In the late 19th century, an extraordinary discovery emerged in Upper Egypt: the remnants of a burial site dating back more than five millennia, well before the rise of the Pharaonic dynasties. This ancient tomb, referred to as Tomb 100, was linked to an unidentified local ruler.

Although looted in antiquity, its discovery still captivated researchers due to the remarkable wall paintings found inside, which hinted at motifs and symbols that would later become prominent in Egyptian artistic tradition.

The tomb dates back to a distant era in Egyptian prehistory, known as the Gerzean or Naqada II period (approximately 3500–3200 BC). It is associated with the city of Nekhen, also known as Hierakonpolis, a major center in Upper Egypt.

This burial site was unearthed by archaeologists Frederick William Green and James Edward Quibell during their 1898–1899 excavation campaign at the ancient settlement. Despite hopes of finding an intact burial, the tomb had clearly been raided long ago.

Instead of the original burial treasures, the excavators discovered fragments of crushed bones, scattered pottery shards, and some flint tools. Yet, on the western wall of the tomb lay an unexpected treasure: a mural depicting scenes that seemed to foreshadow artistic themes and symbolism which would later flourish in Egyptian civilization.

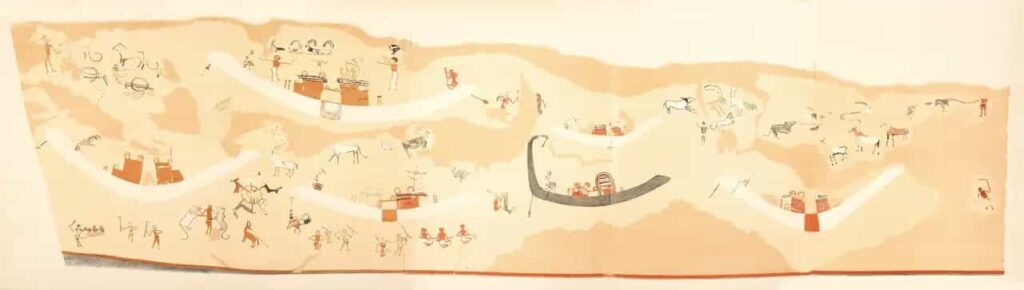

The wall paintings found within Tomb 100 at Hierakonpolis, though stylistically distinct from the art of later Egyptian periods, contain unmistakable motifs that would endure throughout ancient Egyptian history.

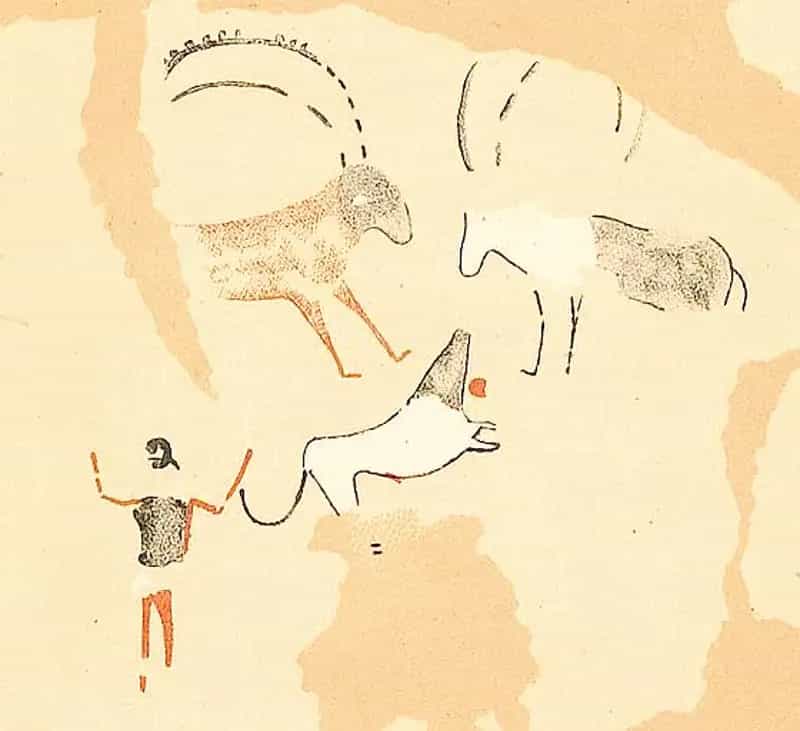

One such motif depicts a figure wielding a mace to strike down a group of captives, an image recognized by scholars as an early representation of the pharaoh triumphing over his foes—a recurring theme in Egyptian iconography.

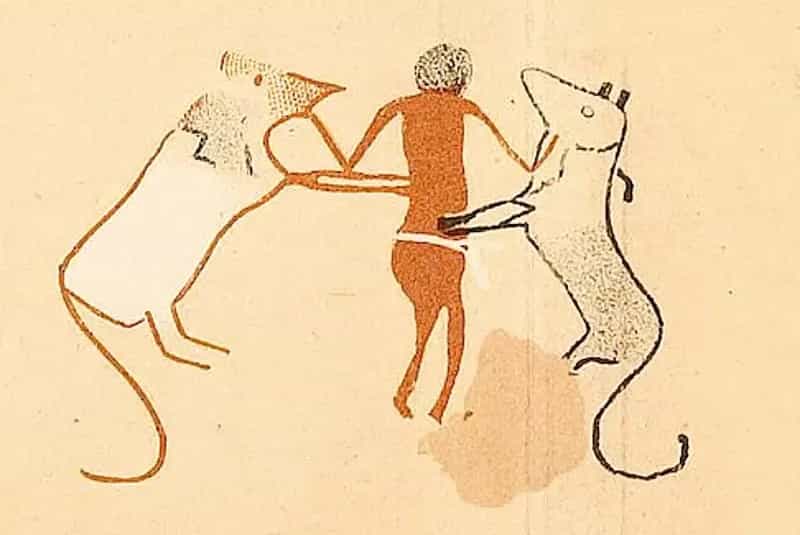

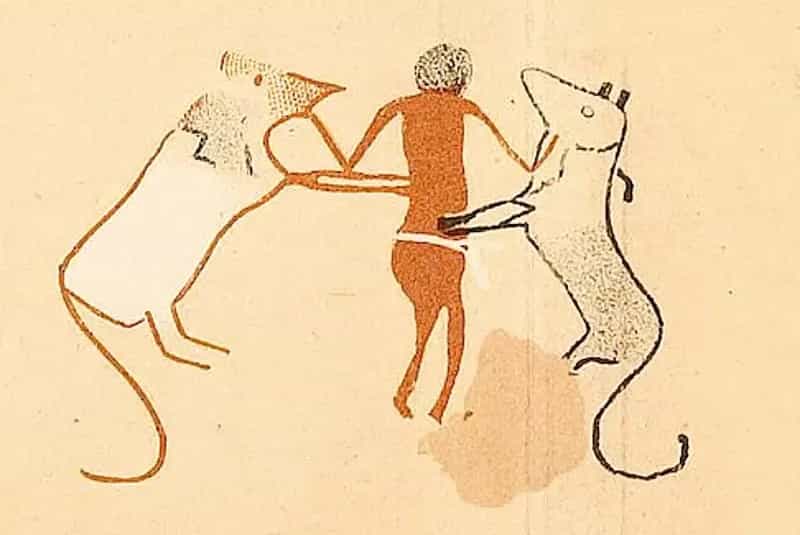

Another intriguing figure in the mural is shown grasping two lions, suggesting the ruler’s dominion over chaos, symbolized by the two powerful beasts representing opposing cosmic forces. Additionally, a separate character is depicted standing aboard a boat under a canopy, holding a staff and a scourge—emblems of royal power.

This scene may serve as a precursor to later depictions of the Heb Sed festival, where the pharaoh was believed to rejuvenate his vitality to continue ruling with renewed strength.

The mural’s depiction of six large boats, one carrying the figure of the ruler, adds another layer of significance. These vessels may not only signify power and authority but also evoke the passage of time and the cyclical nature of life.

Alongside these boats, various animals and human figures populate the scene, with the ruler depicted capturing the animals—an illustration of his ability to tame the wild forces of nature.

Experts generally concur that the fresco in Tomb 100, which spans 3 by 6 meters, symbolizes the struggle to impose order over chaos, a central theme in Pharaonic Egypt’s ideology.

The imagery reflects an early effort to establish royal authority during the predynastic era, a time when the transition to a settled way of life was still fresh, and society sought a leader capable of defending it against a perilous and unpredictable world.

Source: Carme Mayans, National Geographic