The coronation of Ramses II was a lavish five-day ceremony intended to ensure the restoration of the balance of the universe, which was lost with the death of his predecessor, Seti I.

Danger Lurks

The body of Seti I was in the capable hands of the embalmers, whose task was to open the doors of immortality for the deceased pharaoh. Mummification allowed the sovereign to be reborn as Osiris, the god of the afterlife.

Now Ramses would ascend to the throne of Egypt as a new incarnation of the god Horus, son of Osiris, on earth. All the necessary actions following the death of the King were predetermined.

However, the disappearance of the monarch inevitably disrupted the cosmic order, known as Maat. Egypt was weakening, and as a result, hostile forces could pose a threat. These ranged from the enemies of the country to supernatural dangers that manifested as plagues, famines, and misfortunes, capable of plunging Egypt into chaos.

While the crown prince was undergoing all the required rites for his father, the pharaoh, to join the gods with whom he would reside for eternity, the coronation ceremony had not yet taken place.

Through this ceremony, the future sovereign would become the restorer and guardian of maat, thus restoring balance to the universe.

The Coronation of the New Pharaoh

To ensure the stability of the state and the natural order of Egypt during the transition from one reign to another, nobles, priests, and gods prepared the coronation of the new monarch, granting him the legitimacy to govern.

The ancient Egyptian texts relating to this ceremony are scarce, but they provide us with an insight into its proceedings. The coronation did not occur at a specific location, but each king selected a setting of special religious or political significance: Thebes, Memphis, Heliopolis, Sais, and more.

Apparently, the Egyptians preferred conducting the coronation on the first day of the new year or the first day of the peret season (the planting season, between November and March). The rites commenced at dawn on the first day and extended for a minimum of five days.

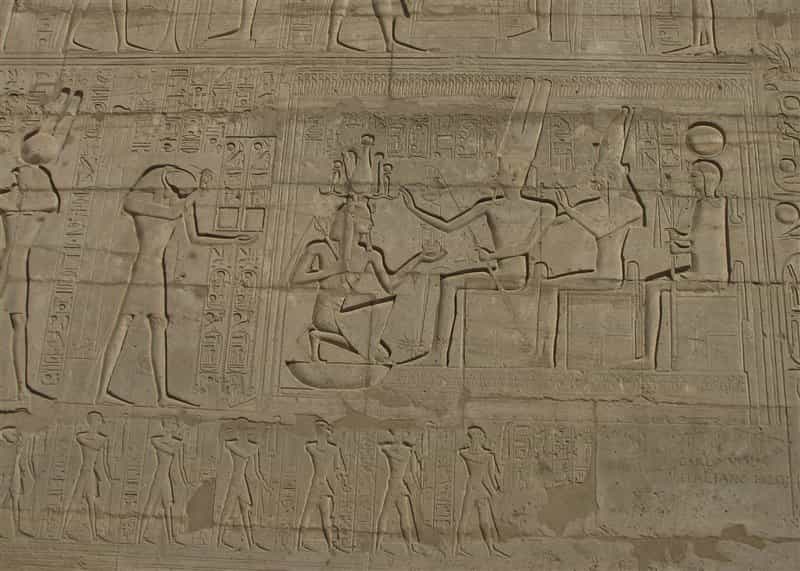

All the rituals took place within the temple and commenced with a ceremonial bath aimed at purifying the future king. Amidst hymns and praises, two priests adorned with falcon and ibis masks (representing the gods Horus and Thoth, respectively) performed this form of “baptism” by pouring water from the Nile onto Pharaoh, purifying him of human impurities.

Following that, the new king was anointed with seven sacred oils that offered protection against evil and connected him to magical substances: festival perfume, sacred oil, resin, nekhnem oil, uaut oil, premium cedar oil, and Libyan oil, all derived from the primordial earth that birthed the world. The bath with water from the Nile, the source of life, and the application of sacred oils served a twofold purpose.

Firstly, to establish the conditions of a birth that would open the doors to a new existence for Ramses (of a divine and powerful nature) as the sovereign of Egypt.

Secondly, to unite the new king with the very origins of the world and the cosmos. Lastly, another stage of the coronation involved a ceremonial race around a wall or a designated plot of land marked by milestones, symbolizing the “white wall” that encircled Memphis, the initial capital of Egypt, and representing the territory over which he would govern. Through this race, the new monarch consecrated his dominion over the country and bestowed his protection upon it.

New Names of the new pharaoh

As the sovereign embarked on a new existence, it was necessary for him to be bestowed with new names. Similar to all children in ancient Egypt, he had already been given a name upon his birth. However, the kings assumed five names, preceded by titles that connected them to divine concepts.

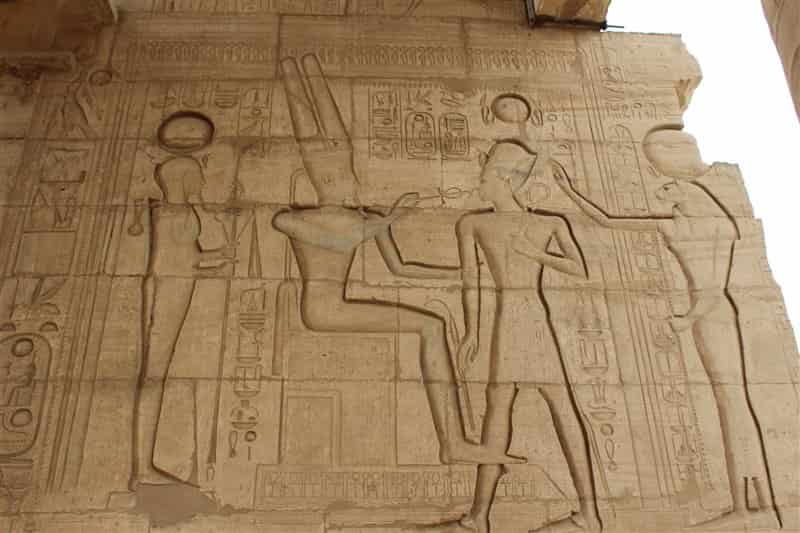

Once the names were bestowed upon them, and mirroring the nourishment of children after birth, the future king had to be nourished with mother’s milk. However, he magically derived sustenance from the breast of a maternal goddess, through whose milk he acquired divine qualities.

This goddess could be Isis or one of the various aspects with which this divinity was associated at certain times: Nekhbet, Uerethekau, Mut, Hathor, and more.

Royal Crowns of the Pharaoh

It was essential for the pharaoh to fulfill the coronation rites in a dual manner, once as the king of Upper Egypt (the territory to the south of Memphis) and another time as the sovereign of Lower Egypt (the country extending to the north of that city).

While seated on a dais, he was adorned with royal crowns, possibly offered by the gods Horus and Seth, representing the north and south respectively, followed by the presentation of scepters.

For instance, during Queen Hatshepsut’s coronation ceremony, the crowns were imposed on the sovereign in the following order: first, the nemes scarf; then the khepresh ceremonial helmet; next, the ibes headdress, and finally, one after the other, the red crown, the atef, the hennu, the crown of Ra, the white crown, and the double crown.

Among all the crowns, the most significant ones were the red, the white, and the double crowns, imposed on the new monarch by the god Atum, represented by a priest wearing the god’s mask. As the king of the north, he was dressed in the Per-ur chapel, known as “the big house,” with the red crown, protected by the cobra goddess Wadjet.

Right after that, as the king of the south, the sovereign was granted the white crown or pschent in the Per-neser chapel, called “the house of the flame,” associated with the vulture goddess Nekhbet.

We know that both crowns were in use since the 4th millennium BC and that, beyond their political significance, they held other connotations: the red one symbolized the feminine potential of life, while the white one represented the masculine vital principle.

The fusion of the red and white crowns gave birth to the double crown, which starting from the Tinite period in the 3rd millennium BC was used to signify the king as the ruler of unified Egypt. The Egyptians referred to it as sekhemty, meaning “the Two Mighty Ones.”

Depending on whether they wanted to emphasize his role as the ruler of Upper or Lower Egypt, the red crown was placed upon the white one or vice versa. This double crown was associated with the king’s earthly power, in contrast to the atef crown, which was linked to the world of the afterlife as the crown of Osiris.

Egypt Has a New Pharaoh

Once the coronation rituals are concluded, the envoys depart to all corners of the country to proclaim the names and titles of the new monarch, which must now be included in official documents.

Ramses, now a sovereign, faces a daunting task ahead as he assumes multiple roles, just like his predecessors. He will serve as a ruler, a high priest overseeing all the temples, a strategist, and a soldier. These responsibilities are ones he has been preparing for over an extended period, spending years as his father’s co-regent.

He will devote himself to these duties passionately, even though it means relegating his private life to the background. In fact, he will dedicate the sixty-six years of his reign, one of the longest in the history of the Nile country, to the prosperity and greatness of Egypt.

Source: Elisa Castel, National Geographic