Although having children was the primary duty of Egyptian women, and offspring were a source of family happiness, some surviving medical papyri contain recipes and methods to prevent conception, which are undoubtedly extravagant and picturesque in today’s eyes. .

“Prevent a woman from being pregnant: crocodile excrement, impregnate a vegetable tampon with it and place it in the mouth of her vagina.”

As disgusting as the very idea of using a contraceptive method of such characteristics is today, we must conclude that this formula, which appears repeatedly in various ancient Egyptian medical texts such as the Ramesseum Papyri, preserved in the British Museum, it was one of the most used in ancient Egypt to prevent unwanted pregnancies.

The joy of having children …. But how to avoid them

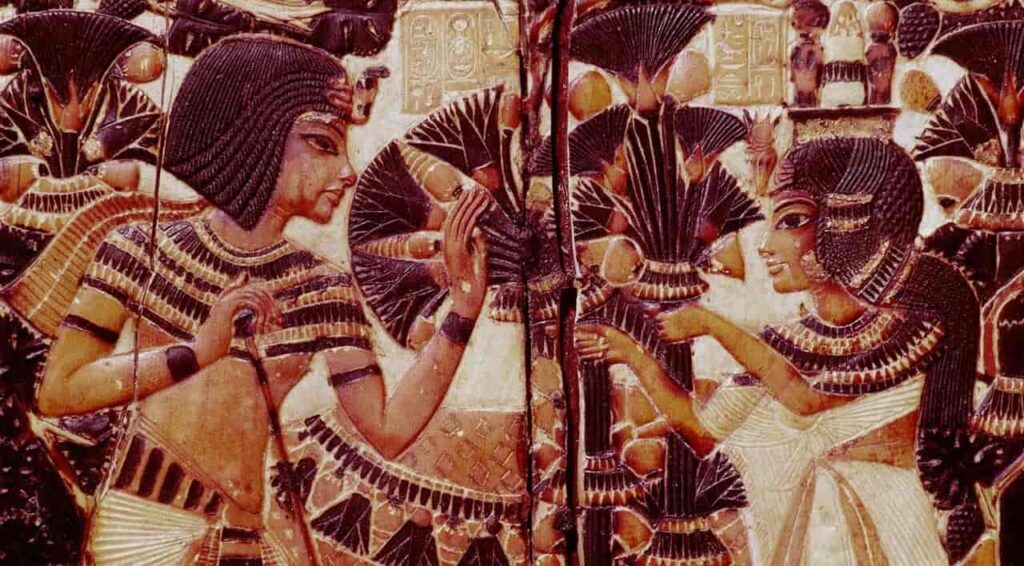

In Egypt, as in all ancient cultures, having children was considered a blessing. In fact, it was the primary role of women in marriage and a way of ensuring family continuity, preserving property, and ensuring a secure situation in old age.

The children also had to take care of celebrating the funeral worship of their parents after their death in order to guarantee eternal life.

Some Egyptian wisdom texts already said it, such as the Instruction of Any:

“Take a woman while you are young, so that she may have a child for you, when you are young. Teach your children to be adults. Happy is the man, whose people are numerous, he is respected in proportion to his children.”

For their part, Instruction of Hardjedef advised the following: “If you are well off, found a home; take for yourself a woman as mistress of the house, and a male child will be brought to you into the world.”

Even in Greco-Roman times the same premises were followed. For example, according to the Instruction of Ankhsheshonq a man should do the following: “Take a woman when you are 20 years old, so that you can have a child while you are still young.”

But sometimes, even in a society like Egypt, where birth was highly valued, there were times when conception was not desired, and various systems were devised to avoid it.

Although, some formulas vary, that most of the times it was vaginally, which suggests that ancient Egyptian doctors were aware of the way in which conception occurred and they knew that the best way to avoid it was through the female reproductive organ.

Another characteristic of all these methods is that they were always aimed at women. Contraceptive methods for men have not yet been found.

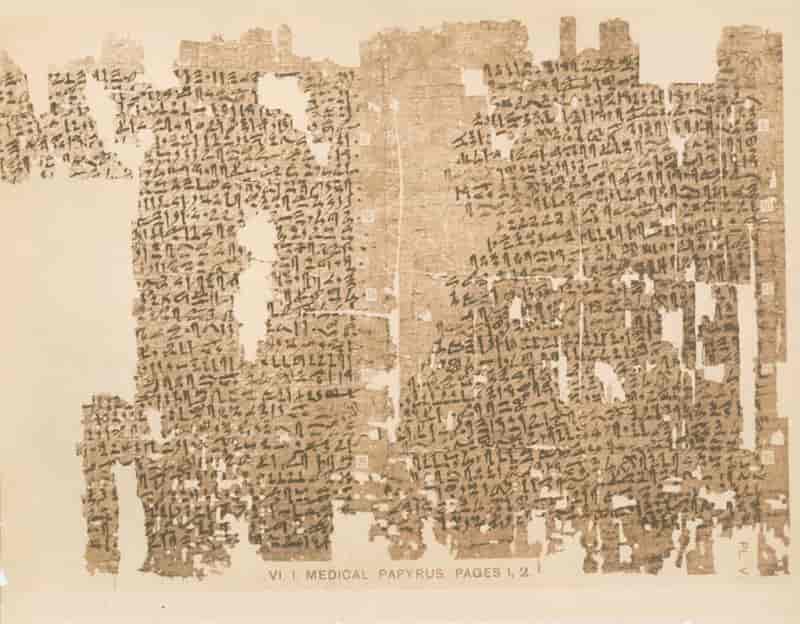

These methods were compiled into a series of surviving medical papyri (the most famous of which are the Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus, the Ramesseum papyri, the Brugsch Papyrus 3038, and the Ebers Papyrus).

All of them, in addition to contraceptive methods, also deal with the different gynecological problems that could affect women during pregnancy and childbirth, and propose methods against infertility, ways of knowing if a woman is pregnant or not, and even the way to find out the sex of the child.

Medical papyri

The oldest surviving medical papyrus is known as the Kahun (or Lahun) gynecological papyrus , dated to the reign of Amenemhat II, pharaoh of the 12th dynasty (1939-1760 BC).

It was discovered, along with other medical papyri, in 1899 by the British Egyptologist Sir William Flinders Petrie and is kept in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archeology in London.

The text is dedicated to female diseases and pregnancy, and among the contraceptive methods mentioned in this papyrus we already find the surprising (and apparently omnipresent) recipe made with crocodile feces: “Do not get pregnant, that […] crocodile excrement , mash with sourdough; soak […] “.

Another method mentioned in the text is this: “A jug- henuof honey; pour into your vagina. It can also be made with a natron solution.”

But why does it seem that the Egyptians were so bent on the efficacy of crocodile feces in preventing conception? It is also worth wondering about the difficulty (and especially the danger) of getting the main ingredient in this curious recipe.

Some researchers suggest that this material could block the passage of semen and thus prevent an unwanted pregnancy, or even that it could change the pH of the vagina and make it more alkaline (which would give it spermicidal properties).

The other recipe mentioned contains honey and natron (sodium carbonate used by the Egyptians in the mummification process), elements that could also be effective spermicides.

The so-called Papyri of the Ramesseum also contain gynecological texts. They date from the Thirteenth Dynasty (1759-1630 BC) and were found inside a funerary shaft on which centuries later the funerary temple of Ramses II, the Ramesseum, would be built on the western bank of Thebes.

Today these texts are preserved distributed between the British Museum and the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. As we have seen at the beginning of the article, they contain the famous contraceptive recipe based on crocodile excrement.

For its part, the Berlin Papyrus 3038 (also known as the Brugsch Papyrus) is part of a set of papyri also dating from the Middle Kingdom that were discovered by the Egyptologist Heinrich Brugsch at the beginning of the 20th century in the Saqqara necropolis, and that today are conserved in the Egyptian Museum of Berlin.

The text is quite deteriorated, but it details a contraceptive procedure that is still legible and that stands out for being an oral method, something very rare in ancient Egypt:

“You will administer a cereal fumigation – mimi(maybe wheat or sorghum) in contact with her vagina so that it will not be possible to receive his (semen?). You […] for her a remedy for the (?) Liberation (semen?): Oil river; 5 ro of celery (a vegetable with certain abortifacient properties); 5 ro of sweet beer. This will be cooked and eaten for four mornings.”

Other methods?

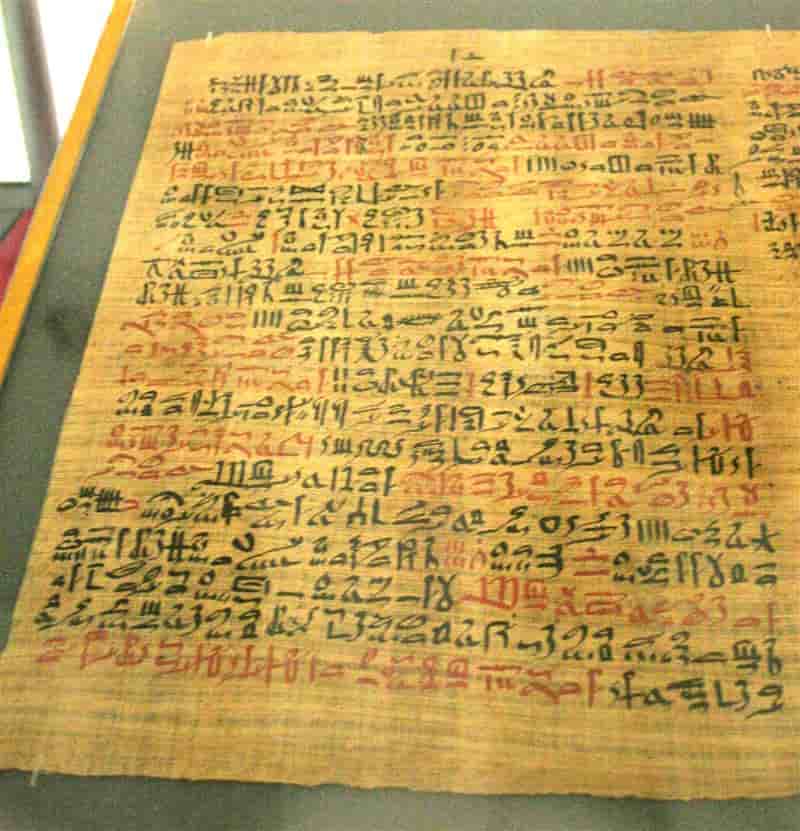

Finally there is the Ebers Papyrus, the longest medical text that has come down to us. It was discovered in a tomb at Assasif, in Luxor, in 1860 by the German Egyptologist Georg Ebers, and dates from the 18th dynasty (1539-1292 BC).

It is currently kept in the Leipzig University Library, in Germany. In the section that this papyrus dedicates to gynecology there is also a contraceptive prescription:

“To prevent a woman from getting pregnant for 1 year, 2 years or 3 years: qaa (perhaps the green fruit) of acacia (it seems that the acacia contains gum arabic, which has some spermicidal effect), planta- djaret (There is no consensus among specialists on which plant it is; perhaps colocynth or carob), dates (their sugars also have a spermicidal effect), finely ground in a jar – henu of honey. Soak a vegetable tampon there and place it in the vagina.”