In 1929, American Egyptologist Herbert E. Winlock uncovered a fascinating discovery beneath Queen Hatshepsut’s temple in Deir el-Bahari. This find was the tomb of another queen from the early 18th Dynasty, which had been plundered in antiquity but later “restored” and reburied with reverence by the priests of the 21st Dynasty, albeit for a fee.

Almost a decade after the notable discovery of Meketre’s tomb, an esteemed official of the Eleventh Dynasty, Winlock was back in Deir el-Bahari in January 1929, continuing his work around the grand funerary temple of Queen Hatshepsut.

His team was engaged in clearing debris from the temple’s hillside when they noticed two piles of fragments, potentially from a previously undiscovered tomb. Acting on this lead, they continued their excavation.

On February 23, Winlock recorded in his diary the discovery of a hole in the rock, which turned out to be the entrance to a tomb featuring two distinct burials from different eras.

The first burial was that of Nauny, a member of the 21st Dynasty (1069-945 BC), who was a King’s Daughter and the offspring of Pinedjem I. The second burial, located at the back of the tomb through a long corridor and burial shaft, belonged to Queen Ahmose-Meritamun from the early 18th Dynasty (1550-1295 BC), the original occupant of the tomb.

Two Women from Different Eras

The tomb unearthed by Herbert E. Winlock contained the remains of two women from distinct periods, each with its own intriguing backstory.

Nauny, whose burial was much later than Ahmose-Meritamun’s, was interred in a coffin adorned with yellow paint and floral garlands, indicating an “intrusive burial” from a subsequent era.

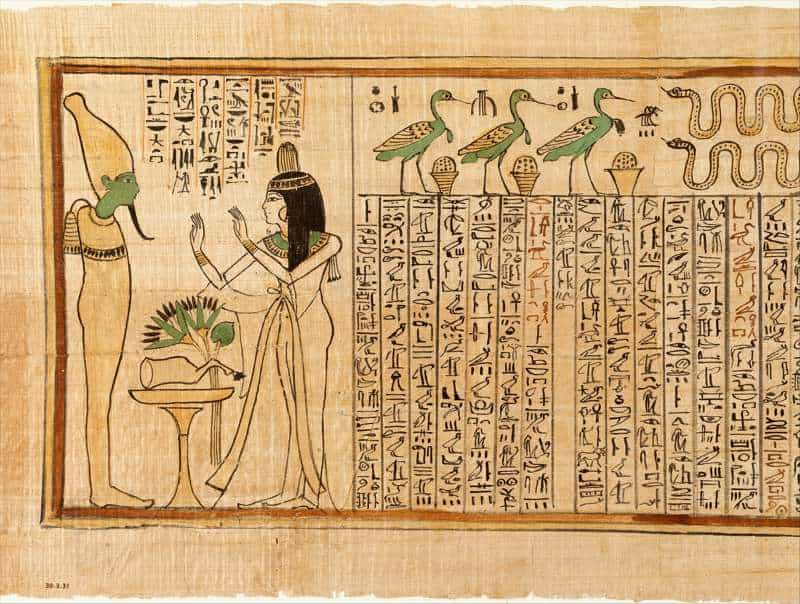

Surrounding her were multiple ushabti figurines and a hollow representation of Osiris, which contained a rolled papyrus featuring a version of the Book of the Dead. Despite these notable items, archaeologists did not find Nauny’s burial particularly remarkable.

In contrast, Queen Ahmose-Meritamun, who was both the sister and wife of Amenhotep I, was a member of the early 18th Dynasty. Her lineage included her father Ahmose, the Pharaoh who defeated the Hyksos, and her mother, Queen Ahmose-Nefertari.

Winlock was deeply moved by the discovery of Ahmose-Meritamun’s tomb, reflecting in his journal on the profound atmosphere of the site: “The silence, the darkness, the knowledge that this sarcophagus had remained there for centuries […]. All this combined in an atmosphere of mystery; this situation did not occur every day.”

The queen’s burial was of exceptional quality. She was entombed in two wooden coffins. The outer coffin was notably large, over three meters tall, and decorated with vibrant polychrome artistry, capturing her youthful, serene beauty.

In contrast, the inner coffin was smaller, measuring about 1.80 meters, and less elaborate. Inside, the queen’s mummy was found adorned with garlands so fresh that the colors were still vivid.

Yet, some inconsistencies raised questions. Despite the tomb’s seemingly intact condition, the furnishings were minimal and of inferior quality, consisting mainly of simple baskets filled with debris.

Additionally, the outer coffin had originally been decorated with colored glass and gold leaf, but these materials had been replaced by paint. The reason for this alteration, and who carried it out, remains a mystery.

The “Restored” Queen

The enigma surrounding the tomb of Ahmose-Meritamun was unraveled with the discovery of a label on her mummy’s shroud, inscribed in hieratic script: “Year 19, third month of the season of Akhet, day 28. On this day the inspection of the King’s Wife, Ahmose Meritamun.” This inscription provided a crucial clue.

Winlock uncovered that this was a gesture of preservation. During the 21st Dynasty, priests undertook the task of recovering numerous royal mummies from their desecrated tombs—such as those found in the Deir el-Bahari cache in 1881—to protect them from the rampant thefts in the Valley of the Kings. In the process of “restoring” these mummies, they encountered the tomb of Ahmose-Meritamun, which had been thoroughly plundered.

Although the priests rewrapped the mummy and reburied it with care, their actions were not entirely altruistic. The “inspection” involved stripping the mummy of its jewelry and removing the gold leaf and colored glass from the outer coffin. This act of desecration was thus not the work of common grave robbers.

Further investigation revealed that Masaharta, the high priest of Amun and son of Pinedjem I, was behind the vandalism. Under his stewardship, many royal mummies were relocated for purported protection.

It became evident that the wealth still associated with these mummies likely served Masaharta’s political ambitions, demonstrating how the restoration efforts were tainted by personal gain.

Source: Carme Mayans, National Geographic.