Over the course of more than 30 different dynasties, the rulers of ancient Egypt became both conquerors of the world and conduits of the gods.

Ancient Egypt was a kingdom like no other. For 3,000 years a nation united as one, it expanded its horizons across the face of the Earth, erected true Wonders of the World and became one of the most powerful empires history has ever seen.

Yet for all those achievements, none would have been possible without the rulers at its head – the kings, the queens and the pharaohs.

Through the actions and decisions of over 170 men and women, Egypt became an epicenter for culture and philosophical thinking.

It became a place of polytheism, where a pantheon of gods lived in (relative) harmony and informed every facet of daily life.

But who were these figureheads and what was their true role in everyday Egyptian society? How did a king or queen rule a kingdom that stretched from the Nile to the Euphrates?

These questions have fascinated historians for centuries, and only now are we beginning to understand the responsibilities of a monarch in an age of deeply religious devotion and magical superstition.

Pharaoh of Egypt

The role of a pharaoh in Ancient Egypt is a complicated one, full of responsibilities and expectations, but it can be broadly defined by two distinct titles: ‘The Lord of Two Lands’ and ‘High Priest of Every Temple’.

Pharaohs were considered both divine figureheads and mortal rulers and as such were involved in everything from godly rituals to dispensing justice.

As king, the pharaoh was also the conduit of ma’at (truth, justice, prosperity and cosmic harmony – the key tenets of Ancient Egyptian society), so his sovereignty embodied both temple and state.

While pharaohs were often worshiped with the same religious fervor reserved for the gods themselves (such devotion was common in both life and in death – for instance, Ptolemy II, the second ruler of the Greek Ptolemaic Dynasty, had himself and his queen deified within two decades of their rule and welcomed the cults that formed around them), a pharaoh was still seen more as a divine conduit.

They were viewed not as the equal of creationary gods such as Amun-Ra, but as a manifestation of their divinity.

Pharaoh of Egypt: Death

In death, a pharaoh was just as influential as they were in life – the Egyptians viewed death not as the end of all things, but the immortalisation of the great and the just.

Cults would worship a pharaoh long after their death, while their name and deeds would live on in the constellations named after them and the monumental tombs erected to protect their wealth and prestige. However, the importance of an individual pharaoh was often relative.

Cults were sometimes disbanded so as to avoid undermining the sanctity of the current regime, while countless tombs and cenotaphs were stripped of their stone and precious limestone in order to facilitate the monumental building of later rulers.

As a mortal man, the pharaoh was the most important individual on Earth; surrounded by servants and dignitaries, they would operate from opulent palaces and coordinate religious doctrine with the help of the most prevalent church at the time.

Egyptian rulers often favored a particular god and through these deities certain churches rose to significant power, much in the same way Catholic and Protestant churches benefited or suffered from a given religious skew in Medieval Europe.

For instance, the god Amun became the patron god of the Theban kings for centuries, and his church became so powerful it caused one pharaoh (Akhenaten) to effectively outlaw it and establish another in its place.

A pharaoh would also coordinate the defense of the kingdom’s borders while leading every military campaign personally. What could be more frightening to a rebellious state or neighboring nation than a resplendent tool of the gods arriving to cast them aside?

They would oversee irrigation and the inundation of the Nile River, ensuring the fertile land along this body of water was fresh for agriculture.

The king would even commission the building of new temples and the renovation of existing monuments, with some rulers even destroying the work of their predecessors.

Ancient Egypt was a kingdom that embodied the personality of its ruler at that time.

For instance, Amenhotep III wanted to usher in a new golden age during the 18th Dynasty and spent a great deal of his reign beautifying the land.

Statues and temples were built, while an influx of wealth from military successes across the border had enabled him to adorn his palace and the capital of Thebes with gold and expensive cloth.

The daily life of a pharaoh would differ slightly between the dynasties, but overall his (or her) duties would remain the same. pharaohs of Egypt would often waken in a specially designed sleeping chamber.

The Ancient Egyptians were a people deeply in touch with their faith, a spectrum of dogma, science, magic and superstition. Just because a pharaoh was the divine manifestation of godly will on Earth didn’t mean he was free from worry or concern.

The Egyptians believed the dream world was a place where gods, men and demons walked the same path, so a pharaoh’s sacrosanct sleeping quarters would be adorned with spells and incantations, and perhaps statues or busts of Bes (the god of repelling evil) or Nekhbet (a goddess of protection) adorning the walls and columns.

The pharaoh would then move into the nearby Chamber of Cleansing, where he would stand behind a low stone wall to protect his royal modesty as a group of servants washed his body with warm and cold water.

After being dried with linen towels, the pharaoh would move into the Robing Room. Here, the Chief of Secrets of the House of the Morning (a man tasked with overseeing the monarch’s garments for every occasion) would coordinate the careful clothing of the king by another crew of servants.

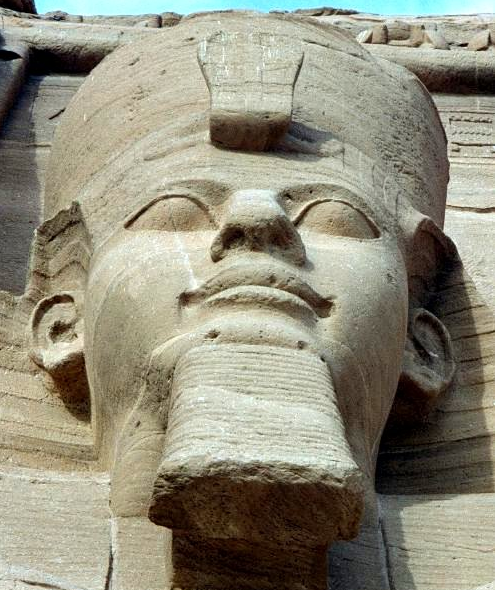

Since we only have stone pictorials or statues to present the image of the king, it’s easy to assume the Egyptian monarch wore a ceremonial headdress and carried an ankh and cane or flail wherever he went, but this is far from the reality.

Of course, for official ceremonies, such as the meeting of dignitaries of public addresses, the king would wear all the paraphernalia, but this was far from the case when it came to the laborious, day-to-day running of a kingdom.

The handlers of royal linen, the handlers of the royal crowns and headdresses, and even the director of royal loincloths would all gather around the king and dress him for the day to come.

Instead of the opulent gowns and sashes of formal wear, the king would have been dressed in a similar fashion to his courtiers. A simple linen tunic, sandals and a sash around the waist.

He wouldn’t have worn the heavy ceremonial crowns commonly seen on statues; instead he would have worn a simple diadem most likely made of silver and gold with a uraeus (a coiling cobra) at the front.

From there, the pharaoh would proceed to the temple adjoining the palace. He would pray to the gods and pay tribute alone before moving to the throne room to conduct the first meetings of the day.

The king would meet with his advisors and dignitaries from across the land every day, receiving reports from across the kingdom and ordering his officials to oversee certain aspects that require further attention.

Of course, while any citizen could petition for an audience with the king, not everyone made it to the throne room. Even those who did may well have only met with the vizier instead.

The pharaoh would pass laws into effect, but it seems most likely that many of these were ratified by his closest advisors so as not to drown the king in administrative duties. The pharaoh was the arbiter of his people and as such was always on the move.

Simply sitting in state in the nation’s capital would have been disastrous, so a successful pharaoh would visit every corner of his kingdom, inspecting the building of temples and overseeing the construction of new fortifications to protect the borders of his kingdom.

The visiting of temples was a vital part of a pharaoh’s roving duties – known more commonly as ‘doing the praises’, it was an awe-inspiring mark of respect to see the pharaoh and his court visit a temple and offer tribute to a local god.

Festivals were another important part of Egyptian culture, especially those that celebrated the sanctity of the pharaoh’s rule. The Opet festival, usually held at the Luxor Temple, would represent the renewal of the royal ka, or soul (the very life force of Egyptian society) and by association the power of the king himself.

The Sed festival, usually held in a king’s 30th year to celebrate their continued rule, was another huge occasion that would see the entire kingdom decked out in its finest decorations.

In short, these festivals were a testament to the love and reverence the Egyptian people had for their ruler. Yet, for all their influence and divine status, one man could not be in all places at all times.

As such, a pharaoh would often deputies his priests, tasking them with traveling to different corners of the kingdom to oversee new and existing temples.

He would often pass a great deal of responsibility onto members of the royal family, most notably the Great Royal Wife. A pharaoh of Egypt would likely take multiple wives, but only one would be his true queen, who would hold the most power outside of her husband.

While the lesser wives (who would range from foreign princesses to a pharaoh’s own sisters and daughters) would often remain at one of the king’s many palaces around the country, the Great Royal Wife would usually travel with the king as he conducted his duties.

Queens formed an important part of a pharaoh’s persona.

As the mother of princes, a queen could inspire cults and followings in her own right, and many of the most influential kings were immortalized in pictorials and statues with their favorite consort at their side.

When a pharaoh of Egypt was busy elsewhere – usually with overseeing the construction of a tomb or standing at the head of a foreign campaign – the running of the country was often left to his queen.

Some queens, such as Queen Tiye (the wife of Amenhotep III), were elevated to such a high position of power that they hosted foreign dignitaries and entertained kings with all the authority of their husband.

Of course, not all queens could boast such influence, but those most favored were still a formidable presence and influence in the royal court.

The hierarchy of the royal court, and Egyptian society as a whole, was often based upon an individual’s importance and contributions.

Directly under the pharaoh stood the queen, but in cases where the Great Royal Wife was not as elevated, a grand vizier would advise the king on matters of state.

Beneath the vizier and advisors were the priests and nobility of the royal court. These were the elite and were usually heads of the most powerful families of the period.

Beneath the nobility and the holy men were physicians, sages and engineers, followed by scribes, merchants and artists.

Finally, at the bottom of the hierarchical pyramid were the vast majority of the population – the everyday working people themselves.

From their inception with King Narmer and the First Dynasty, to their conclusion with the suicide of Cleopatra VII and Egypt’s absorption into the Roman Empire, the pharaohs were the epitome of royal power in the ancient world.

They commanded armies that conquered even the most bloodthirsty of enemies, orchestrated the construction of vast and impressive monuments that have survived to this day, and maintained over 30 dynasties that shaped the world around its majesty.

The pharaohs may now have been consigned to Ancient Egyptian history, but their mark upon that history will last forever.