To keep track of time and align their agricultural activities with the periodic flooding of the Nile, the Ancient Egyptians created a 360-day calendar and added five extra days called “epagomena.” They also divided the sky into constellations and decans.

The Ancient Egyptians relied heavily on astronomical observations and built their culture around them. The solar cycle was crucial to their daily lives and the functioning of their society.

The god of the sun, Ra, was believed to cross the sky during the day and journey through the afterlife at night, defeating the forces of darkness and being reborn with renewed strength each morning. This cycle of light and darkness, life and death, defined the rhythm of Ancient Egyptian life.

Agriculture was the backbone of the Ancient Egyptian economy. The Nile River, with its yearly flooding and fertile silt, was central to agricultural life. To prepare for these cyclical floods and determine the best times for planting and harvesting, the Ancient Egyptians developed a meticulous calendar.

Sirius Marks the Flooding of the Nile

In Ancient Egypt, there were two calendars: an official religious and administrative calendar, and an agricultural calendar. The official calendar had 365 days divided into twelve months of 30 days each, arranged into three 10-day periods. To better align with the solar cycle, five extra days (called “epagomena”) were added each year. This calendar still had a slight discrepancy with the solar cycle, which was corrected by adding an extra day every four years (leap years).

The agricultural calendar was based on the floods of the Nile. It had 365 days and 6 hours. The appearance of the star Sirius (also known as Sopdet or Sotis) on the horizon marked the start of the yearly flood.

This star is only visible briefly, as it rises with the sun, and its light soon makes it invisible. The first description of this star dates back to the time of Pharaoh Dyer of the First Dynasty, and can be found on an ivory tablet from Abydos.

In Ancient Egyptian art, Sirius is depicted as a seated cow with a plant (representing the year) between its horns. The Pyramid Texts describe Sirius as conjoined with Osiris, giving birth to the morning star. For the Ancient Egyptians, Sirius was the most important star.

The First Calendar

The ancient Egyptian calendar consisted of two types, a civil and an agricultural one, which had a slight discrepancy with the solar cycle. This discrepancy was resolved every 1,456 years, known as the Sothic cycle. The two calendars were synchronized in 139 AD under the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius, marked by a commemorative coin in Alexandria.

The year was divided into three seasons: Akhet (July-October), Peret (November-February), and Shemu (March-July). The first season was the flood of the Nile, followed by the preparation and planting of crops in Peret, and finally, the harvest in Shemu. The reappearance of the star Sirius (Sotis) marked the beginning of the cycle of floods.

Astronomy played a significant role in ancient Egypt, as it was used for timekeeping and orienting religious and funeral buildings. The North Pole and its variations were accurately determined, and names were given to stars, constellations, and planets.

The sky was divided into 36 constellations, or deans, with each one covering 10°. The day was divided into 24 hours, each with its name, and the depiction of a female representation of each hour was common during the New Kingdom period.

Stargazing in Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians used three main instruments for stargazing: the gnomon (a vertical stick that measured the height of the Sun by casting its shadow), the merkhet (similar to a plumb bob and used for lunar astronomy), and the interswing (a forked stick for stargazing).

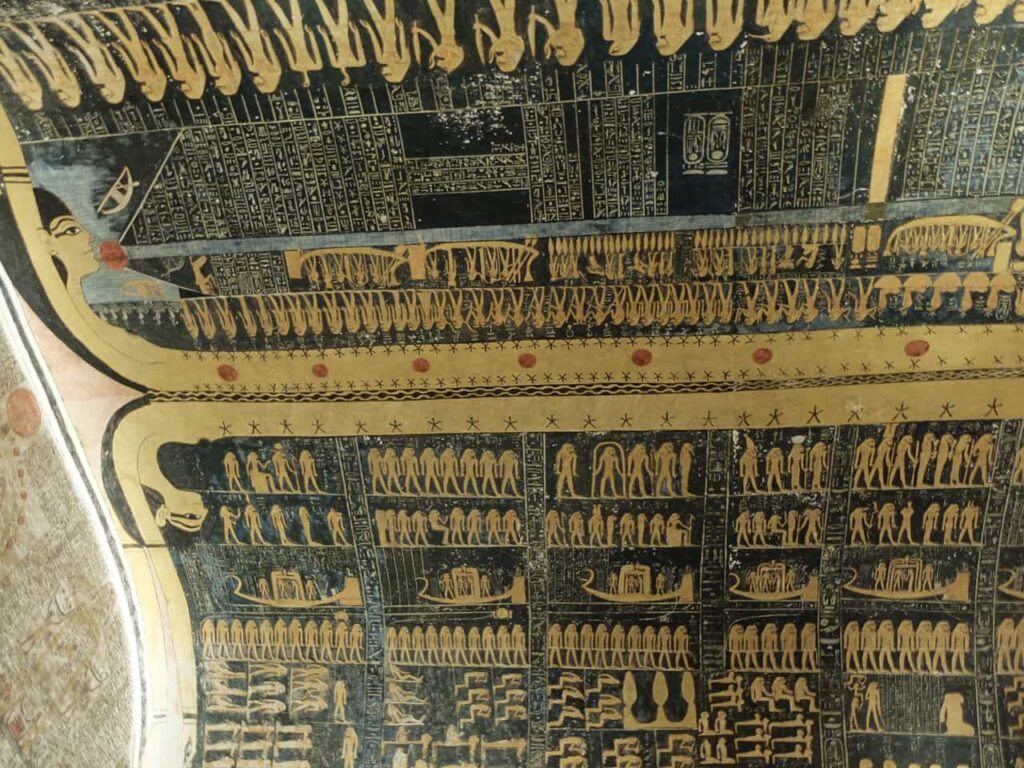

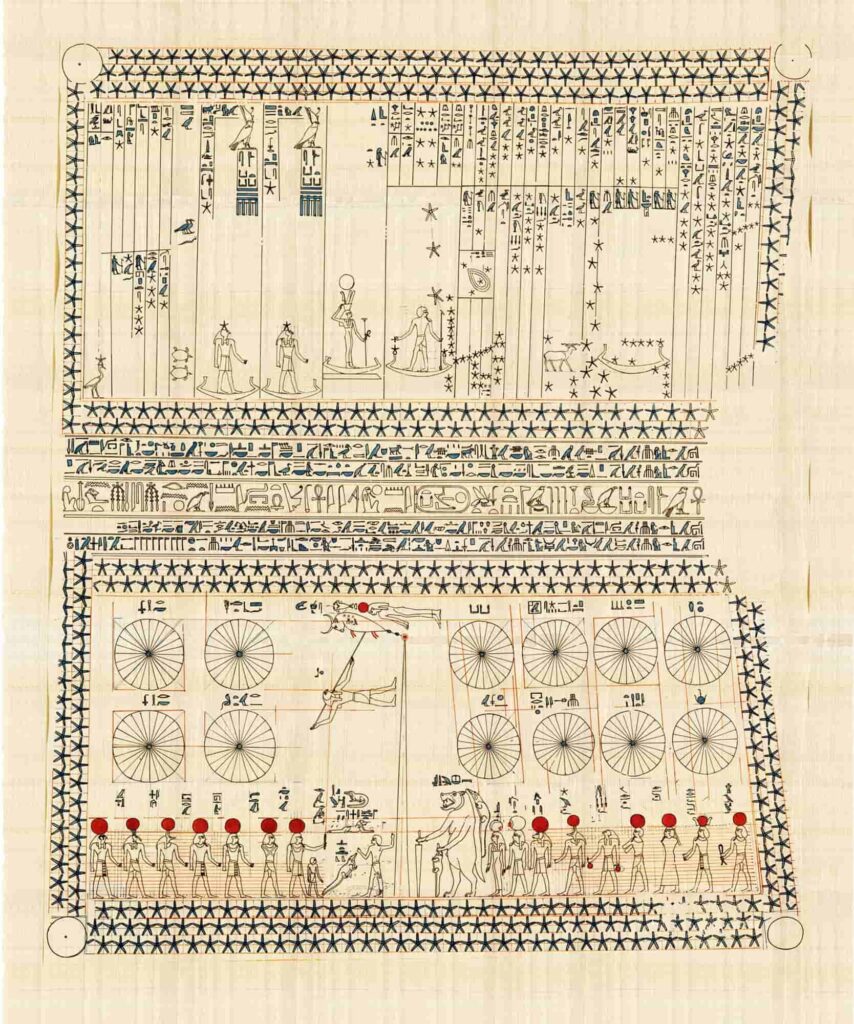

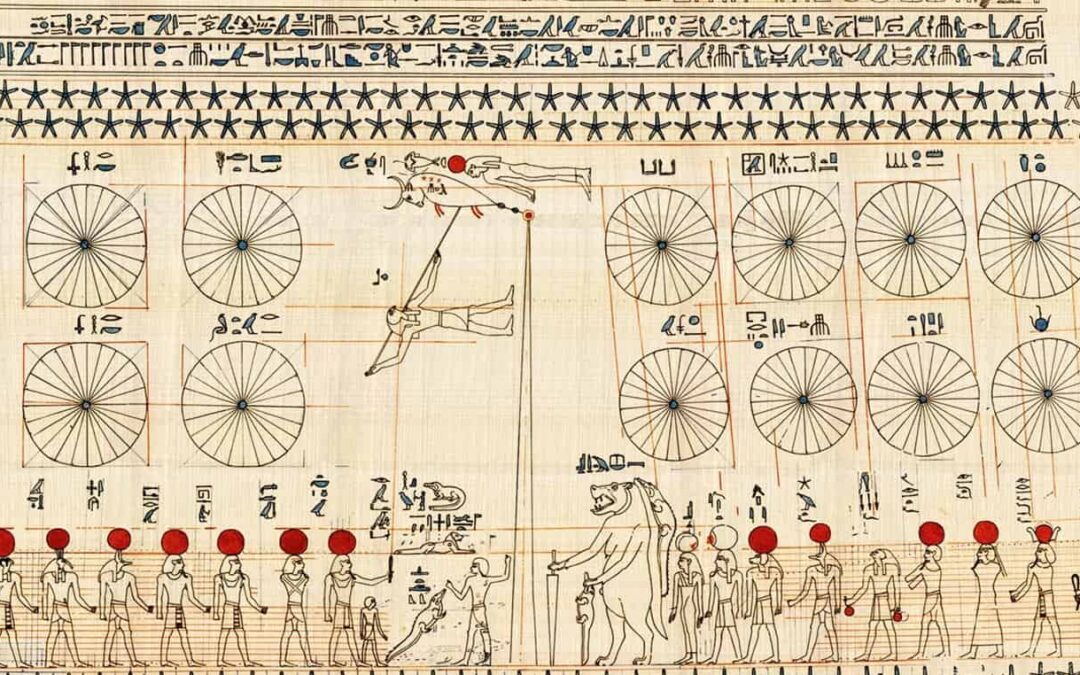

Some tombs from the New Kingdom era feature astronomical depictions on the ceiling, such as the burial chamber in the tomb of Seti I in the Valley of the Kings. One well-known example is in the tomb of Senenmut, the architect of Queen Hatshepsut, at Deir el-Bahari.

The depiction features twelve circles representing the first day of each month, each divided into 24 parts representing the hours of the day. The circles are organized into three sections (the stations) in a rectangle. This symbolizes the renewal of life in the afterlife, just as the cycle of life and death is renewed each year.

Another notable calendar can be found in the funerary temple of Ramses II, the Ramesseum. The temple features representations of the twelve months of the year, the five epagomenal days, the star Sirius (Sopdet or Sothis), the god Thoth (god of measurement, accuracy, and science), and the three seasons.

Source: Marta Saura, National Geographic