On January 3, 1924, Howard Carter made a groundbreaking discovery in the Valley of the Kings. The British archaeologist, renowned for unearthing Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, returned to the site to continue the meticulous exploration of the young pharaoh’s burial chamber.

He and his team faced the monumental task of dismantling four golden funerary chapels that nearly filled the entire chamber. Each chapel, crafted from gilded wood, had to be carefully removed, one by one, to reveal what lay beneath.

A sarcophagus hidden among chapels

Carter had resumed work in early 1924 after a pause since April 6, 1923, and it was now time to penetrate deeper into the heart of the tomb. As the last chapel was opened, Carter’s anticipation reached a peak.

The final chapel was adorned with figures of the goddesses Isis and Nephthys, their wings outstretched as if guarding the precious secret within.

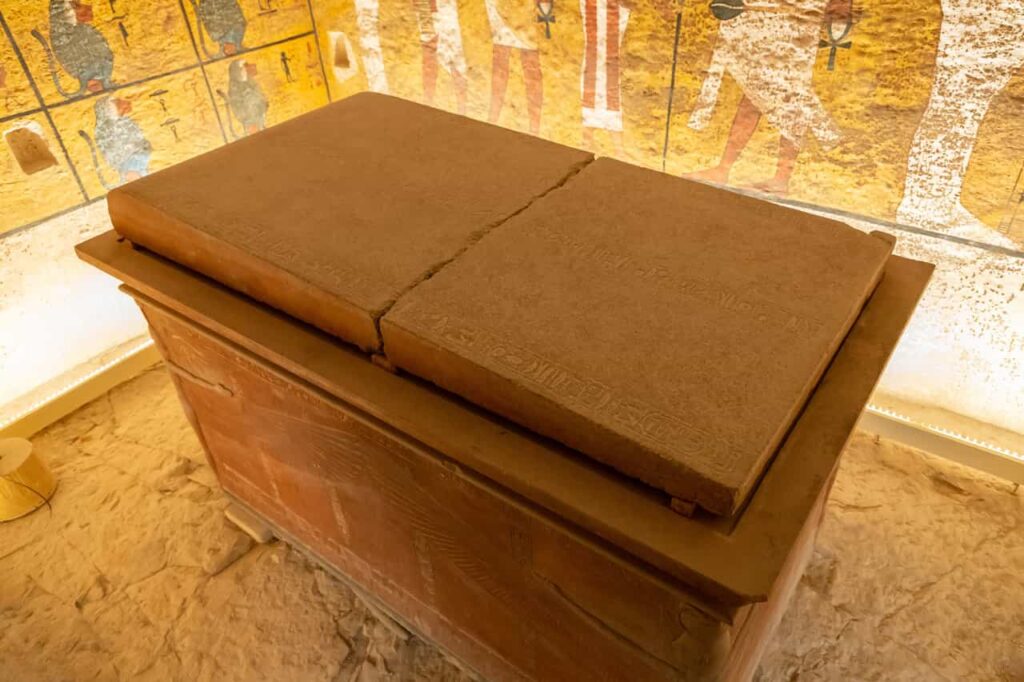

Upon opening the final barrier, Carter and his team uncovered a magnificent quartzite sarcophagus. Still sealed and perfectly preserved, the massive stone sarcophagus stood untouched, just as it had been left by the ancient embalmers. Its colossal lid remained firmly in place, shielding the treasures inside from the outside world.

However, the journey to this discovery was not straightforward. The outer chapel dominated the chamber, leaving little room to maneuver. Moreover, the narrow spaces were filled with various artifacts, including wooden staffs, ostrich feather fans, and alabaster containers, further complicating the excavation. These items had to be meticulously documented, packed, and removed to clear the way.

Only after Carter’s team had painstakingly emptied the burial chamber of its contents could they proceed with the dismantling of the chapels, a process that would take over a year to complete.

Hidden within this intricate setup, the quartzite sarcophagus and the treasures it protected provided yet another glimpse into the grandeur of Tutankhamun’s final resting place, a discovery that would echo through the annals of Egyptology.

Lifting the lid of the sarcophagus

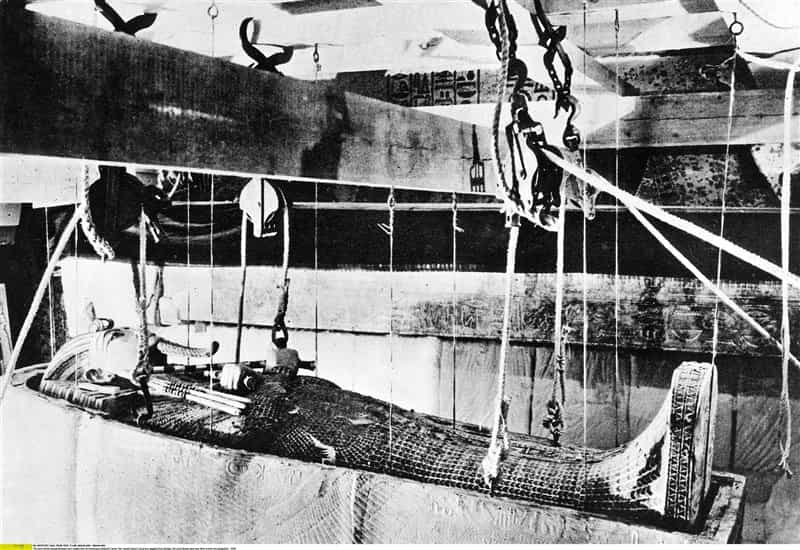

On October 13, 1925, Howard Carter and his team took a significant step forward in the exploration of Tutankhamun’s tomb by beginning to dismantle the shrines that encased the intricate quartzite sarcophagus.

With the heavy gilded shrines now being carefully removed, the team gained better access to the sarcophagus itself. But as they prepared to examine it more closely, Carter was met with an alarming discovery: a visible crack ran across the massive lid.

The crack posed a substantial risk because the lid, weighing roughly one ton, could potentially break apart during the lifting process, endangering the precious contents inside.

To address this challenge, the archaeologists devised a system of improvised pulleys to lift the lid with caution, ensuring that all ends were supported to prevent any accidents.

With the lid successfully raised, Carter anxiously looked inside and found an anthropoid coffin crafted from gilded wood. The coffin was shaped in the likeness of the young pharaoh, with a striking golden face, arms crossed over the chest, and the traditional royal symbols of the crook and flail in hand.

However, there was evidence that even the ancient embalmers had encountered difficulties during the original burial. The coffin had been slightly too large for the sarcophagus, and the workers had resorted to shaving down the base to make it fit. Small wood shavings left behind bore witness to their last-minute adjustments.

A solid gold coffin

Upon opening the first coffin, Carter and his team were astonished to find a second coffin nestled inside, even more exquisite than the first. This inner coffin, crafted from gilded wood and adorned with intricate inlays, left the archaeologists in awe.

Howard Carter himself described it as “the most splendid example of the ancient art of coffin-making ever seen.” He likened the process to peeling an onion, layer by layer, as they drew closer to the young king’s remains.

The excitement grew as they lifted the lid of the second coffin, revealing a third and final one. This last coffin was draped in linen shrouds and adorned with garlands of flowers, possibly left there by Queen Ankhesenamun, Tutankhamun’s grieving widow.

As Carter gently removed the floral remnants and folded the shroud away, he uncovered a truly astonishing sight: the third coffin was made entirely of solid gold. It was an “absolutely incredible mass of pure gold,” as Carter would later recall, shining brilliantly even after more than three thousand years.

The long-anticipated moment had arrived at last. With great care, the team lifted the heavy gold lid, revealing the mummy of Tutankhamun. The boy king’s face and shoulders were protected by a breathtaking funerary mask crafted from gold and lapis lazuli, its beauty and craftsmanship so stunning that it left all who saw it speechless.

The mummy of Tutankhamun

Carter took a moment to absorb the gravity of the discovery before proceeding with the next steps. Using a scalpel, he began to cut through the thirteen layers of linen that wrapped Tutankhamun’s body.

As he worked, Carter found numerous treasures hidden among the bandages, including two remarkable daggers—one with a blade of pure gold, and the other forged from meteoric iron, which made it exceptionally rare and valuable.

Additionally, a gold breastplate was placed around the pharaoh’s neck, and a collection of protective amulets emerged from within the wrappings, totaling an impressive 143 items.

Source: Carme Mayans, National Geographic