One of the most impressive archaeological discoveries of ancient Egypt is, without a doubt, that of the so-called “cache” of Deir el-Bahri.

After years of tracking down a family of tomb raiders, the Abd el Rassuls, who had been saturating the antiquities black market for a long time with a huge quantity of pharaonic works of art of uncertain provenance, In 1881, Gaston Maspero, then Director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, and his German assistant, Emile Brugsch, managed to reach an agreement with the family of thieves so that they would reveal the whereabouts of their apparently inexhaustible source of income.

Before the great pharaohs

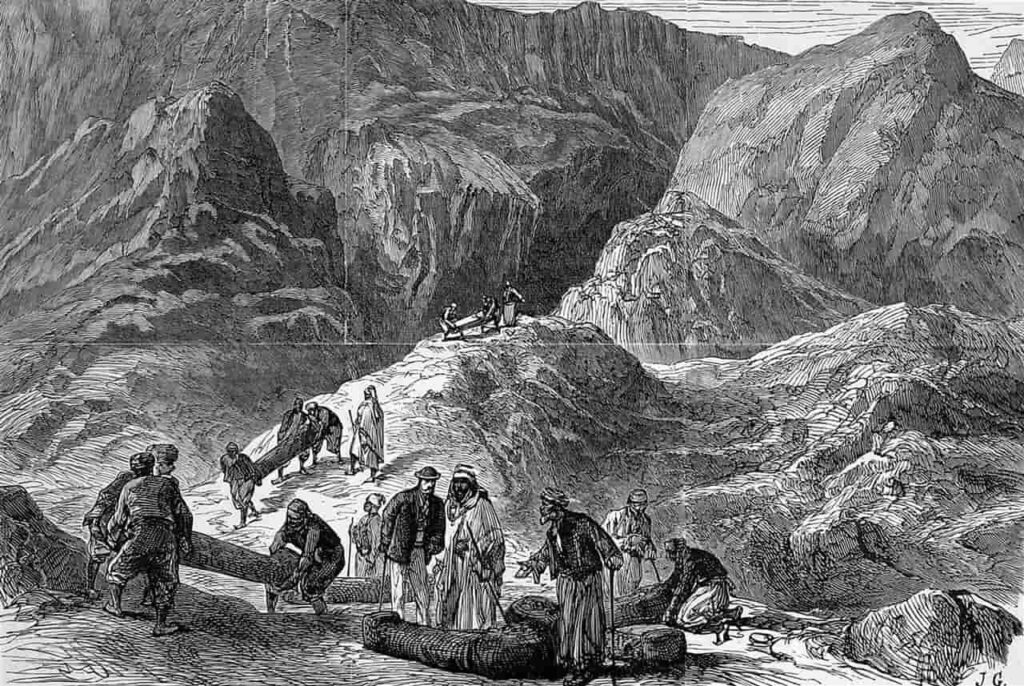

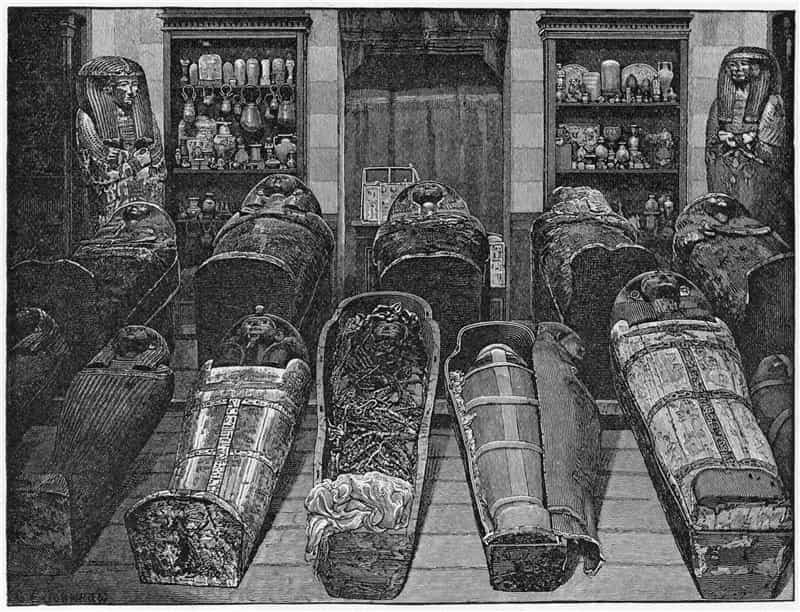

When the Abd el Rassul led archaeologists to the entrance of an ancient tomb carved into the slopes of a Theban mountain (it was made for the priest of Amun Pinedjem II), nothing had prepared them for what they would discover inside:

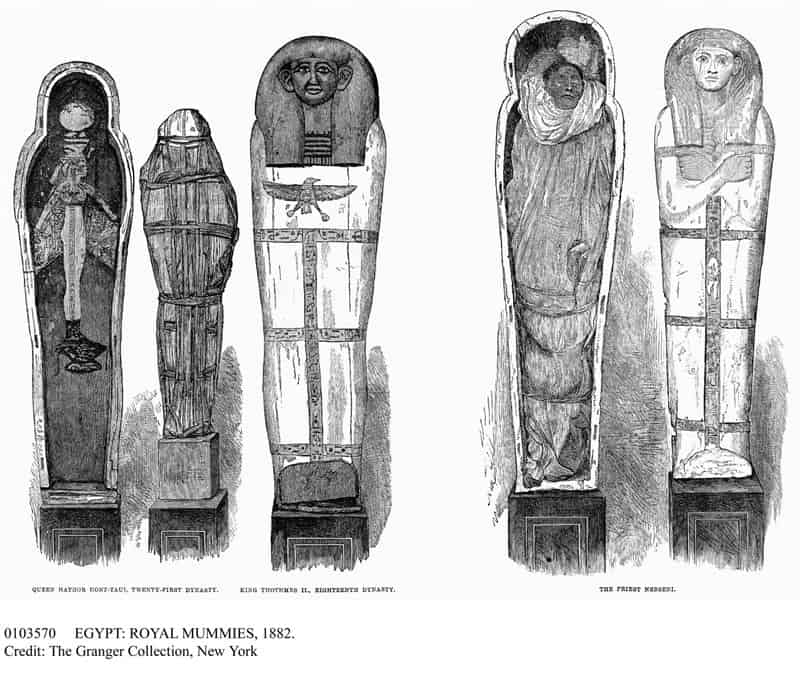

Most of the mummies of the great pharaohs of the 18th, 19th and 20th dynasties (Amenhotep I, Thutmose I, Thutmose III, Ramses II, Seti I, Ramses III…) were found there, carefully placed and bandaged again by the hands of the pious priests of the Twenty-first Dynasty, who rescued the bodies of the former monarchs and queens from their original sepulchres, to save them from certain plunder, in a time of great political instability.

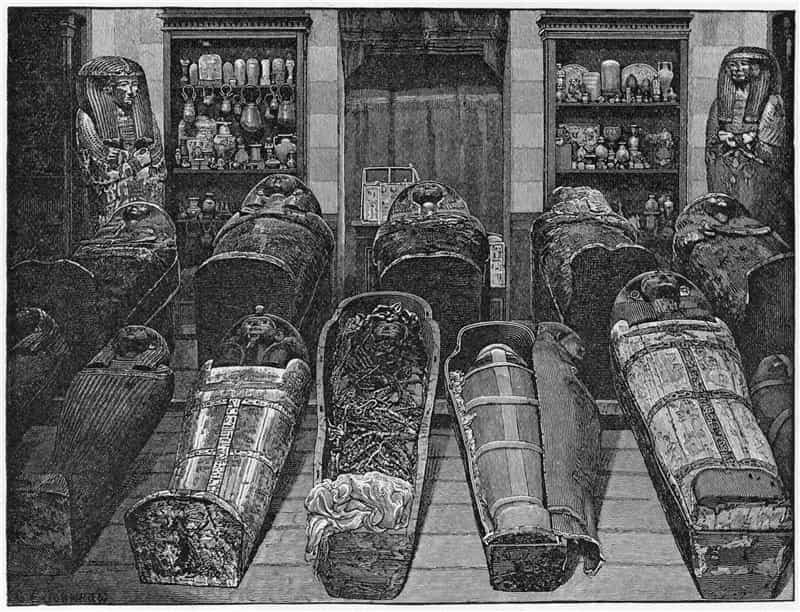

Three hundred workers needed two days to empty the tomb and move the coffins and treasures to a ship that would take them to a safe place in the Bulaq Museum, the predecessor of the current Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Face to face with Ramses

Gaston Maspero thought it would be interesting to organize the unveiling of the royal mummies in order to study them. And the first pharaoh he decided to examine was Thutmose III.

The mummy of the great Egyptian conqueror had suffered a rather rough “treatment” by the Abd el Rassul, who manipulated his body in search of gold amulets and precious stones.

When Maspero finally revealed Thutmose’s mummy, he saw that its state was rather deplorable: its head had been torn off, as well as its legs, and the remains of the resin-soaked linen wrappings that covered it were completely glued to its skin, which made it very difficult to remove.

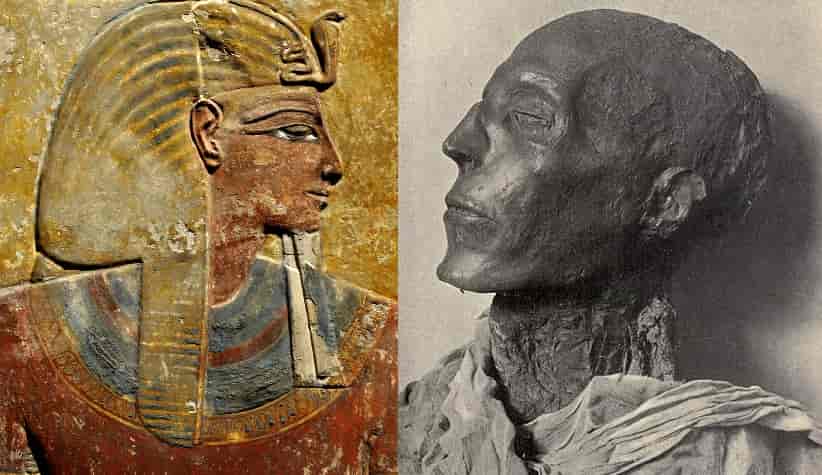

Following this disappointment, it took Maspero a few days to attempt to unwrap another royal mummy. For this he chose the one of the Ramses II. In this case, the researchers were impressed by the well-preserved state of the pharaoh.

According to Maspero, his skin “was an earthy brown color”, his arms were crossed over his chest and his mouth contained a kind of black paste (no doubt remains of the resins used in embalming) that Maspero cut with scissors, revealing the old monarch’s white teeth, still in fairly good shape.

Queen Ahmose-Nefertari

The next to be unwrapped and studied was the mummy of Queen Ahmose-Nefertari, who was the wife of Ahmose I, founder of the 18th dynasty who completed the expulsion of the Hyksos.

But unfortunately, as Maspero himself relates, “as soon as the body was exposed to the outside air, it literally sank into a state of putrefaction, dissolving into a dark matter that gave off an unbearable odor.”

The dry, sterile and hermetic environment inside the cache perfectly preserved the bodies, but exposure to the humid air of Cairo managed to destroy in a short time what the millennia had not achieved.

Ramses III

But Maspero and his team continued tirelessly with the study of the mummies discovered in the cache.

They then chose that of Ramses III, the pharaoh who fought and expelled the Peoples of the Sea from Egypt and who died as a victim of a harem conspiracy.

Archaeologists unwrapped three layers of bandages, cut open a canvas cover covered with a thick lining, and found more layers of linen and canvas underneath.

In the end, the monarch’s face was covered with a bituminous-looking substance that hid his features, “a great disappointment, acutely felt by the archaeologists,” according to Gaston Maspero.

Flowers for the afterlife

In the end there were eight unwrapped mummies in the museum. When archaeologists inspected the body of Amenhotep I, they saw that loving hands had arranged a flower garland around it.

Among the dry cocoons they found an ancient wasp, which was trapped there next to the pharaoh for all eternity. This simple gesture moved Eugène Lefébure, director of the French Institute of Archaeology, who also participated in the unwrapping work.

“Nearly all the mummies were covered with dry garlands (although not all as well preserved as that of Amenhotep I) and withered lotuses that had lain untouched for thousands of years, and there was no better way to understand the suspension of time and the brake on decomposition than to see those immortal flowers on eternalized bodies. It is the image of an endless dream.”

But it was the state of the mummy of Seti I, the father of Ramses the great, that most astonished researchers. One of the participants in the unveiling of the monarch’s mummy described it thus:

“A calm and gentle smile still rising to his lips; from under the lashes his half-open eyelids poke out an apparently wet and shiny line, the reflection of the eyes of white porcelain inserted into the orbits at the time of burial”. The perfect image of that “endless dream” described by the emotional Lefébure.

Source: Carme Mayans, National Geographic