Hippopotami held a complex place in ancient Egyptian society, where they were seen both with admiration and fear. Despite their association with certain positive attributes, these powerful animals were also regarded as highly dangerous.

The unpredictable nature of hippos, combined with their impressive strength, made them formidable adversaries. When threatened, they could become extremely aggressive, even outpacing a human over short distances.

Attacks on boats were not uncommon, with hippopotami capable of overturning vessels and injuring passengers. Although ancient Egyptians did experience attacks, evidence suggests some survived, as seen in an ancient medical text detailing treatments for hippo-inflicted wounds.

Primarily herbivores, hippopotami graze during nighttime, posing a significant threat to agriculture. Their substantial appetites could devastate fields overnight, leading to crop loss. An ancient papyrus records such an incident, stating, “the worm took half and the hippopotamus ate the rest,” highlighting the long-standing issue of hippos damaging farmland.

Today, hippos are extinct in Egypt, but their population began declining as early as ancient times. Habitat encroachment and hunting practices took a toll on their numbers, leading to a steady decline over centuries. The last sightings of wild hippos in Egypt occurred in the early 1800s.

Hunting hippopotami was a common practice in ancient Egypt for multiple purposes. Their meat, hide, and fat were valuable resources, while their large tusk-like canines, which could grow up to one-and-a-half feet, were particularly prized.

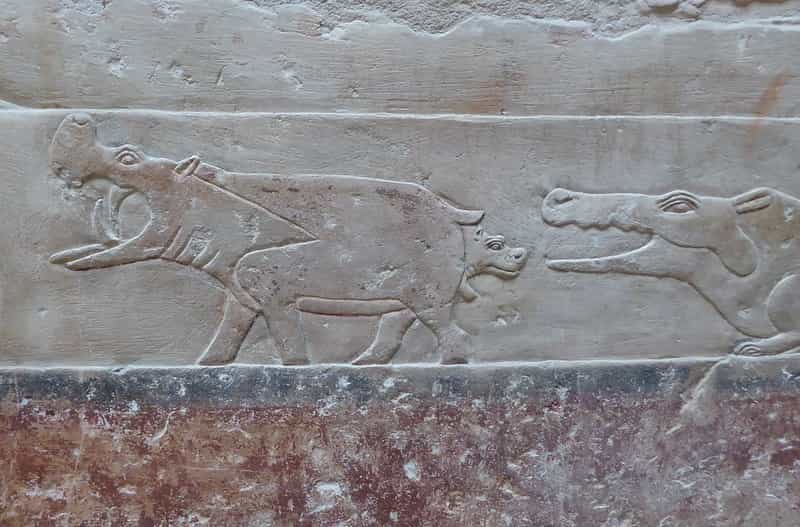

Depictions of hippo hunts date back to the Predynastic Period (circa 4400–3100 B.C.) and continued for over three millennia. These scenes typically illustrate a hunter poised on a small boat, holding a harpoon in an extended arm, ready to strike the formidable animal.

Ancient Egyptian harpoons used for hunting consisted of a wooden shaft tipped with metal or bone. When a hunter struck an animal, the tip would detach from the shaft but remain embedded in the flesh, allowing it to stay attached via a rope.

Illustrations frequently depict this rope hanging from the harpoon, with the hunter also holding a coil of ropes in the other hand. These ropes, already secured to the hippopotamus from previous hits, were designed to track the animal. Small floats were often attached to the ropes, helping hunters locate the hippo if it submerged and swam away.

In artistic portrayals of hippo hunts, the animal is typically depicted with its mouth wide open, a natural defensive posture for hippos. When threatened, they bare their teeth by opening their mouths, making them vulnerable targets for hunters aiming to strike at their most exposed spots.

In early societies, hunting a hippopotamus, an animal known for its ferocity, was a demonstration of bravery, strength, and dominance—qualities expected of a leader. By around 3000 B.C., images of Egyptian kings engaging in hippo hunts began to appear, reflecting the symbolic significance of these acts.

The hippopotamus, associated with chaos, was a representation of disorder that needed to be controlled. Thus, depictions of a king defeating a hippo symbolized his triumph over chaos and his role in sustaining world order, an essential duty of the Egyptian ruler.

It is believed that hippos were occasionally captured and kept alive for use in later ceremonial hunts. During such rituals, the king would ritually “hunt” and kill the hippopotamus, reaffirming his royal responsibilities and demonstrating his power as a conqueror.

Starting in the New Kingdom period (circa 1550–1070 B.C.), the hippopotamus became associated with the god Seth, who was later regarded as a symbol of evil. In Egyptian mythology, Seth was a rival of Horus, the deity representing the idealized king.

The myth of Horus and Seth recounts their struggle for the throne, which culminates in Horus defeating Seth and claiming rulership. Ritual reenactments of this myth were carved around 100 B.C. on the walls of the Edfu temple, where scenes depict Horus, often accompanied by the king, harpooning Seth, who takes the form of a hippopotamus.

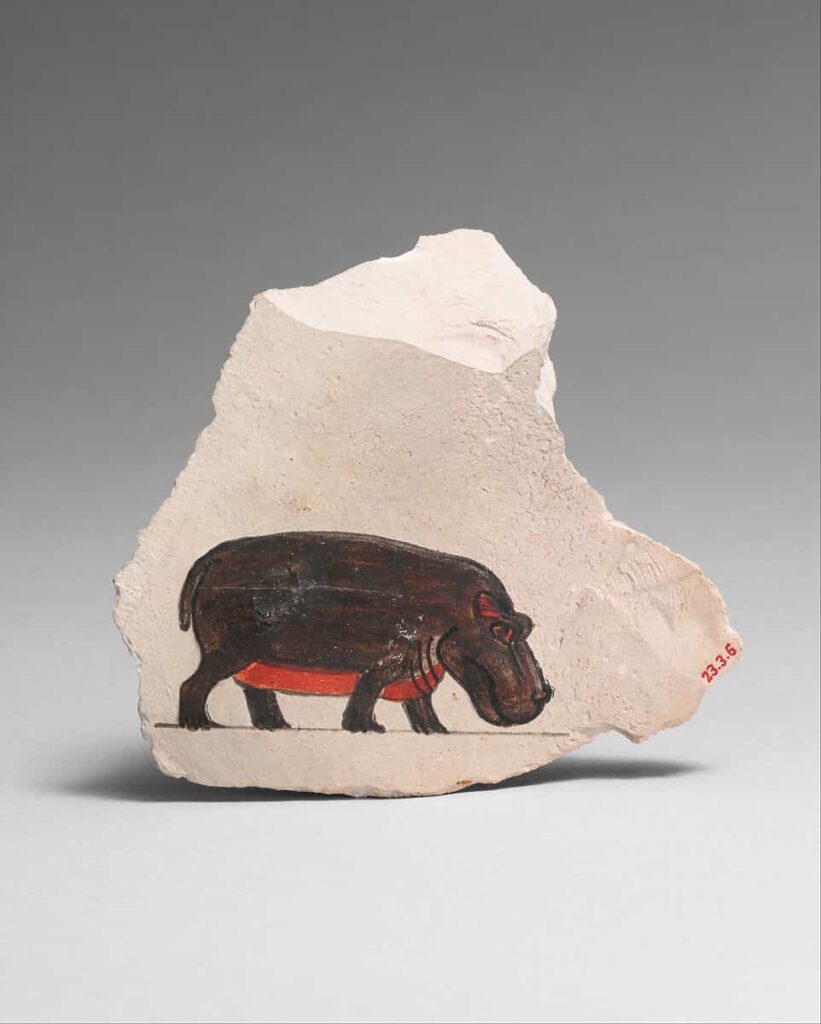

Despite this negative association, the ancient Egyptians also recognized the hippopotamus as a creature with positive attributes. Living in the Nile River, a vital source of life, hippos were linked to the concept of life itself. Their habit of submerging in water for several minutes before resurfacing to breathe symbolized regeneration and renewal.

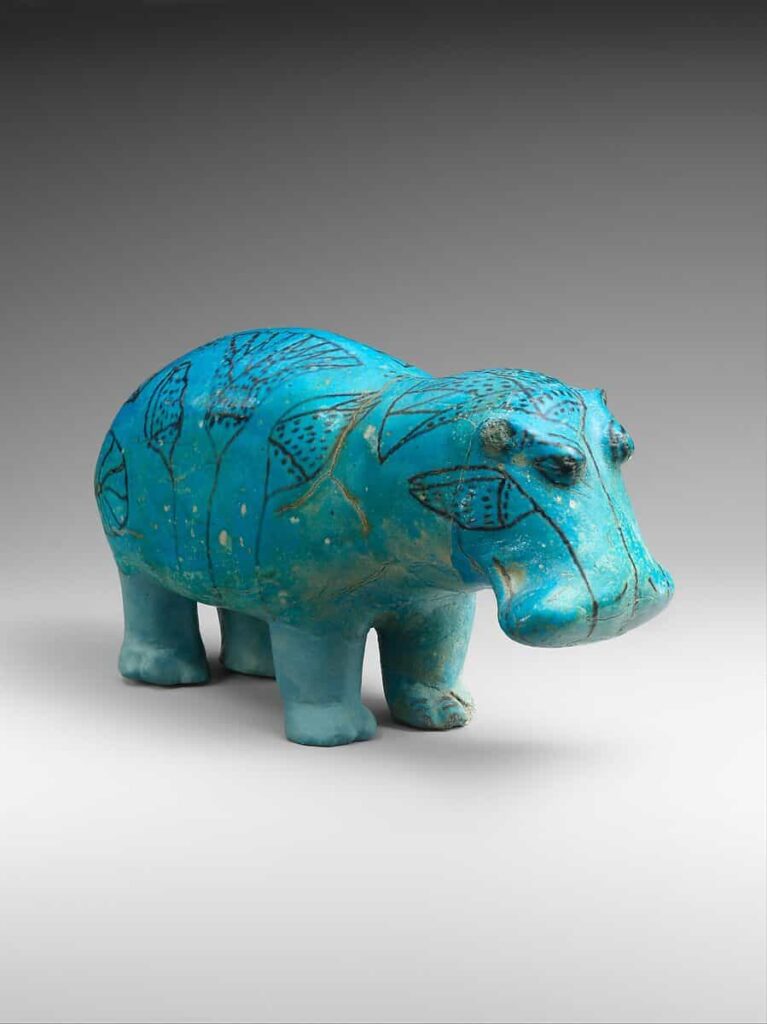

The image of a hippo’s back emerging from the water was reminiscent of land surrounded by the Nile, evoking the primeval mound from Egyptian creation myths. In these myths, the primeval mound emerged from the waters at the dawn of creation, where the sun first rose. Another version of the story describes the sun god appearing atop a lotus flower that emerged from the primordial waters, connecting the mound, the water, and the lotus to life and creation.

The hippo’s daily vocalizations at sunrise and sunset may have been interpreted by the Egyptians as greetings and farewells to the sun. This behavior aligned with the sun’s eternal cycle of rebirth, a journey the deceased hoped to join in the afterlife. Thus, the hippopotamus became linked with themes of life, regeneration, and rebirth. Artistic representations, such as figurines and seal amulets depicting hippos, were believed to possess magical properties that could transfer these qualities to their owners.