As part of an extensive research program undertaken in coordination with the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities and the University of Liège, an international team – including scientists from the CNRS, Sorbonne University, and the Grenoble Alpes University – has revealed the artistic licenses exercised in two ancient Egyptian funerary paintings (dated to around 1400 and 1200 BC, respectively), as evidenced by newly discovered details invisible to the naked eye. Their findings are published in PLOS ONE.

In the language of ancient Egypt, the word “art” is not known. Their civilization is often perceived as extremely formal in its creative expression, and the works produced by their burial chapel painters are no exception.

However, an international and multidisciplinary team led by CNRS researchers Philippe Martinez and Philippe Walter has brought to light pictorial techniques and practices whose faint traces had allowed them to evade detection for a long time.

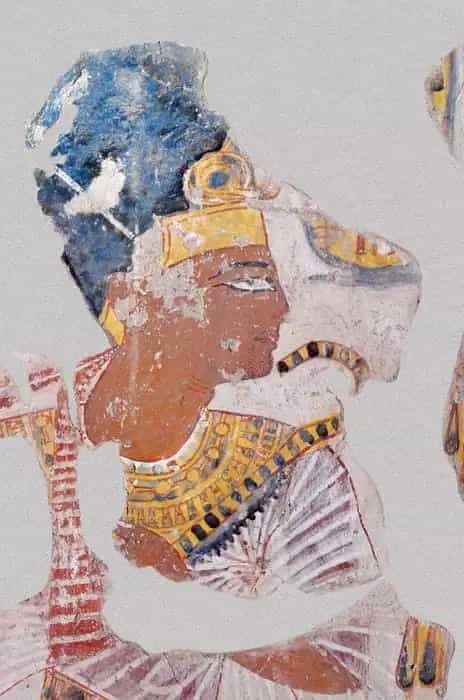

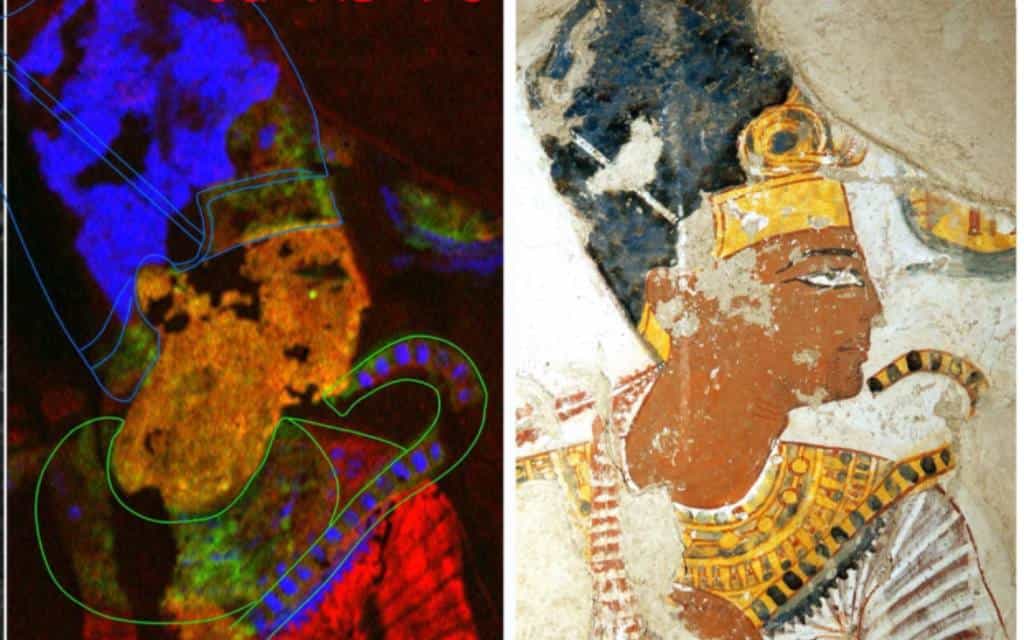

Studying the portrait of Ramses II in the tomb of Nakhtamun and the paintings in the tomb of Menna – among hundreds of other tombs of nobles in Luxor – they found evidence of retouching done to the paintings during their production.

For example, the headdress, necklace, and scepter on the image of Ramesses II have been substantially retouched, although this is invisible to the naked eye.

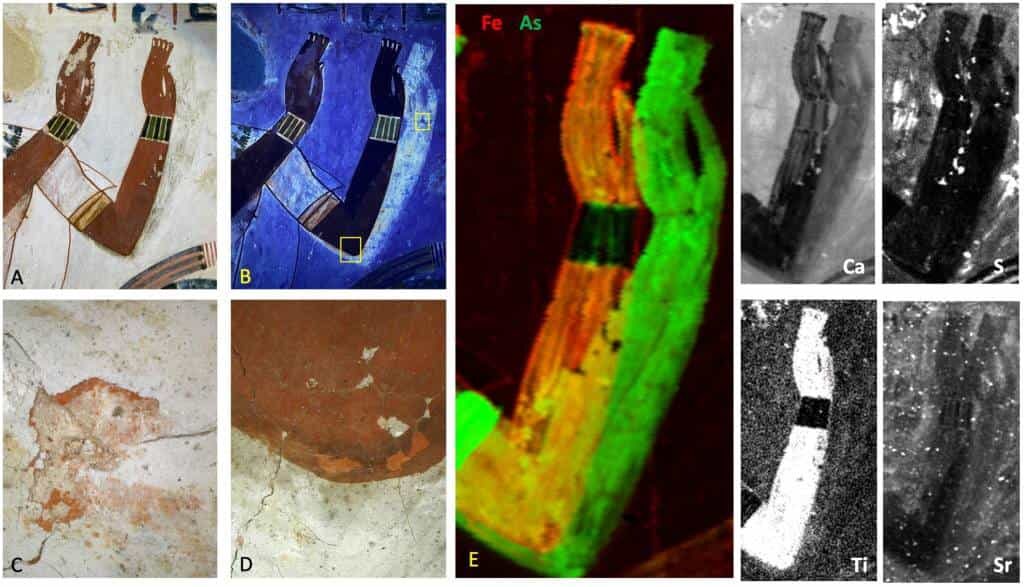

And in a worship scene depicted in Menna’s tomb, the position and color of an arm were changed, resulting in subtle changes whose purpose remains uncertain.

In this way, these painters or “draftsman-writers” – at the request of the individuals who commissioned their works, or at the initiative of the artists themselves as their own vision of them changed – could add their personal touches to the conventional motifs.

To make their discovery, the scientists relied on novel portable tools that enabled non-destructive in situ chemical analysis and imaging. Over time and due to physicochemical changes, the colors of these paints have lost their original appearance.

But the scientists’ chemical analyses, along with their 3D digital reconstructions of the works using photogrammetry and macro photography, should help restore the original hues and change our perception of these masterpieces, which have been too often considered static artifacts.

The team’s research shows that Pharaonic art and the conditions for its production were indeed more dynamic and complex than previously thought. The scientists’ next mission will be to analyze other paintings for new clues to the craftsmanship and intellectual identities of ancient Egyptian painters or “draftsman-writers.”