Ancient Egyptian treasures from the Worcester Art Museum.

The Worcester, Massachusetts Art Museum has among its many masterpieces, a collection of ancient Egyptian jewelry and artefacts that for the most part, haven’t been displayed in almost a century.

The material is remarkable not only for its breadth and quality, but also for its history. The collection was largely given to the museum by Laura Norcross Marrs (1845–1926), the daughter of Boston mayor Otis Norcross and wife of amateur photographer Kingsmill Marrs (d. 1912).

Laura Marrs had a keen eye, not only for jewelry, but also for small, precious things as well, and acquired some pieces of exceptional interest. Some of these included a beautifully carved head of a Nubian out of carnelian, as well as a bracelet spacer of Queen Tiye.

The bulk of the Marrs collection consists of jewellery and amulets ranging in date from the Middle Kingdom to the Greco-Roman period, including necklaces, anklets, scarabs, and amulets.

The Marrses were also interested in the archaeological excavations going on in Egypt.

The Marrs Library at the Massachusetts Historical Society comprises almost a thousand titles, and includes the letters received from Howard Carter.

Mrs. Marrs also donated a number of textiles to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, and a collection of Native American artefacts to the Museo di Storia Naturale in Florence, Italy.

The Worcester Art Museum was particularly fortunate in receiving a vast number of gifts including more than 1400 prints and drawings, and the Marrs’ Egyptian collection. Laura Marrs wrote to Benjamin Stone, the Director of the Worcester Art Museum, on May 21, 1926:

“[I] shall come to Worcester and will bring some very unusual prized scarabs to add to your Egyptian Collection. They are Mr. Marrs private collection of fine workmanship and semiprecious stones numbering around fifty which should make a very beautiful and rare addition to your Egyptian collection.”

Laura Kingsmill Marrs died on September 23, 1926, and was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She was remembered for her remarkable generosity in making bequests to a large number of charities and worthy causes.

Nearly a century after her gift, Laura Marrs’ beneficence will be celebrated in an exhibition showcasing the Worcester Art Museum’s fabulous Egyptian holdings. A small selection of these are shown over the next few pages.

The Worcester exhibition, featuring nearly 300 objects, will open in the Spring of 2022 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the discovery of Tutankhamun’s Tomb.

The Marrses also had some of their Egyptian ornaments set by Boston jewellers into brooches and stickpins. Scarabs were powerful magical amulets in their day and represented the mystery and glory of ancient Egypt to 19th- and 20th-century travelers. This blue-glazed, steatite Egyptian scarab has been set in a winged gold mount.

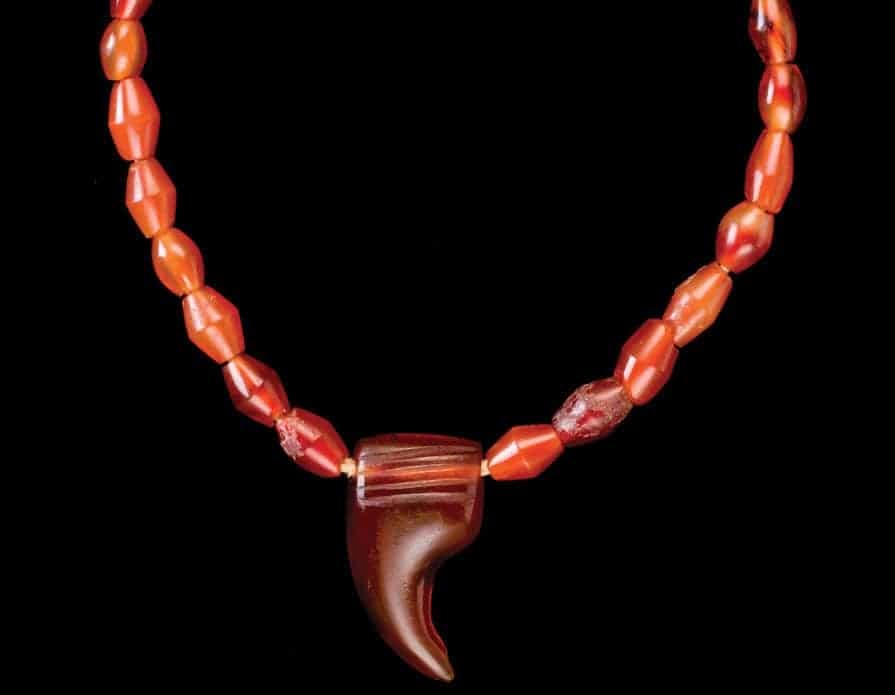

In ancient Egypt young women were often likened to kittens, and anklets such as this, which have an element thought to represent a dew claw, have been found in the tombs of women. A number of pairs of these anklets, in gold or carnelian as in this example, have been found in burials of the Middle Kingdom.

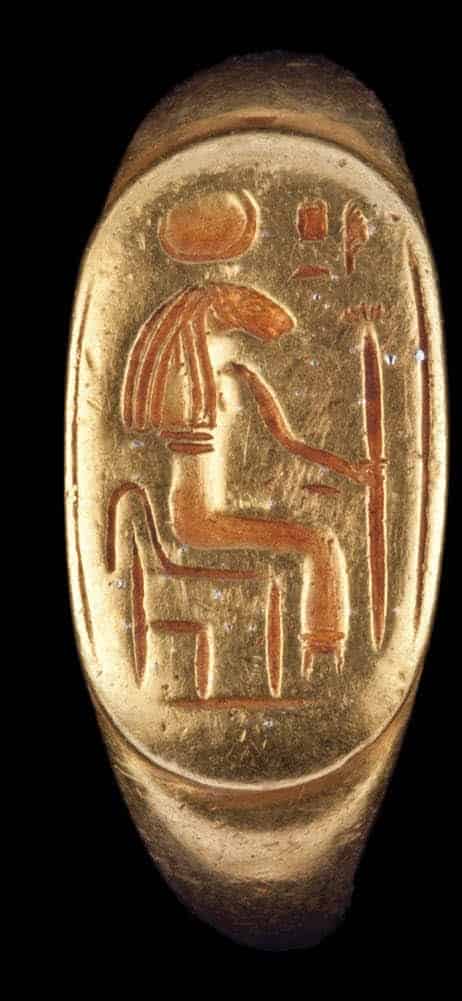

This gold signet ring, dated to the New Kingdom, is chased with a seated figure of the lioness-headed goddess Sekhmet. As the daughter of the sun-god Ra, and the manifestation of his occasional fury, Sekhmet is shown with a sun-disk above her head.

The scattered silver-coloured spots, probably platinumiridium, are characteristic of alluvial gold deposits. It suggests that the gold used for this ring was rinsed from the sand and gravel of river beds, rather than the back-breaking process of mining veins of gold in open pits or galleries. The Egyptians were masters at packing a lot of detail into a tiny space; the face of this ring is just over two centimetres high.

This gold spacer bead inscribed with the cartouche of Amenhotep III’s great royal wife, Queen Tiye, is just 1.9 cm tall and would have come from a bracelet or necklace. The loops would attach to strings of beads and perhaps acted as one half of a clasp to secure the ornament.

The hieroglyphic text on this spacer reads “King’s Wife, Tiye”. She was the mother of Akhenaten and grandmother of Tutankhamun. Mrs. Marrs’ records noted that this piece was reported to have come from the Valley of the Kings.

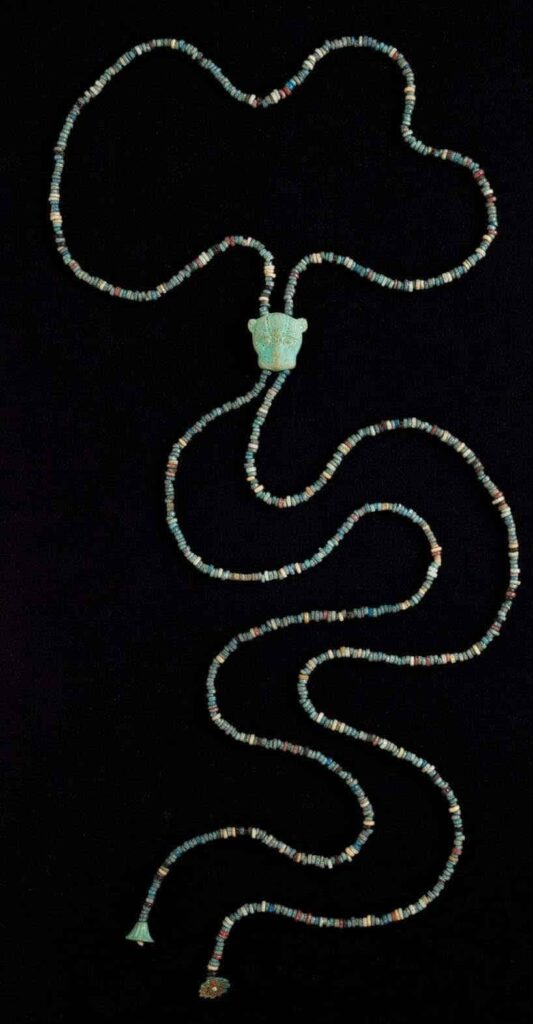

Egypt was the largest producer of beads in antiquity. The quest by Egyptian craftsmen to produce a manmade material that was more readily and easier to work into artefacts reminiscent of stone led to the discovery of faience and subsequently glass.

Both of these materials were considered to be artificial precious stones. This faience bead necklace with a leopard head spacer dates to Egypt’s New Kingdom.

This New Kingdom plaquette has been set in a modern (early 20th century) gold mount, consisting of a skiff with lotus blossoms and buds. The lotus, connected with creation and rebirth, was a popular decorative motif in Egyptian antiquity and one that was also fashionable among revivalist jewellers.

Source: Peter Lacovara, Nile magazine.

Peter Lacovara is director of The Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund. He was previously senior curator of Ancient Egyptian, Nubian, and Near Eastern Art at the Michael C. Carlos Museum.