One of the most persistent fantasies about ancient Egyptian sculpture is that it presented people as they actually appeared. There are various sinister theories—related to eugenicist comparison of ‘races’—that underlie this assumption; these require separate discussion.

Suffice it to say here that in no way were Pharaonic statues intended to be mimetic likenesses of living people. In an important sense statues were three-dimensional hieroglyphs, showing the essential components of a person in order for the statue to function as a vessel for a god, king, or non-royal person for eternity. Neither were statues simply ‘commemorative’ in the modern Western sense.

Yet statues are special. While they can personify ideas (and ideals), they take the form of people. And we find the human form—especially the face—particularly alluring. Egyptologists have been fascinated by the faces of Pharaonic sculptures to the detriment of understanding the functions of statues in context.

The ancient Egyptians did not—as far as we can tell— have public spaces as in Greece and Rome in which statues were displayed.

Statues were chiefly restricted to (elite) tomb and temple spaces, the latter only open to properly purified and initiated people. Regular contact with statue forms was a privilege.

Egyptian statues required a ritual known as the ‘opening of the mouth’ to activate them for use by a spiritual entity. Yet they were also routinely adapted, reinscribed, reused, deactivated, damaged, destroyed—and then reactivated all over again.

They offer an object lesson in the dynamism of sculpture, a set of lessons that many in the West may not have considered given our detached attitude to the sculpted form.

Take two examples of Pharaonic sculptures in the form of a sphinx; a hybrid lion-man, with leonine body and the head is almost always of the king (sometimes a royal woman) wearing a royal headdress.

The first (above) belongs to the 18th-Dynasty female pharaoh Hatshepsut (ca. 1473–1458 b.c.). As a sculptural statement of super-human power, the form was favoured by Hatshepsut perhaps because it offered a way to obscure her female sex and make her at once more ‘kingly’—and divine.

Yet, at some point attitudes to her changed. This sculpture, like countless others, was dragged out of the queen’s impressive temple at Deir el-Bahari, hacked up into hundreds of pieces and flung into a pit—almost as much work as carving and installing the sculpture itself—only to be discovered by Egyptians working for an expedition of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in the early 20th century.

Hatshepsut’s various sculptures were painstakingly pieced back together, with the restorers making judicious restorations to elide the extensive damage, with the results exhibited today as great works of ancient sculpture.

The destruction of Hatshepsut’s statues was not the result of popular protest against her rule (as some early, misogynist commentators supposed of a powerful female ruler); rather, it was a ritual requirement, to remove her presence from the temple and refocus its ritual energy on another king.

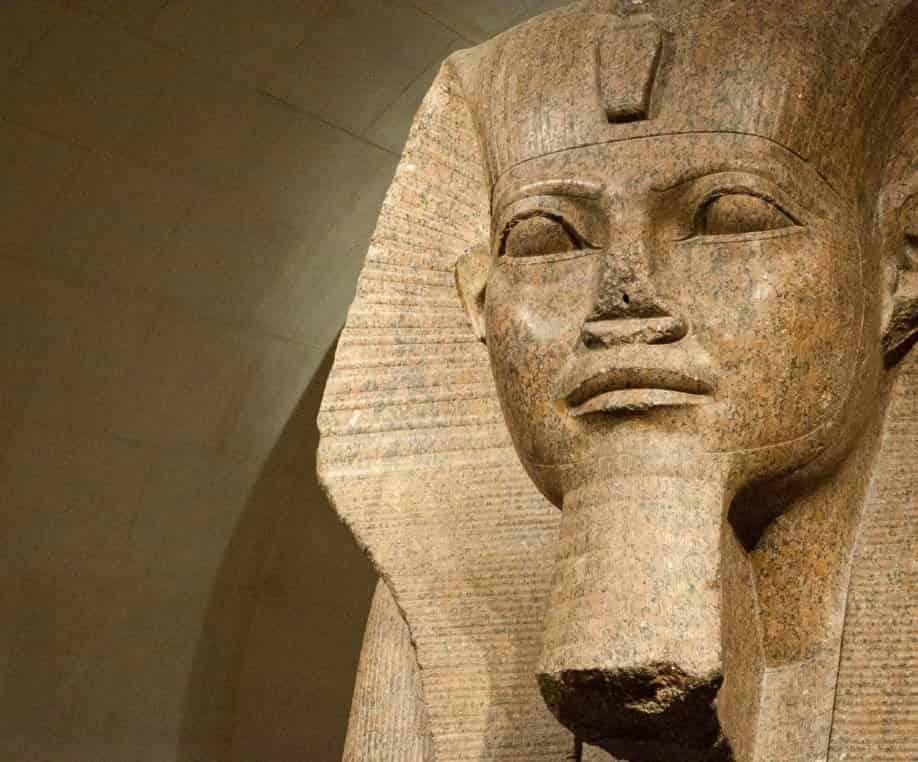

Compare that with another imposing, maned sphinx (above), originally carved perhaps some 500 years before Hatshepsut. This example also sports a royal headcloth, and the features of a king that have been assumed by some to be a 4th-Dynasty pyramid builder, but which are rather more likely to represent Amenemhat II of the 12th Dynasty (ca. 1900 b.c.).

The sculpture, now in the Louvre, Paris, was found in 1825 among the ruins of Tanis in the Nile Delta, where it was likely moved towards the end of its ritual life in Pharaonic times.

This sphinx, however, carries the names of at least two subsequent kings: Merenptah, of the 19th Dynasty (ca. 1210 b.c.), and a ruler of the 22nd Dynasty called Sheshonq I (ca. 930 b.c.).

Neither of these later kings meant any ill-will to the original king the sphinx was carved to represent; it was a way, if not of honouring that king, then of harnessing some of his divine power.

This suggests a deep belief in the power of the materiality of the sculpted image—a power restricted largely to the elite, and never intended for dissemination to (or debate by) a wider ‘public’.

Today our attitude to sculptured human images is usually rather more detached. Yet not all statues stand passively in public spaces, blending into the urban backdrop—they can still be powerful agents, flashpoints of feeling, living images. With our digital saturation of the human image in two-dimensions, perhaps we have forgotten the power of the three-dimensional.

Source: Campbell Price, Nile magazine

DR. CAMPBELL PRICE is curator of Egypt and Sudan at Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, and Vice- Chair of the Egypt Exploration Society.