The year was 1274 BCE and a god was on the march. Standing six-feet tall with a square jutting jaw, thick lips and a long sharp nose, Ramesses II rode his golden chariot ahead of an army of 20,000 archers, charioteers and sandalled infantrymen.

Only five years into his reign as pharaoh, he had already established himself as a fierce warrior and strategic military commander, the rightful blood heir to the newly established 19th Dynasty and a true spiritual son of the goddess Isis herself.

Ramesses’ soldiers would have seen their commander-in chief as the rest of Egypt did: as a god in the flesh possessed of legendary strength and bravery, incapable of error and on a divine mission to re-establish Egypt as the dominant superpower of the Middle East.

The mighty Ramesses II: Battle of Kadesh

Ramesses’ destination was Kadesh, a heavily fortified Syrian city in the Orontes River valley.

Kadesh was an important centre of trade and commerce and the de facto capital of the Amurru kingdom, a highly coveted piece of land sandwiched on the border between the Egyptian and Hittite empires.

As a boy, Ramesses had ridden alongside his father Seti I, when the elder Egyptian king finally wrested Kadesh from the Hittites after more than half a century of abortive attempts.

But as soon as Seti returned victorious to Egypt, the scheming rulers of Kadesh re-pledged their allegiance to the Hittites.

Ramesses had returned to Syria to salvage two tarnished reputations: his father’s and that of his previously great empire. Ramesses and his army had been marching for a month.

They departed from the pharaoh’s royal residence along the eastern edge of the lush Nile Delta in April, cutting across the Sinai Peninsula, following the curve of the Mediterranean coastline up through Canaan, past the strategic highland outpost of Meggido, into the fertile valleys of Lebanon and finally arriving in the forests outside Kadesh.

The pharaoh’s scouts fanned out to assess the enemy’s preparations for battle. The locals painted a deceptively favourable picture.

The Hittite king Muwatalli was so afraid of the great Ramesses and his legendary charioteers that the Hittite army was biding its time a hundred miles away.

Ramesses had been living the life of a god for so long that perhaps he believed a little too much in his own divine intimidation.

While still an infant, his grandfather helped forge a revolutionary new dynasty in Egypt, one based on military might and absolute royal authority.

Ramesses II: Family

Ramesses’ grandfather was born Paramessu, a foot soldier who had worked his way up to general in the Egyptian army. He found favour with Horemheb, another lifelong military man who had become pharaoh after the untimely death of the teenage king, Tutankhamun.

Horemheb, who had no sons of his own, saw a disciple in Paramessu, someone who would carry on his aggressive campaign of brutal subjugation of rebellious tribes in Nubia, Libya and distant Syria in the name of strengthening the kingdom.

When Horemheb died, Paramessu ascended the throne and changed his name to ‘Ramessu beloved of Amun,’ the man history knows as Ramesses I.

From birth, Ramesses II was groomed to be pharaoh. His father Seti I inherited the throne 18 months after Ramesses I became king and his son was raised in the lavish royal palaces of the pharaohs, waited upon by nurses and handmaids and trained by tutors in writing, poetry, art and, most importantly, combat.

Seti named Ramesses the commander-in-chief of the army when the boy prince was only ten years old. At 14, Ramesses began to accompany his father on military campaigns and witnessed the overwhelming power of the Egyptian charioteers in combat on more than one occasion.

Now he was no longer a boy watching such campaigns but a man – a god – leading them. He was an hour’s march from Kadesh and heartened to hear his enemies were rightfully trembling at his godly might.

What happened in the Battle of Kadesh?

Ramesses ordered his troops to make camp. The royal tents were raised, the horses watered at a gentle tributary of the Orontes, and the soldiers circled the chariots as a half-hearted barricade against the unlikely possibility of attack.

In reality, an attack was not only likely, it was imminent. It turned out the locals rounded up by the Egyptian scouts were planted by the Hittites.

King Muwatalli and his large force of Hittite charioteers, archers and infantrymen were camped on the far side of Kadesh, hidden from view in the river valley. Luckily for Ramesses, a second wave of Egyptian scouts captured a pair of Hittite spies and beat the truth out of them.

Muwatalli was planning an ambush. The target wasn’t Ramesses’ camp, but the legions of unsuspecting Egyptian infantrymen still marching.

Ramesses dispatched his speediest messengers to warn the approaching troops, but it was too late. Thousands of Hittite charioteers descended upon the unprotected infantry.

The Hittites rode three to a chariot: one driver, one archer and one spear-wielding warrior to cut down foot soldiers at close range.

They wore ankle-length chain-mail armour, while the Egyptian infantry were naked to the curved blades of the Hittite scimitars.

The heavy chariots ploughed through the ranks, littering the hillside with corpses and sending the survivors fleeing for Ramesses’ camp.

What happened next says more about Ramesses II than perhaps any other event in his long reign as pharaoh.

The Hittite forces pursued the decimated Egyptian army all the way to Ramesses’ camp, crashing easily through the porous Egyptian defences and battling their way toward the royal tents themselves.

Then, according to a first-hand account known as the Poem of Pentaur, Ramesses emerged from his tent and single-handedly faced down the enemy hordes: “Then His Majesty appeared in glory like his father Mont, he assumed the accoutrements of battle, and girded himself with his corslet, he was like Ba’al in his hour.”

This was the moment that saw the birth of Ramesses the Great.

The pharaoh took to his chariot and sliced through the Hittite ranks, cutting down the foe with his bow while rallying his troops to battle.

The image of Ramesses on his golden chariot — his bow drawn back in deadly fury, his wheels rolling over the crushed bodies of his enemies — is carved into the walls of more Egyptian temples than any other story in the empire’s 3,000-year history.

If you believe the Poem of Pentaur, which adorns the walls of temples at Luxor, Karnak, Abu Simbel and more, then King Muwatalli was so cowed by Ramesses’ superhuman strength that he immediately petitioned for surrender.

But is that really how the Battle of Kadesh went down? Do historians believe the account of the Poem of Pentaur, that a single man defeated an entire Hittite army? Hardly.

Why was Ramesses the Great so great?

Ramesses the Great, most Egyptologists now believe, deserves his title not for his heroics on the battlefield or his potency as a patriarch – he allegedly fathered well over 100 children – but for his flair for propaganda.

Ramesses was, quite literally, the greatest image-maker of antiquity.

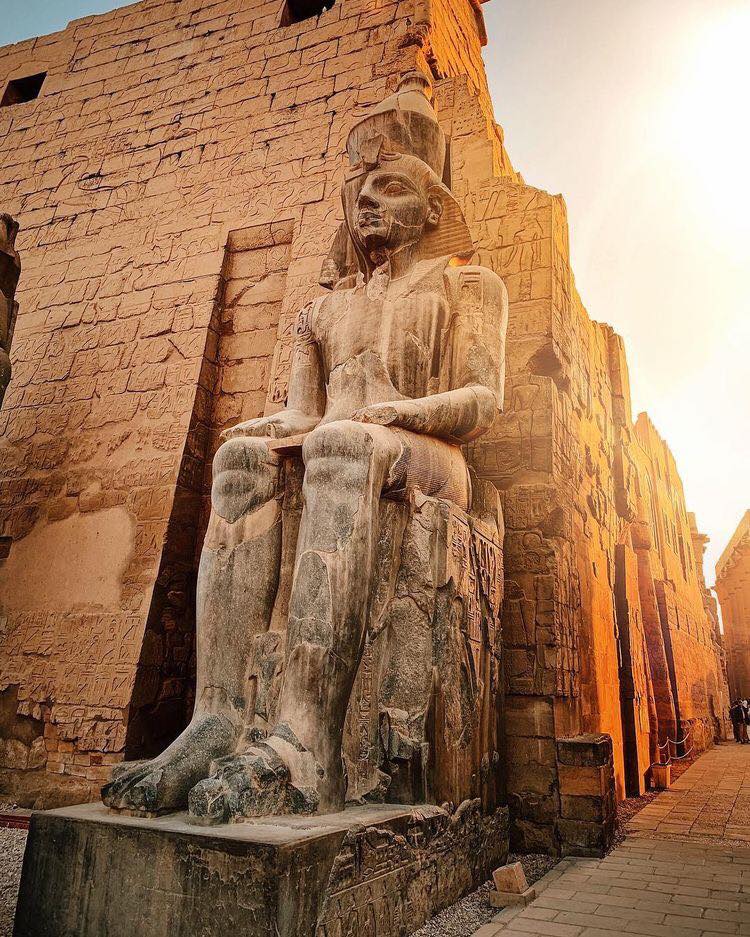

Those visiting the ruins of the great Egyptian temples today are sure to find themselves in awe of a seated stone statue of Ramesses II guarding the gate, or a series of identical Ramesses sculptures supporting interior pillars.

To everyday citizens staring up at his colossal and unblemished image, they would have no choice but to believe the statue’s unspoken message: here stands your king, your ruler, your god.

What’s more, Ramesses ruled as pharaoh for a staggering 66 years. His reign spanned several lifetimes for the average Egyptian, reinforcing the idea that his rule really was eternal.

The sheer length of his reign largely accounts for the grand scale of his construction projects and the ubiquity of his image.

The ancient pharaoh Khufu was only king for 23 years and he built the Great Pyramid at Giza. Imagine what Ramesses was able to accomplish in 66.

What is Ramesses II best known for?

To understand the impressive scope of Ramesses’ architectural vision, we only have to look to the royal city that bore his name, Per-Ramesses, or Piramesse.

Located 120 kilometres (75 miles) from modern-day Cairo, Piramesse began as a humble summer palace built by Ramesses’ father Seti I near the family’s ancestral home on the eastern edge of the Nile Delta.

Over the course of 18 years of construction and expansion, Piramesse became the third-largest religious centre of Egypt — next to Memphis and Thebes — and the political capital of the entire empire.

Very little of Piramesse’s grandeur remains today, but first-hand accounts describe a city of incomparable beauty and wealth.

The Royal Quarter sat on a hill overlooking the Nile. Streets lined with royal residences and temples, ten square kilometres (four square miles) of towering columns, expansive courtyards and stairways encrusted with multicoloured tile work.

The empire’s wealthiest families, government officials and high priests lived in surrounding villas connected by canals and lush water gardens.

The farmland encircling the city was some of the most fertile and productive in the region, supplying Piramesse with ample grain, fruits and vegetables to feed its 30,000 citizens and fill the pharaoh’s ample storehouses.

Piramesse was also a striking, cosmopolitan capital. Ramesses likely chose the city’s location for its proximity to the fortress at Sile, the traditional gateway to the eastern provinces of Palestine, Syria and the Asiatic empires beyond.

Foreign diplomats, traders and migrant labourers arrived at the newly built capital in droves.

In addition to the traditional Egyptian temples built to Seth and Amun, there were foreign cults dedicated to Ba’al, Anat and the Syrian goddess Astarte, whom the pharaoh adopted as the patron deity of his chariot horses.

The pharaohs of Ancient Egypt were more than mere figureheads: they served multiple roles as religious leaders, military generals and political rulers.

The pharaoh’s ultimate responsibility was to lead the empire toward ma’at, the ideal state of cosmic harmony, justice, order and peace.

The Egyptians were skilled astronomers and charted the orderly and predictable movements of celestial bodies, each connected with a god or goddess.

The goal of individual human beings and Egyptian society as a whole was to reflect the divine harmony of the heavens on Earth.

The pharaoh, through his legal, religious and military roles, exerted the greatest influence of all. In that sense, Ramesses was indeed a great pharaoh.

The Egyptian empire enjoyed a prolonged period of stability and ma’at under his watch.

For all of his posturing as a superhuman warrior who crushed his enemies by the hundreds of thousands, Ramesses was in fact a savvy military and political strategist. The historically dubious Poem of Pentaur is not the only document of Ramesses’ greatness.

What was the treaty signed between Egypt and the Hittites? Why was it important?

Hanging in the hallways of the United Nations building in New York City is a clay replica of the world’s first peace treaty, signed in 1269 BCE by the Hittite King Hattusillis III and Egypt’s very own Ramesses II.

But was this the peace treaty the Hittites begged Ramesses to sign after his brutal show of strength during the Battle of Kadesh? Not at all.

The true outcome of the Battle of Kadesh was a blood-soaked stalemate. Ramesses was saved from the Hittite chariot ambush by the arrival of reinforcements from the sea.

The Egyptians pushed the Hittites back across the Orontes, but both sides lost so many men in the slaughter that both kings lost their appetite for the main event.

Ramesses returned to his native Egypt with nothing to show for a monthslong military campaign.

A decade later, and the pharaoh once again looked to prove his power by driving his forces to the north to test the strength of Amurru and Kadesh.

This time, the Hittite King Muwatalli was dead and the Hittite empire was in the throes of a succession crisis.

Ramesses easily took the city and claimed Amurru for Egypt. Expecting a full-scale reprisal by the Hittites, Ramesses was instead greeted by a cadre of Hittite diplomats.

The new King Hattusillis had more to worry about than an Egyptian pharaoh with an old vendetta. The Assyrians to the east had amassed wealth and political might that threatened to crush any single empire that stood in its way.

But together, Hattusillis proposed, the Hittites and Egyptians could defend their sovereignty. The peace treaty hanging in the UN is a testament to Ramesses’ long-term political vision. He could easily have viewed Hattusillis’ offer as a sign of weakness and attempted to rout the Hittites once and for all.

Instead, he saw an opportunity to drop a centuriesold feud that cost Egyptian lives and resources and engaged in an unprecedented act of diplomacy that would bring peace and stability to the kingdom for generations to come.

To seal the newly brokered relationship between the Hittites and Egyptians, Ramesses accepted one of Hattusillis’ daughters as his seventh principal wife.

Back in Piramesse, the royal capital, the new Hittite allies proved invaluable to the strengthening of the Egyptian armed forces.

The capital city was more than a showcase for the prosperity of the empire.

It also housed the pharaoh’s largest armoury, a massive bronze-smelting factory whose blast furnace provided the swords, spears and arrowheads for Egypt’s army.

Shortly after the peace treaty was signed, Ramesses imported Hittite craftsmen to instruct the armoury workers in the secrets behind their impervious Hittite shields.

The Egyptians may have lost an enemy in the Hittites, but there were plenty of aggressors itching to take their place.

Until the very end of his reign, Ramesses vigilantly defended Egypt’s borders against threats from Libyan tribal leaders, Assyrian raiders and more.

Ramesses’ power

Ramesses’ power was about much more than military might, though; he was a god among men.

To understand his significance as a religious leader, it is important to understand how the Ancient Egyptians viewed the universe.

From its earliest beginnings, Ancient Egyptian religious worship centred on a deeply held belief in the afterlife.

In fact, the concept of ma’at originated with the ostrich-winged goddess Ma’at who ‘weighs’ the hearts of the deceased to determine their worth.

The dozens of other gods and goddesses in the Egyptian pantheon – Ra, Osiris, Amun, Isis, Seth and many more – each played a role within a complex mythology of creation, death and rebirth.

To the average Egyptian citizen in Ramesses’ time, the gods were responsible for the orderly function of the universe and offered personal protection and guidance on the mysterious journey from life to the afterlife.

Egyptians expressed their gratitude and devotion to the gods through the celebration of seasonal festivals and by bringing offerings to the gods’ temples.

The pharaoh, of course, was not your average Egyptian. The royal cult was deserving of its own worship.

Ramesses was the intermediary between the divine and the human. While living, pharaohs were the sons of Ra, the powerful Sun god.

In the afterlife, pharaohs are the offspring of Osiris. In a competing cosmology, pharaohs are the living incarnation of Horus, the son of Isis.

In any case, the implications are clear. The pharaoh is the earthly link to an unbroken line of divine authority, stretching from the very creation of the universe itself to the eternities of the afterlife.

The government of Ancient Egypt was a theocracy with the pharaoh as absolute monarch. But that doesn’t mean that Ramesses personally oversaw each and every aspect of Egyptian civil life.

His chief political officers were two viziers, one each for Upper and Lower Egypt.

Serving as chief justices of the Egyptian courts, viziers conducted the tasks of collecting taxes, managing the grain reserves, settling territorial disputes and keeping careful records of rainfall and the Nile’s water levels.

Treasurers managed the finances of state, as well as running the stone quarries that built national shrines.

If an average Egyptian had a grievance, he would take it up with the local governors in charge of each of Egypt’s 42 nomes – or states. Governors reported to the viziers, who met daily with the pharaoh for counsel.

During his long life, Ramesses renovated or constructed more temples than any pharaoh in all 30 Ancient Egyptian dynasties.

He also placed his figure prominently inside each and every one of them, often on equal footing with the gods. At first, this appears to be an unparalleled act of hubris.

But seen through the lens of the Egyptian religious mind, this spiritual self-promotion starts to make sense. If the highest goal of Egyptian civilization is to achieve ma’at or divine harmony, then you need a supreme leader whose very will is in absolute harmony with the gods.

Through his numerous construction projects, Ramesses proved his devotion to the gods while also nurturing his own thriving cult of personality.

Ramesses built some truly refined and subtle temples, especially his small addition to his father Seti I’s monumental temple complex at Abydos.

But refined and subtle was not in his nature. For starters, he liked to do things quickly.

In traditional temple construction, all decorative motifs on the outside of a temple were hewn using incised relief, in which images and hieroglyphs are carved into the stone to accentuate the contrast of sun and shadow.

In the darkened interiors of temples, however, artists used the more time-consuming bas-relief method, in which drawings and symbols are raised relative to the background.

In the interest of time, Ramesses ordered all of his temples to be etched in incise relief inside and out. That’s one reason why Ramesses built more temples than any king before or since.

Critics of Ramesses’ theatrical and self congratulatory construction style have irrefutable evidence in the two temples at Abu Simbel.

Both structures are carved directly into the living rock on a sheer cliff overlooking a switchback curve in the Nubian Nile.

Ramesses dropped all pretence of piety with the construction of the larger temple at Abu Simbel, which is appropriately called the Temple of Ramesses-beloved-of-Amun.

Four monumental statues of Ramesses – each more than 21 metres (70 feet) tall – guard the entryway to the grand temple. Inside of it, each wall bares some reference to the great pharaoh Ramesses.

Every pillar in the great hall is carved with Ramesses in the form of Osiris. Wall reliefs recount Ramesses’ heroic military exploits.

And deep in the Holy of Holies sit the three most revered creator gods of the Egyptian pantheon – Ptah, Amun and Ra – next to the deified image of Ramesses himself. In his day, Ramesses was arguably the most powerful man to walk the Earth.

He was the divinely ordained ruler of a thriving and cohesive civilization that was centuries ahead of its time.

As pharaoh of Egypt, he over-achieved in every category: crushing foreign enemies in battle, maintaining domestic order within his kingdom, building massive monuments to the gods throughout Egypt and preserving his own glorious legacy until his death.

As long as his stoic stone visage crowns the ruins of his magnificent kingdom, the greatness of Ramesses will continue to echo loudly through the ages.