INTRODUCTION

New Kingdom Chronology

The chronology of the period covers three dynasties, and includes two ways of governing. Eighteenth Dynasty was the heirs of the Seventeenth Dynasty, and go from 1550 to 1295. During the Eighteenth Dynasty, in which the most frequent names are Amenhotep or Tutmosis, the capital changes a lot, from Thebes, the great ceremonial city of festivals religious, to Memphis a century later and to Amarna around 1350 BC, a new city founded that will be the capital for about 30 years, when it moves again to Memphis.

From the Nineteenth Dynasty, the Egyptian throne will be occupied by military leaders who excel in the army.

Queen Hatshepsut:

Hatshepsut is an example of women who had real power in the New Kingdom period. The cause was the regency.

If her brothers / husbands died and their children were still small, the mother of the future king became a kind of protector of the kingdom, a regent, until the legitimate heir was old enough to reign by himself. In the case of Hatshepsut, she was queen regent while the future king Thutmose III (1479-1425 BC) grew.

Hatshepsut temple in Deir el Bahri

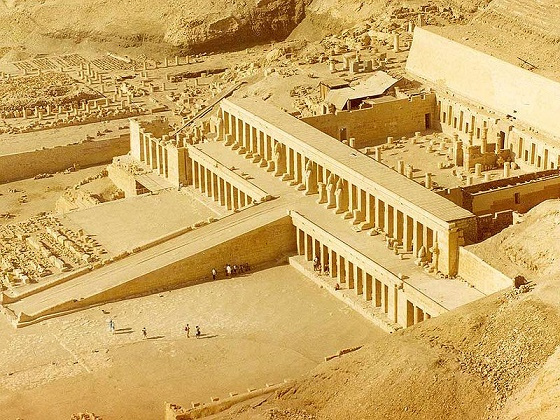

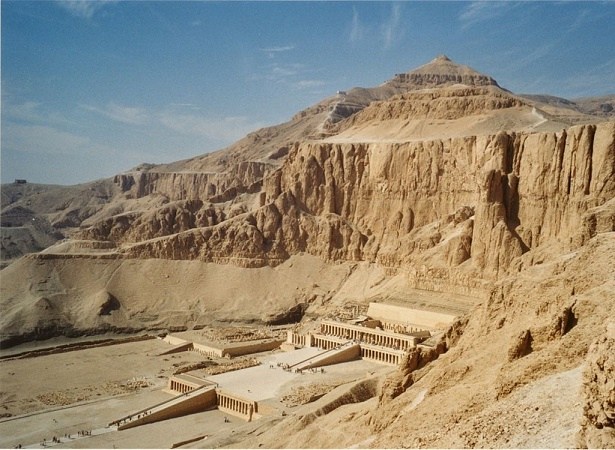

Hatshepsut temple in Deir el Bahri is one of the most famous mortuary temples, not only of the New Kingdom, but of the History of Egypt.

As reigns in the regency of Egypt, Hatshepsut inaugurated constructive projects that far surpassed those of their predecessors.

However, what is undoubtedly the most lasting monument that has come to us from the times of Hatshepsut is its mortuary temple complex of Deir El Bahari.

This temple is built with limestone and designed with a series of terraces that are arranged with their backs to a cliff. In addition, it must be said that the temple of Hatshepsut, technically called “the Holy of Holies” is the best source that we have to know her reign.

Design and background of the temple

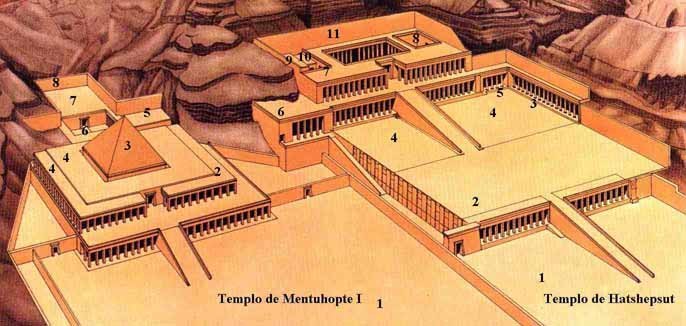

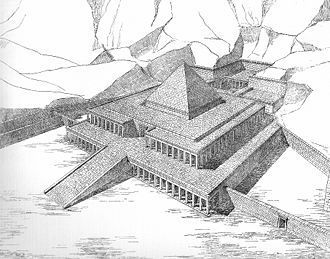

The design of the building does not keep secrets for historians, since it follows an architectural form known since the First Intermediate Period, and inspired above all by the temple that had to the side for centuries, the temple of Mentuhotep II (2061–2010 BC) , of the Eleventh Dynasty.

Reconstruction of what would have been the temple of Mentuhotep II, built centuries before Hatshepsut

Despite the great splendor of the temple, we know that Hatshepsut borrowed from her royal predecessors most of the architectural forms developed in her mortuary temple: for example, the colossal Osirian statues arranged in front of the square pillars of her colonnades are very similar to the statues of Senusret I or the Osirian Colossi of Thutmose I at the Karnak temple.

Scenes and inscriptions:

The finished temple included scenes and inscriptions that carefully characterized various aspects of Hatshepsut’s life and government.

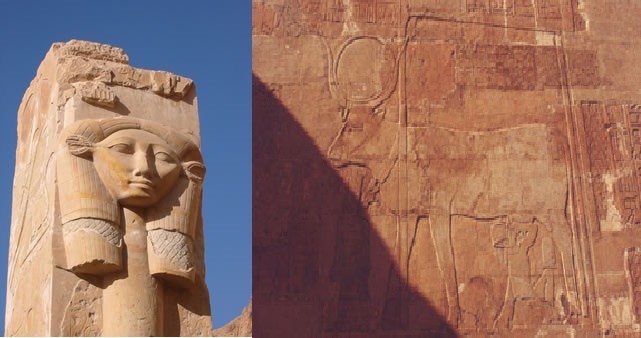

At the southern end of the middle terrace was built a chapel for the goddess of the western cemetery, Hathor, in front of which there was a courtyard with columns whose capitals were shaped like emblems of the cow-faced goddess. Even scenes are represented at the entrance of the chapel itself in which the queen is seen feeding the sacred cow.

On the upper terrace there is a central entrance to a courtyard with peristyle, that is, a courtyard surrounded by columns, behind which is the main sanctuary of the temple, while on the south side there are scenes from the Opet festival.

On this terrace there are also chapels for Hatshepsut herself and her father, Thutmose I. A proof of this is that in this part there is an inscription accompanied by a scene in which King Thutmose I proclaims the future reign of his daughter Hatshepsut.

Registration of private areas:

Another very defining feature of the reign of Hatshepsut can be known from a series of inscriptions of the private areas of the temple, designed to communicate with those few privileged who at that time, not only could read, but could have access to these areas private of the temple. These inscriptions refer to the unusual nature of Hatshepsut’s reign.

In them it is warned twice by her officials: “who honors her will live, who says evil things and blasphemes against her majesty will die» From the historical point of view, what this tells us is that Hatshepsut was very generous with those who supported her, and very ruthless with those who irritated or betrayed her.

In addition, it seems that Hatshepsut could have formed a symbiotic relationship with her nobles, so that the nobles were as indispensable to the queen as the queen to the nobles.