With Egypt re-united after the disruption of the First Intermediate Period, royal life resumed. Superficially, little had changed, and slender, beautiful queens continued to support their powerful husbands.

But a closer look shows that the role of the royal women had been diminished. Although we know the names of many of the Middle Kingdom queens (such as Senet), and in some cases we have the privilege of peeping into their jewellery chests, it was not until the end of the Twelfth Dynasty that royal women started once again to play an obviously important political role.

The Queens of the Deir el-Bahri Bay

The Eleventh Dynasty king Nebhepetra Mentuhotep II claimed to be the ‘Son of Hathor’. This may explain why he built his funerary complex in the shelter of a natural bay at Deir el-Bahri, Thebes, a site strongly associated with Hathor in her role as Goddess of the West.

Mentuhotep’s own temple-tomb took the form of a double-terraced base, which may have been topped by a small pyramid. His complex included separate tombs for two significant queens, Tem and Nefru.

Six additional royal women were provided with shaft graves and limestone chapels. As the entrances to their graves were covered by the king’s own building works, we can deduce that all six died relatively early in Mentuhotep’s reign.

The graves were allocated to the King’s Wives Henhenet, Sadeh and Ashayt; the unexplained ladies Kemsit and Kawit (probably also royal wives), and Muyet (or Mayt) who was approximately five years old when she died.

Speculation that all six women died together, killed by an unspecified epidemic or accident, is unfounded. Certainly Henhenet died of natural causes; her mummy shows that she died in childbirth.

Murder in the Harem

There is good circumstantial evidence to suggest that the first king of the Twelfth Dynasty, Amenemhat I, was murdered in a harem plot. The details of Amenemhat’s death are preserved in a letter that claims to have been written by the murdered king to his son.

It tells how the king was asleep in the palace when his guards attacked him and “the weapons that should have been used in my protection were turned against me.” We have no official record of this murder.

However the letter is supported by the fictional story of Sinuhe, which tells how the hero of the tale flees Egypt when he learns about the king’s death. Why would Sinuhe run away if the elderly Amenemhat had died of natural causes?

We know that Sinuhe was in the service of the royal harem: “I was … a servant of the royal harem assigned to the Princess Nefru, wife of King Senusret and daughter of King Amenemhat”, and can guess that he knew more about the death than he should have.

Princess Nefruptah

Amenemhat III was the last powerful king of the Twelfth Dynasty. His reign saw important building works, impressive irrigation and land reclamation schemes and a series of successful mining expeditions.

This obvious prosperity makes it difficult to understand how the Twelfth Dynasty could suddenly fail. Although various theories have been suggested, it may simply be that the royal family lacked an appropriate male heir.

Support for this theory comes from the burial chamber of Amenemhat’s own Hawara pyramid (above). Here an additional sarcophagus was included for the King’s Daughter Nefruptah. This lady must have been either Amenemhat’s own daughter or, less likely, his sister.

It is difficult to reconstruct events in the burial chamber, but it seems that Nefruptah, having died unexpectedly, was interred in Amenemhat’s tomb while the builders completed her own monument. She was then moved to her own pyramid, a structure that is today almost totally destroyed and disastrouslywaterlogged.

This pyramid was investigated by Labib Habachi (1936) and Naguib Farag (1950s). It yielded grave goods including an offering table, silver vessels, pots, strips of mummy bandage and a pink granite sarcophagus inscribed with Nefruptah’s name.

The obviously close relationship between Amenemhat III and his daughter, and Nefruptah’s use of a cartouche in her later inscriptions, suggests that she was being trained to succeed her father.

King Sobekneferu

With Nefruptah already dead, Amenemhat III was succeeded by his (probable) son Amenemhat IV. He in turn was succeeded by his half-sister and probable wife Sobekneferu (known as Nefersobek to early Egyptologists and Scemiophris to the Classical historians).

Sobekneferu consistently associated herself in her inscriptions with the powerful Amenemhat III rather than her less impressive brother.

She may even have been the first to deify Amenemhat III as a god of the Fayum; this would have made good political sense, as the daughter of a god would have been regarded as a highly suitable king.

There is nothing to suggest that Sobekneferu was a temporary regent ruling on behalf of an infant son. Indeed, a glazed cylinder seal, now in the British Museum (below), confirms her status by recording her name in a cartouche followed by her Horus name ‘The Female Hawk, beloved of Ra’ and her titles ‘Mistress of the South and North’.

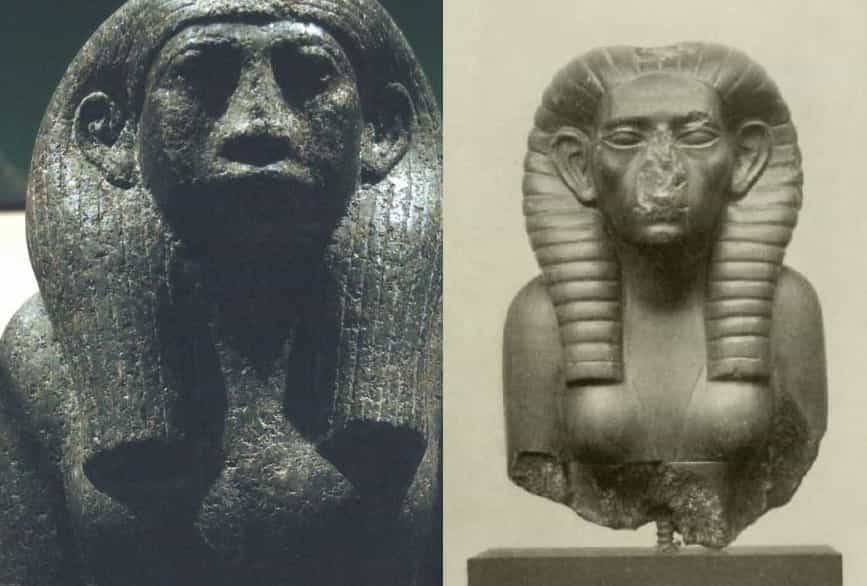

We have at least three headless statues of Sobekneferu which were found at Avaris but which probably originated in the Fayum region.

The most remarkable of these, now displayed in the Louvre Museum, Paris (top right), shows the queen’s female torso dressed in a conventional female dress, but with a male king’s kilt worn over the top, and a male king’s headcloth on her now vanished head. Sobekneferu is here struggling to conform to tradition.

A king of Egypt should look, dress and act like every other king: tall, muscular, kilted, bearded, capable of killing enemies, and male. No matter what the king looked like in real life, this is how he should appear before the gods and the people.

Indeed, the very act of portraying the king as an idealised being will help him (or her) become one. Without denying her femininity – she almost invariably uses feminine titles – Sobekneferu has decided to don the regalia that will transform her from a mortal queen to an almost-divine king.

Sobekneferu reigned for just less than four years. We would expect her have been buried beneath a king’s pyramid. However, she has no identified tomb.

Recovered architectural fragments suggest that her building activities were centred on the Fayum region, and this is presumably where she was buried. Her death saw the end of the Twelfth Dynasty.

Source:

Joyce Tyldesley. Joyce is a Senior Lecturer in Egyptology in the Faculty of Life Sciences at Manchester University.

Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt (Thames and Hudson).