Egyptian Hieroglyphs first appeared in writing around 3300 BC and continued to evolve as a living language until the fourteenth century AD.

Over the span of more than four millennia, the language underwent significant changes. The gap between Middle Egyptian – the phase of the language in which the famous tale of Sinuhe was written – and Coptic could be as wide as that between Latin and Castilian.

Moreover, various dialects of the Egyptian language were spoken in different regions of ancient Egypt. For instance, it was common for a Delta inhabitant to struggle to understand someone from Elephantine (an island in the Nile).

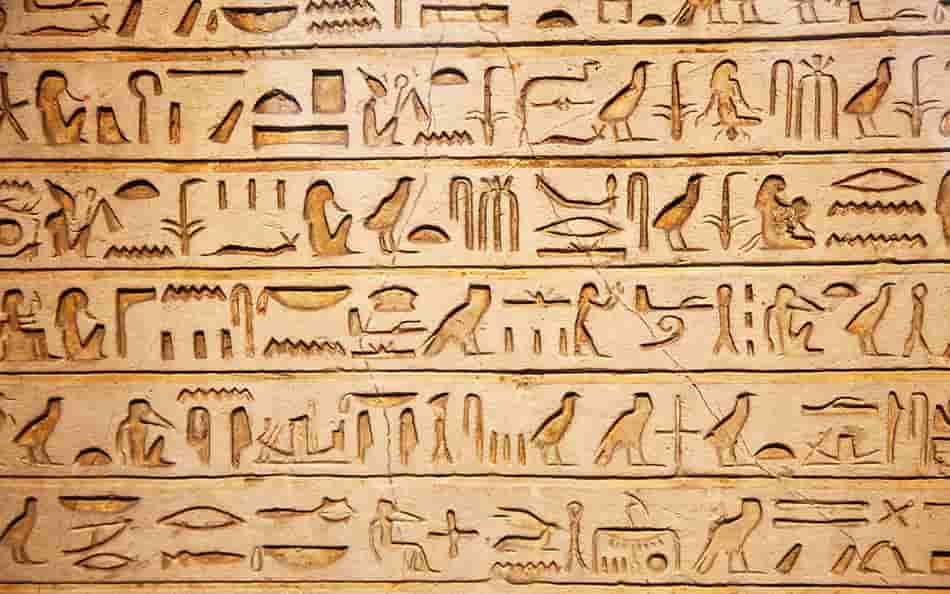

Given the remarkable transformation of the spoken language, hieroglyphic writing might give the impression of immutability, as if it were a sacred script that remained unchanged for centuries.

However, this impression is somewhat misleading. Throughout Egyptian history, there were not only different writing systems in addition to hieroglyphs, but these systems also evolved differently, even during the period of Greek rule.

Nevertheless, certain fundamental principles of hieroglyphic writing always remained valid.

Egyptian Hieroglyphs: Animals, Plants, and Objects

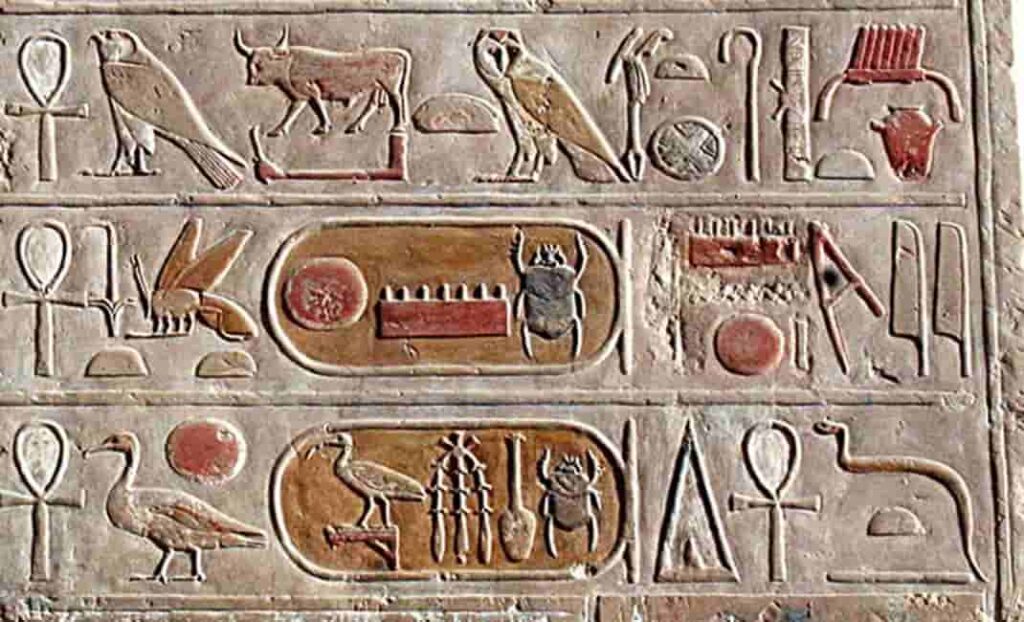

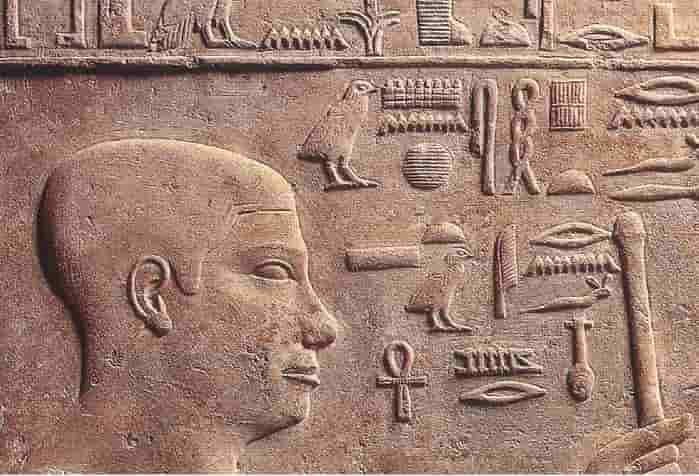

Hieroglyphs were always based on the representation of elements from the reality of ancient Egyptians, including human beings, animals, celestial objects, plants, various utensils, and all kinds of structures.

Initially, these signs were used as logograms, meaning their significance was the element they represented. For instance, the concept of “house” was conveyed through the schematic plan of a one-room house, and the word “face” was represented by a human head showing the face from the front. In such cases, a small vertical line was added behind or below the sign to indicate its use as a logogram.

Despite the considerable number of hieroglyphs created by the Egyptians – around 750 during the classical age of the Egyptian language – it was impossible to have one for every element of reality.

Additionally, abstract concepts that couldn’t be directly represented graphically needed a method for expressing new meanings using existing hieroglyphic signs.

One approach was to use the signs symbolically to represent concepts related to the element they originally depicted. For example, the sign representing the banners placed on the pylons (monumental entrance doors) of temples eventually came to signify the concept of god, as temples housed the statues of deities. Another example is the sign for the sun, which directly symbolized the sun king.

As this method proved inadequate, the Egyptians developed a phonetic writing system in which the signs represented the sounds or phonemes of words as they were spoken in the Egyptian language.

They utilized existing hieroglyphs, employing them in a manner similar to the letters in our alphabet. For instance, the sign representing an antelope, pronounced “jw,” was used to write words containing the sounds “jw,” even if they had no relation to the original meaning of “antelope.”

In some cases, hieroglyphs represented a single phoneme sound. For instance, the Egyptian word for “belly” was pronounced “khet,” so a sign representing the area of a cow’s belly with udders and a tail was used to represent a sound similar to “j.”

This phonetic writing method had the disadvantage of words being spelled the same and potentially causing confusion. To mitigate this risk, the Egyptians devised an ingenious procedure: they included a sign at the end of each word to indicate the class of objects to which it belonged, distinguishing it from other identically spelled words. These signs are known as determinatives.

Egyptian Hieroglyphs: Word Families

Thanks to the determinatives, it became possible to determine that the word in question corresponded, for example, to a specific type of plant.

Quadruped mammals were indicated by a determinative consisting of an animal skin and its tail. This way, a panther, Abyssinian, a jackal, or a mow cat could be designated.

A determinative in the form of a sealed papyrus scroll was used to identify abstract terms since papyrus was associated with conceptual thinking. Thus, the verb “to write” was formed with the sign of the scribe’s palette along with the determinative indicating it as an abstract concept.

On the other hand, the term “scribe” was designated by the same sign as the palette, but with the determinative of a seated man to indicate it as a profession.

Words could have more than one determinative, and during the New Kingdom, the number of determinatives used in each word multiplied.

Since hieroglyphs were written continuously without spaces between words, the determinatives also served another equally important function: assisting in locating the end of each term.

Egyptian Hieroglyphs: Different Combinations

It can be said, then, that hieroglyphic writing consisted of a combination of signs of various types: logographic, phonetic, and determinative.