Shiny and unalterable, gold was the metal most valued by the ancient Egyptians, who used it profusely in the trousseau and decoration of royal tombs.

In 1901, the great British archaeologist Flinders Petrie discovered in Abydos, in the tomb of King Djer, of the First Dynasty (about 3,000 BC), a mummified arm that someone had thrown into a corner.

The member, probably of a woman, was wrapped in linen bandages; when Petrie withdrew them, four splendid bracelets made up of gold, turquoise, lapis lazuli, and amethyst appeared before his sight.

The four bracelets, preserved in the Cairo museum in all their original brilliance, are one of the oldest testimonies of the presence of gold jewellery in ancient Egypt.

Certainly, in several predynastic tombs small samples of gold have been found, but it was in the Archaic period (the period in which the capital of Egypt was in Tinis, in Upper Egypt, until the Second Dynasty) that the Egyptian goldsmiths reached a great expertise.

This high level remained in the following periods, as shown by the findings in the pyramid of Pharaoh Sekhemkhet, Dynasty III and in the tomb of Queen Hetepheres, of the Fourth Dynasty.

At that time, the ancient Egyptians obtained their gold in relatively close deposits, in particular in the wadis (dry river courses) of the eastern desert of Upper Egypt, in the south of the country.

It was not until the Middle Kingdom, at the end of the third millennium BC, when gold began to be imported massively from Nubia, in present-day Sudan.

The consequent abundance of gold fueled the taste for jewelery at court, while the artistic influence of the Near East and the Aegean inspired new forms and techniques of goldsmithing.

It could be said that it was in the Middle Kingdom that Egyptian goldsmithing reached its zenith.

The treasures exhumed by Petrie and Jacques de Morgan at El Lahun and Dashur, respectively, in various tombs of queens and princesses of the 12th Dynasty, reflect the perfection that the art of jewelry-making achieved.

In the New Kingdom, the famous treasure of Tutankhamun, pharaoh of the eighteenth dynasty, in the mid-fourteenth century BC, it does present original aspects in thematic and forms.

During the Twenty-first Dynasty, three hundred years later, the techniques and motifs reached perfection; An example of this are the superb vases found in the tomb of Psusennes I.

There are numerous testimonies of the passion Egyptians felt for gold.

One of the most spectacular is the Middle Kingdom treasure that the French archaeologist Fernand Bisson de La Roque found in 1936 among the remains of a temple erected in honor of King Sesostris I, second pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty, which appeared under the rubble of a Greco-Roman temple in the town of El-Tod.

First discoveries

Less than a meter deep, Bisson de La Rocque came across a cache containing some bronze statuettes from the 12th Dynasty, and very close by he found four heavy bronze chests.

Both on its lids and on its closing knobs, Bisson could read the coronation name of Amenemhat II, son and successor of Senusret I.

The chests contained a veritable treasure of gold, silver and lapis lazuli. Two of them kept, between jewels and silver ingots, ten gold ingots, numbered in hieratic from one to ten, each weighing 6,505 kilograms.

Tod’s treasure, which today we can see in the museums of Cairo and the Louvre, could be interpreted at first glance as a sample of the filial love of Amenemhat II towards his father Senusret I, in the form of an invaluable gift. However, the use of gold had deeper meanings in ancient Egypt.

In earlier times, royal funeral offerings of exceptional wealth had been made to the deceased, which were not limited to providing the deceased with food and daily supplies necessary for life in the Hereafter.

For example, the French archaeologist Jean-Philippe Lauer found in the underground galleries of the pyramid of King Djoser, of Dynasty III, about 40,000 elaborately chiseled stone vases .

Such a number of glasses makes it impossible to consider them as simple containers of food or drink to serve the deceased.

Made by the best artisans of the time, stone vases were at that time the greatest exponent of high social and economic status, and conveyed the idea that the more vases there were, the greater the power of their owner.

This same significance passed, redoubled, from worked stone to gold when it became, in the Middle Kingdom, the metal in fashion at court.

The metal of the gods

Gold topped the hierarchy of precious metals, ahead of silver and, of course, copper. This is partly explained by its physical characteristics.

Obsessed with the permanent, so that it never dies, the Egyptians could not stop giving priority to the unalterable metal par excellence.

But there was also a deeper religious explanation. The brilliance of gold evoked the radiance of the god Ra in all his majesty, the sun at its zenith.

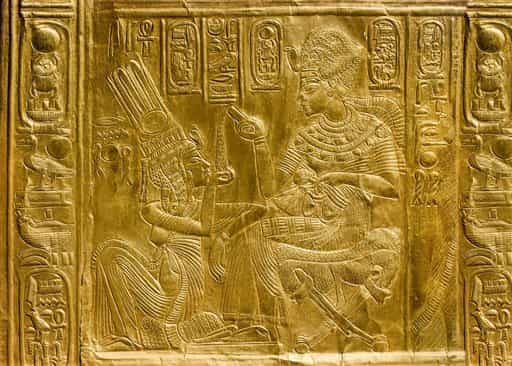

In fact, gold was believed to be the flesh of the gods, while their bones were silver and their hair were lapis lazuli.

As, in addition, the ancient Egyptians considered the pharaoh the son of the sun and identified him with Ra, they used gold in abundance in the funerary equipment of their kings.

One of the formulas in the Book of the Dead, for example, states:

“Your hair is decorated with lapis lazuli; the upper part of your face is the radiance of Ra; your face is a sheet of gold and Horus has enhanced it with lapis lazuli [ …] Your neck is adorned with gold and lined with fine gold […]; your back is adorned with gold, it is lined with fine gold”.

According to this conception, gold possessed regenerative power and aided the deceased pharaoh in his rebirth as Osiris.

Hence, in the royal tombs of the Ramesside period, burial chambers called “gold chamber” were created, where the regeneration of the deceased king was carried out.

Many of these chambers were painted yellow, a color associated with gold and which was also imitated by painters in their modest hypogea in the artisan village of Deir el-Medina.

The biggest reward

Given the intimate association between the pharaoh and gold, the king was the only legitimate owner of the valuable metal, so that only he could grant it, as a divine gift, to certain characters and for exceptional events.

Thus arose a royal gift called “reward gold” or “value gold”, the most distinguished gift that the king granted to his subjects for extraordinary services, whether of a civil nature or acts of value on the battlefield.

This gift took the form of heavy necklaces made of gold discs, called shebyu. In the paintings of Ay’s tomb in Amarna we see how Pharaoh Akhenaten hands them over to Ay and his wife Tey from the “balcony of the apparitions” of his palace.

General Horemheb, in his tomb in Memphis, also exhibits these necklaces given by Tutankhamun.

Source:

National Geographic

The gold of the pharaohs. HW Müller and E. Thiem. Libsa, 2001.

Tutankhamun. The treasures of the tomb. Zahi Hawass. Akal, 2008.