Herbert Eustis Winlock was one of the most successful and active archaeologists during the Golden Age of Egyptology in the early 20th century. As a member of the New York Metropolitan Museum, where he eventually became the director, he participated in several expeditions to Egypt and made significant discoveries.

His most notable discovery is associated with his name, which he made in 1920 while studying the southern Asasif necropolis (a part of the Theban Necropolis) near Deir el-Bahari.

Winlock’s attention was drawn to tomb TT280, an ancient burial ground located in the Theban mountains. The tomb, which had been looted in antiquity, had already been explored by French Egyptologist George Daressy in 1895 and British industrialist Robert Mond in 1902. Winlock set out to “clear the corridors and pits of the tomb in such a way that we could make the map which our predecessors did not.”

Finding at the Last Minute

During the removal and cleaning of the tomb, workers discovered 22 fragments of a wooden coffin with passages from the Sarcophagus Texts, as well as some remains of painted reliefs from a funerary chapel.

They learned that the owner of the tomb was a man named Meketre, a high official who lived during the reign of Mentuhotep II, the 11th Dynasty pharaoh whose temple is located nearby.

One day, when the cleaning work was nearly complete, the expedition’s photographer, Harry Burton (the same one who later photographed the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb), entered the tomb at dusk to bid farewell to the workers. He found the atmosphere “electric with pent-up excitement.”

Apparently, one of the workers had seen how some stones slipped and disappeared through a crack between the floor and the wall. The man informed his supervisor, and they both scratched other stone fragments that were piled up on the spot, some of which also disappeared through the hole. Burton moved closer and struck a match to light the cavity, but could see nothing.

Intrigued, the photographer alerted Winlock to come immediately with flashlights. Tired from a hard day’s work, Winlock was reluctant but eventually agreed to take a look. Once in the tomb, he stretched out on the floor and focused a beam of light into the opening without much conviction.

To his surprise, the flashlight revealed “a myriad figures of brightly painted little men doing this and that.” Later, the archaeologist would describe the moment of discovery in this way: “A tall and slender girl returned my gaze with perfect composure. Little men with sticks in their hands drove dappled oxen; rowers manned their oars in a fleet of boats, while one vessel seemed to capsize right before my eyes with its prow balanced precariously in the air. And everything took place in the most absolute silence.”

Millennial Footprints

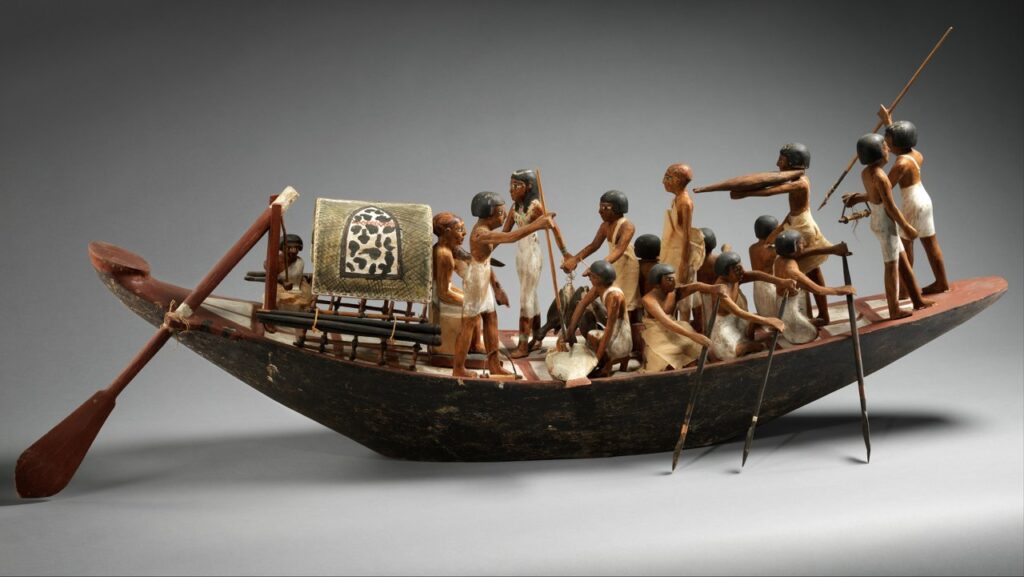

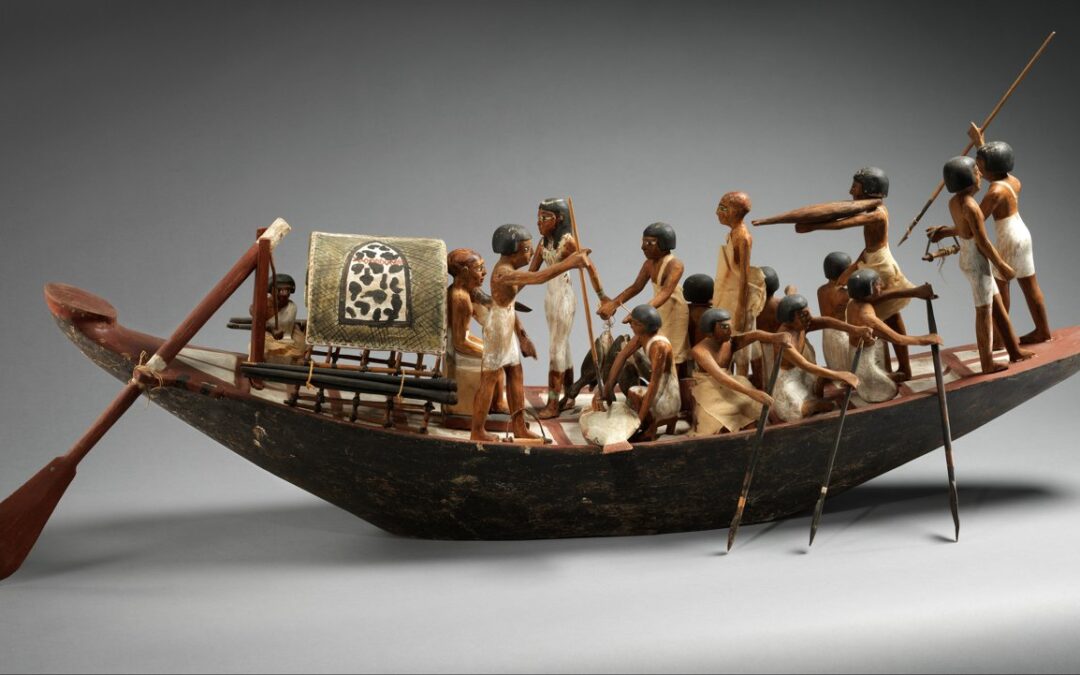

The following day, the archaeologists entered the room. They discovered that it was not a burial chamber but a tiny room where twenty-four small painted wooden boxes had been deposited. These boxes represented workshops and courtyards where cattle herders, butchers, bakers, brewers, spinners, weavers, carpenters, and scribes moved.

They were all hard at work, offering a glimpse of what daily life was like on the Meketre estates. Ten model ships surrounded the boxes, indicating that Meketre enjoyed leisurely trips down the Nile.

In one of them, he appeared seated with his young son and a singer, and in another, a blind harpist entertained in the evening. All of this was intended to recreate Meketre’s peaceful and comfortable existence in the afterlife.

Winlock noted that some figures were broken. For instance, a fisherman was missing an arm, some boats showed scorch marks or had split masts, while certain models had been gnawed at by mice and some had fly and spider stains.

Although archaeologists found no evidence of the presence of these animals inside the chamber, it is possible that Meketre had his tomb models made long before he died and kept them somewhere in his house, where they suffered damage.

The archaeologists, barely able to stand in the cluttered room, carefully removed the model boats and boxes full of figures to take them outside. Only Winlock and a member of his team touched the objects, their hands wrapped in handkerchiefs so as not to damage them.

Once under the hot Egyptian sun, Winlock had one last and emotional surprise: he saw that the models were full of fingerprints… And they were not his own, but those of “the men who had moved them to the tomb from the house in Thebes four thousand years ago and had been left there for their long rest.

Source: Carme Mayans, National Geographic