Herbert Winlock, the American archaeologist, discovered a fascinating tomb from the Middle Kingdom (2055-1650 BC) in the Theban necropolis of southern Asasif, near Deir el-Bahari.

It belonged to a high official named Meketre who held the titles of “overseer of the seal” and “chief steward” during the reign of Mentuhotep II. Inside, although looted in ancient times, the team found a hidden chamber full of funerary models that offered an unparalleled view of a long-lost world—the world in which the affluent Meketre spent his life.

On March 24, 1920, Winlock’s workers were removing the set of models from Meketre’s tomb when the archaeologist ordered an exhaustive cleaning of the embankment next to the tomb as well as its patio.

When the men reached the highest part of the embankment, “at a place where the rock descended sharply,” according to Winlock in his excavation diary, they found an unexpected surprise: the entrance to what looked like a small, crude tomb that was “blocked with mud bricks.”

An Intact Grave

The door to the tomb was at the end of a tunnel eight meters long and five meters high. Winlock had the entrance photographed and then ordered the bricks to be torn down.

His surprise came immediately when he encountered an intact rectangular wooden sarcophagus, upon which the name of its owner could be read: a man named Wah, a member of the house of Meketre, who held the position of “overseer of the store.”

“Everything was just as the priests had left it four thousand years ago,” Winlock writes in his diary. As soon as he crossed the threshold, there was a bundle of burnt straw from the torch lit during the funeral.

Next to it, on the ground, there was a linen cloth that would have served to cover the coffin on its way to the tomb, and hanging on both sides of the coffin itself were the three linen ribbons with which it would have been tied.

At the foot of the sarcophagus lay the knot of wood with which the lid had been lowered and which those in charge of the burial had sawed once it was fixed in its place.

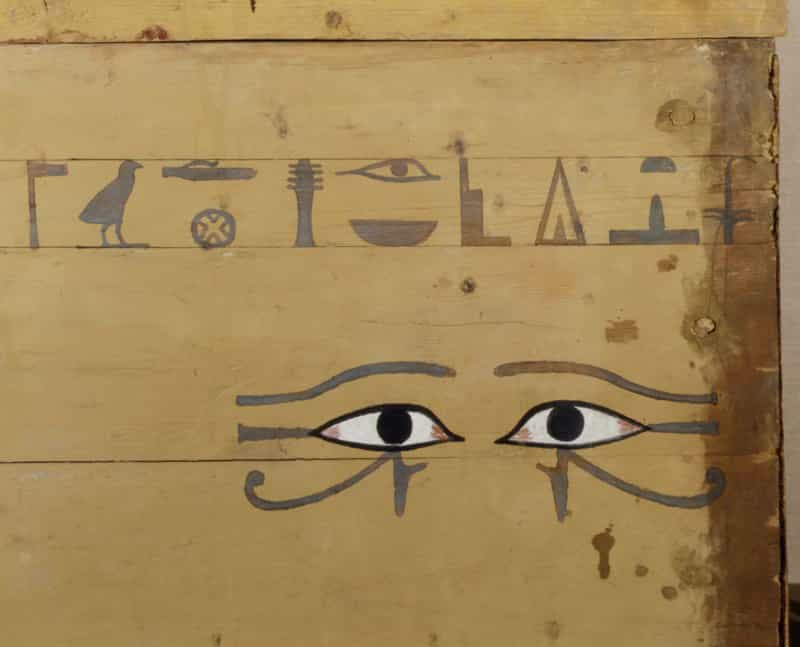

The inspection of that intact tomb provided even more surprises. Winlock verified that eyes had been painted on the sides of the wooden sarcophagus, which would have allowed the deceased to “see.”

Adjacent to the coffin, former mourners had placed twelve slices of bread, the right front leg of an ox, and a mug of beer. Winlock couldn’t help but notice that the latter was identical to the beer mugs depicted in the models he had recently discovered in Meketre’s tomb.

During Wah’s burial, someone had poured a libation with this beer, as a dry crust was still visible on the ground where the liquid had been spilled.

Inside the wooden sarcophagus, archaeologists discovered an intact mummy, wrapped in thick layers of linen, with its face and shoulders covered by a golden mask.

The body had been positioned on its left side, with its head resting on a wooden headrest. Additionally, a resin disc and a copper mirror were found. At the feet of the mummy, a pair of wooden sandals and a statuette of the deceased, also made of wood and wrapped in linen, were discovered.

An Unexpected Surprise

The year 1920 proved incredibly fruitful for Herbert Winlock, who arranged for the mummy and its accompanying materials to be sent to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. For years, it remained displayed exactly as it had been found, with its linen bandages intact and the golden mask covering its features.

Researchers initially presumed that because Wah was not a man of high social standing, merely an employee of Meketre (though a highly valued one, given his close proximity in burial to his master), the bandages likely concealed nothing of great value or interest.

Winlock shared this opinion, stating, “The simplicity of the meal – beer, bread, and meat – at the coffin, as well as the few objects within, made it seem unlikely that there was anything of value inside the coffin.”

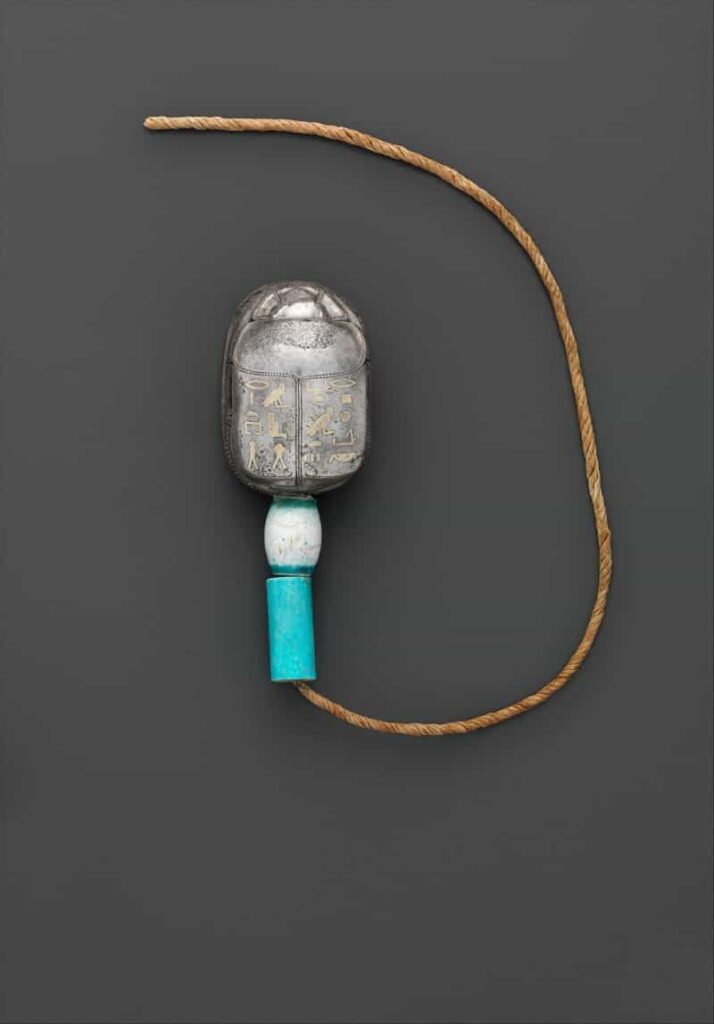

Eventually, in 1939, Wah’s mummy underwent unwrapping (a process that most contemporary researchers currently dismiss) to extract an array of magnificent jewelry. Among these treasures, a stunning silver scarab stood out (it’s worth noting that in ancient Egypt, silver was far more valuable than gold due to its scarcity).

Other discoveries included bracelets, anklets, lapis lazuli scarabs, strings of porphyry and silver beads, and a beautiful turquoise faience necklace.

Further study of the mummy revealed that Wah was taller than average and relatively young at the time of his death, estimated to be around 30 years old. Analysis indicated that at some point in his life, Wah experienced foot problems, likely leading to a more sedentary lifestyle.

Despite the relative richness of his burial, the mummification process applied to his body was notably unsophisticated. This suggests that perhaps Meketre’s admiration for his supervisor wasn’t as high as previously assumed.

Source: National Geographic, Carme Mayans