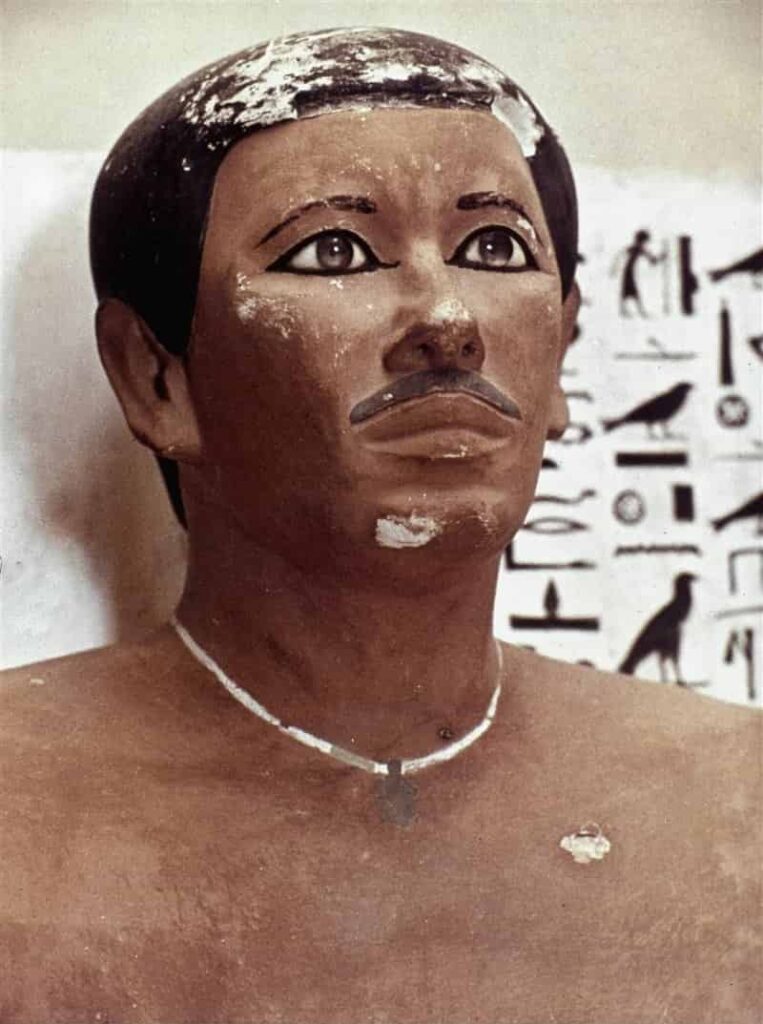

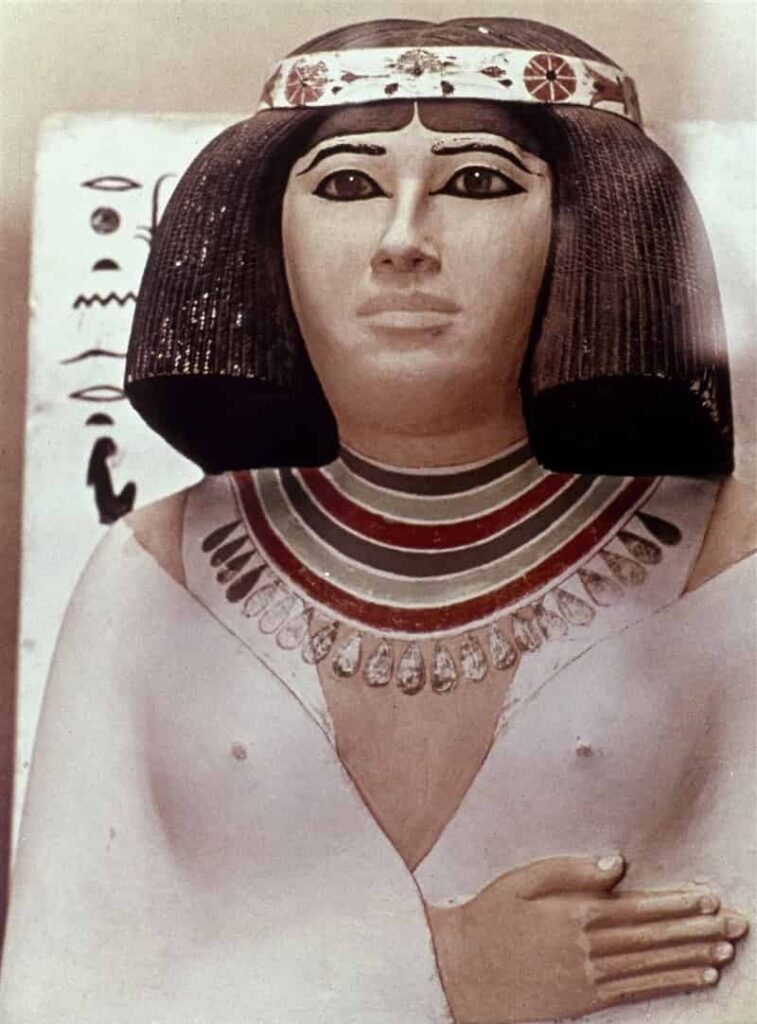

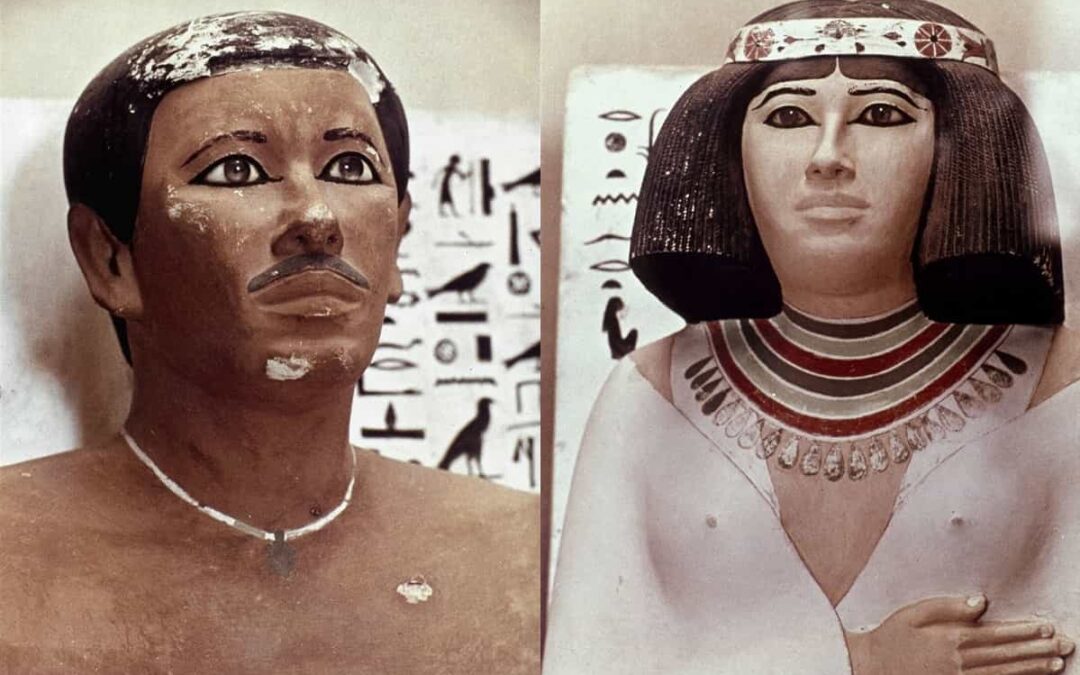

Those who had frightened the Egyptian worker in this way were two realistic funerary statues representing the owners of the tomb: Prince Rahotep and his wife Nofret (the magnificent pieces were transferred shortly after to the Bulaq Museum, in Cairo, antecedent to the current one).

But who were these illustrious characters? Apparently Rahotep was one of the sons of King Sneferu, the first pharaoh to have a smooth-faced pyramid built and also the father of Khufu, the owner of the Great Pyramid of Giza, and therefore Rahotep’s half-brother.

As a member of royalty, Rahotep held several important titles: High Priest of Ra, Chief of the Builders, Chief of the Royal Army, Director of Expeditions and, of course, “the son of the king, begotten in his body”.

For her part, Nofret (which means “the beautiful one”) held the title of Acquaintance of the King. From the inscriptions found inside their tomb we know that the couple had six children, three boys and three girls.

Apparently, Rahotep died young and because of his position he had been buried in a luxurious mastaba in the Meidum necropolis, near one of the pyramids raised by his father and next to the mastaba of his brother Nefermaat and his wife Itet (in this tomb would discover one of the most famous and beautiful paintings of Egyptian art: the frieze known as “the geese of Meidum”).

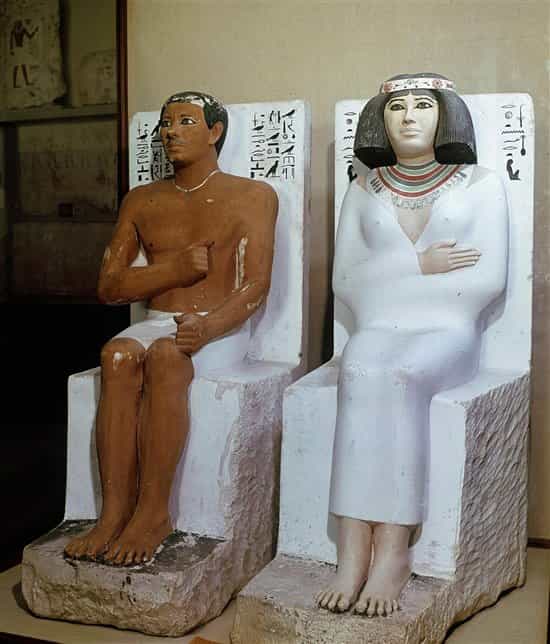

The statues representing Rahotep and Nofret are made of stuccoed limestone and round in shape, and today they are kept in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

These pieces have become great landmarks in the history of art for their great realism and formal perfection. The sculptures of the couple do not form a sculptural group, but are two individual statues that measure about 120 centimeters each and are represented in a seated position, on a kind of white painted throne where their names and titles have been written.

Both statues dramatically preserve the original polychromy and their eyes, made of white quartz and rock crystal, stare at the viewer. Both have the right hand flexed on the chest and the left on the thigh, in Rahotep’s case, with a clenched fist.

Rahotep wears a short white skirt and Nofret a tight sundress tied with a kind of cape, all white. Rahotep sports a fine, neat mustache and shaved cheeks, and a fine white pendant hangs around his neck.

For her part, Nofret is dressed in a short wig adorned with a diadem of rosettes and a wide necklace. They both have their eyes painted with kohl, they go barefoot, with their feet placed on a kind of footstool.

Nofret is shown as a lady of rank who is dressed in fashion. Rahotep, dressed simply, stands out above all for the firmness of his expression and gesture, and for his undeniable virility.

Hidden for all eternity

But oddly enough, these incredible statues were not intended to be admired by the viewer, as is the case today with any work of art.

In fact, they are two funerary sculptures designed not to be seen by anyone. Never. Their function was magical and they served so that the ka (one of the five parts that made up the soul of the deceased for the ancient Egyptians) could be incarnated in them in case the mummies were damaged or deteriorated.

In fact they had to remain hidden for all eternity, accompanying the embalmed bodies of the people they represented. But grave robbers and the passing of the centuries, as in so many other cases, made it impossible.

Source: Carme Mayans, National Geographic