The Battle of Waterloo was the last battle of the Napoleonic Wars in which the ambitions of the French Emperor were seen to be crushed at once.

Despite his long-standing genius in the campaign, Napoleon was unable to defeat the Allied armies, and the Prussians finished determining his fate by coming to the aid of Wellington on June 18, rather than backing off after his setback at Ligny.

The Battle of Waterloo summary

Who defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo?

Emperor Napoleon (1769-1821) with 72,000 men from the French army attacked an Anglo-Dutch army of 60,000 men under the command of the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852), who was joined by the Prussian army of Prince Gebhard von Blücher that afternoon.

How: In a superb defensive battle, Wellington’s army was able to fight back, with great difficulty, Napoleon’s attacks until the arrival of the Prussian army.

Where was the Battle of Waterloo?

The crest of Mont St. Jean, near the town of Waterloo, 16 km south of Brussels (Belgium).

When was the Battle of Waterloo?

June 18, 1815.

Why:The flight of Napoleon from Elba and the restoration of the empire could not be tolerated by the allies, who were trying to crush this threat against European peace.

Who won the Battle of Waterloo?

The defeat of Waterloo forced Napoleon to his second abdication, after which he was finally exiled at St. Elena, in the South Atlantic.

Revolutionary and later Napoleonic, France had been fighting Britain and its allies for 20 years when, finally, Napoleon abdicated in April 1814 and was exiled to the island of Elba.

However, discontent in France with the Bourbon king, Louis XVIII, led Napoleon to risk a journey with 1,000 men from the island to France, where he landed on March 1, 1815..

Louis was forced to flee to Belgium as the allies began to mobilize their armies. Napoleon sincerely wanted peace, but the other European powers would never allow him to threaten them again.

The French were weary of war and bloodshed, as were the soldiers and officers, and even Napoleon’s own marshals were reluctant to fight.

This especially applied to marshal Ney, who detested Napoleon. Ney, who had first promised Louis to bring Napoleon back in an iron cage before going over to his side, felt deep inside that Napoleon was a depleted force and that France, faced with a hostile European coalition, could not prevail.

Unfortunately for Napoleon, his irreplaceable chief of staff of the old days, Marshal Berthier, had been killed in an accident, and his replacement, Marshal Soult, was not so talented.

The combination of Napoleon’s physical and mental decline, coupled with the awkwardness of his subordinates Soult and Ney, would lead to defeat at Waterloo.

The Anglo-allied army

On the opposite side, Wellington did not have it easy either. Its peninsular veterans were scattered around the world or had been demobilized.

Consequently, Wellington was reduced to fighting Napoleon with a motley army of Dutch, Belgian, and German mercenaries (from Hess and Nassau) and with a small force of English soldiers..

He had 68,800 infantry and 14,500 cavalry, which, with other troops, added a total of 92,300 soldiers divided into three infantry corps under his command, that of General Hill and that of the Dutch Prince of Orange.

The cavalry was under the command of the Earl of Uxbridge, who also acted as Wellington’s lieutenant. Relations between the two were cold (Uxbridge had eloped with Wellington’s sister-in-law) and he had been appointed against Wellington’s obvious wishes.

The Allies therefore relied on the Prussians, with 130,000 men, to contain Napoleon.

Their legendary commander, Field Marshal and Prince Gebhard von Blücher (1742-1819), might never have been the greatest strategist, but he could be trusted to fight the French and to come to the aid of Wellington, who he hoped that Napoleon would attempt to wedge his separate armies.

The Battles of Quatre-Bras and Ligny

On June 15 Napoleon crossed the Belgian border with 123,000 men from his “Army of the North” through Charleroi, exactly where Wellington had not expected him to attack.

Wellington rushed to the aid of his soldiers, who were holding Marshal Ney at the crossroads of Quatre Bras.

Ney had shown unusual apathy by ceasing to occupy this vital position, compounding this error when he did not start the battle until the afternoon, and then using 4,000 cuirassiers to charge against the English infantry.

Obviously Ney completely lost his memory when he repeated this mistake three days later in Waterloo: charging against intact infantry formations without the support of his infantry.

The same day, On June 16, the central battle took place at Ligny between Napoleon’s main army of 71,000 men and Blücher’s 84,000 Prussians..

The Prussians had decided to scatter over swampy terrain, but Napoleon was not at his best tactical moment either. He delayed the battle until the afternoon, when he was forced to simply crush the Prussian lines to subdue them.

For nearly two hours, the savage fighting continued, frequently melee, with bayonets and firing at point-blank range. Prussian losses totaled 19,000, and although Blücher left the field, Napoleon had suffered heavy losses (about 14,000 men) that he could hardly afford.

Napoleon sent Marshal Grouchy in pursuit of the Prussians with 30,000 men, but the latter did not press closely on the enemy and, far from retreating back to Germany, Blücher marched west to support Wellington, as he had promised.

After defeating the Prussians, Napoleon headed for Quatre Bras, where he found that the English, after containing Ney’s attacks, withdrew from the battlefield in an orderly method, without any effort on the part of the French to pursue or harass them.

Instead, Ney and his staff sat down to dinner. Napoleon could not believe what his eyes were seeing, and he gave his officers a violent scum that, although deserved, did not contribute to raising Ney’s morale.

Mont-Saint-Jean

The next day there was a much-needed pause as Wellington’s army, numbering 74,300 soldiers, took up positions around the Mont St. Jean farm and the town of Waterloo, where Wellington established his headquarters.

** Wellington was facing to a French army of 74,500 men who had camped south of the Brussels highway, while Napoleon had established his headquarters at the inn of the Belle Alliance **.

The two armies were very numerically equal. This, however, did not take into account the qualitative differences between the two armies.

Napoleon’s soldiers were seasoned veterans, while Wellington’s troops had recently been recruited, and only 28,000 of them were English.

Furthermore, the French not only had more cavalry and artillery, but they were of a much higher quality than Wellington’s.

Not only did the 12-pound French guns have a longer range than the 9-pound English guns, but the servers serving them had more experience and better controls.

What happened in the Battle of Waterloo?

As a battlefield, that of Waterloo, compared to that of Borodino (1812) in Russia, was very compact and dense, and intense action was to take place over the course of a single day. One day, June 18, which would forever change the course of European history.

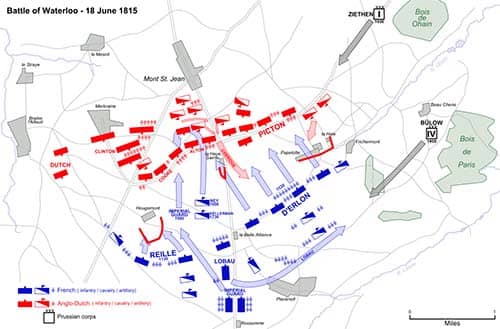

Wellington had formed his army on the basis of divisions divided into three corps.

The end of his left flank was defended by the German division of the Prince of Saxe-Weimar, supported by the Uxbridge cavalry behind him.

On the opposite side was the Dutch and Belgian division of the Prince of Orange, then came the Clinton division (behind the Braine l’Allend road), the Cooke division, at the confluence of the Brussels road the division of Alten (opposite La Haie Farm) with the Wellington Reserve Corps and finally lined up along the Ohain Road, General Picton’s division.

Napoleon’s army was lined up along a line parallel to Wellington’s, perpendicular to the Charleroi to Brussels highway, with the left flank on the Nivelles highway.

Piré’s cavalry was on the far left, with Kellerman’s III Cavalry Corps and the guard cavalry, under the command of Guyot, in the rear, while Prince Jerome Bonaparte’s infantry was in front of the walled estate of Hougoumont.

The center consisted of the Army Corps I divisions of General and Count JB d’Erlon, with Milhaud’s cavalry behind. The right flank was supported in the position of La Haie.

Faced with the possibility of Blücher intervening at any moment, Napoleon had to make the first move and achieve a swift and decisive victory over Wellington before having to turn and face the Prussians.

If the two armies came together, it would be the end, not only for their army, but also for their restored empire.

Interestingly, Napoleon’s plan, as in Borodino in 1812, was unimaginative and relied on the use of brute force in a frontal attack rather than trying to tactically outwit the Allied army.

Napoleon simply intended to break the Wellington line through the La Haie Sainte farm in the center and occupy the crossroads behind, continue to advance, and occupy the Mont St. Jean farm.

The battle begins

Napoleon had prepared the attack for 10.30, but a downpour fell during the night, leaving the ground too soft for cavalry and artillery fire.

The main assault was postponed, with fatal consequences, until 1 pm, and the French launched a preliminary artillery bombardment at 10.50 am against Hougoumont Castle to the right of Wellington, defended by the harsh Hanoverian soldiers of the German King’s Legion and by a detachment of Nassau troops.

To divert Wellington’s attention from his left flank, where Napoleon’s main attack was to be launched, he ordered his brother, Prince Jerome, to attack Hougoumont, to attract Wellington’s reserves..

However, the prince sent wave after wave of his infantry against the firmly defended estate, to little avail, holding his own troops while Wellington sent only minimal reinforcements. He released his full four regiments and half of Foy’s division in addition.

It was vital for Wellington to defend this crucial turning point at the front line at all costs, so he dispatched his most seasoned soldiers, the Coldstream and Scottish guards, to back up the German defenders.

At one o’clock in the afternoon, while Napoleon was preparing to attack, a messenger brought the bad news that the Prussian corps under the command of General Bülow (30,000 men) was approaching from the direction of Wavre.

A cautious man would have withdrawn; However, Napoleon bet that Grouchy, who was supposedly on his way to the battlefield, would take an hour to arrive and intercept the Prussians; It took four, and by then the Prussians had helped Wellington defeat Napoleon.

As an additional guarantee against the appearance of the Prussians, Napoleon placed Count Lobau, with 20,000 men, on his right flank, facing east and the Prussians. Although it was a sensible move, it also meant a considerable weakening of the main attack on Wellington.

D’erlon attack

At 1:30 PM, about 84 cannons located in the Belle Alliance opened fire during the next half hour. Because the ground was soft and wet, this fire was ineffective, as the bullets hit the ground and sank, rather than ricocheting off the Allied infantry.

Even if they had, Wellington had positioned most of his soldiers a little behind the ridge, rather than on it. It was not until 2:00 PM that Napoleon launched Army Corps I from D’Erlon.

The latter, hoping to pierce the Allied lines by mere numerical weight, formed his divisions into three huge columns of battalions spread out one after the other.

Although highly vulnerable to allied artillery and musketeers in this formation, the avalanche of blue-clad infantry proved almost irresistible, once the Corps I assault was launched, sweeping aside the unprotected 1st Brigade of the Netherlands (Dutch and Belgian) by Van Biljandt.

Wellington’s center-left position collapsed under this huge wave of attacking infantry, forcing him to send as many soldiers as he could do without.

The best he had was Sir Thomas Picton’s 5th Infantry Division (6,745 men) made up of English (8th and 9th Brigades) and Hanoverian (5th Brigade) troops.

Picton’s fierce counterattacks, backed by the Uxbridge cavalry, including Sir William Ponsonby’s 2nd Brigade (Union), contained the French; although with difficulties, and with an enormous cost.

Both Picton and Ponsonby died, Uxbridge lost a leg from a gunshot, while approximately 40% of his men were left dead, captive, or wounded.

However, his sacrifice was worth it, as the French attack stopped dead. They began to withdraw, eventually fleeing and leaving some 3,000 prisoners in the hands of the English. An hour later (around 15:00) the English had defeated the first French assault.

Ney’s cavalry attacks

At 15:30 Napoleon ordered his artillery to beat La Haie Sainte and Ney to prepare a new assault that he would conduct in person.

However, without informing Napoleon, Ney ordered 5,000 horsemen of his cavalry to attack what he believed to be retreating enemy soldiers; but Wellington was simply putting some of his units out of range of the artillery and rearranging the rest.

Lacking the support of the infantry and artillery, Ney’s cavalry launched their assault to face a hail of artillery and heavy musket fire at close range.

Hundreds of horsemen perished as the English infantrymen (formed into squares for their defense) repelled wave after wave of cuirassiers, dragons, and spearmen coming toward them.

Ney withdrew, regrouped and charged again, and failed again in his attempt to break the English.

At 17:00. General Francois Kellerman joined the attack with his Cavalry Corps III.

Neither Ney nor Kellerman had considered asking Napoleon for permission before launching after the “retreating” Allied troops.

The intensity of the fight was such that Ney lost four horses, killed under the saddle, while some of the English squares were close to the limit after Kellerman’s addition.

However, it was all in vain and around 18:00 even Ney was fed-up and simply walked back to the French ranks after his last horse was wounded.

Napoleon could not believe what Ney had done, or that Wellington’s “half-breed” soldiers had been able to resist this onslaught. To atone for his reckless action, Ney finally took La Haie Sainte, defended to the end by the KGL.

After losing the 2nd Regiment and its commander, Baron Ompteda, they had been unable to do so and withdrew with the broken Hanoverian 1st Brigade. Downtown Wellington was in a state of near collapse, threatening to undo his entire army.

The final attack

The Prussians had begun to appear on the edge of the battlefield around 16:00, and an hour later Napoleon was forced to reinforce Lobau’s Army Corps VI (now reduced to 7,000 men) by sending 4,000 men of the Young Guard.

By 19:00, Von Zeithen’s Corps I had arrived to support Bülow’s men. In a last attempt to pierce the center of Wellington, Napoleon ordered the Old Guard, soldiers who had never been defeated, to attack in two columns of 75 men in the background.

Once again, the English soldiers, hidden behind the ridge, were able to surprise the columns before they could be deployed in line, and destroyed them with musket fire at point-blank range.

When the Old Guard withdrew, the morale of the French army was finally broken, and the soldiers broke up and fled, shouting “Sauve qui peut!”: “Save yourself who can!” and “Trahison!”: “Treason!” . Napoleon fled on a stagecoach and at 20:30, Wellington met his savior Blücher at The Belle Alliance.

How many soldiers died at the Battle of Waterloo?

The French had lost 25,000 men. Wellington had lost 15,000 and the Prussians 6,700. At 5:00 the next day, Napoleon was back in Charleroi, on his way to Paris.

On June 22 he abdicated a second time, fled Paris, and on July 15 he boarded the HMS Bellerophon in Plymouth. Four months later, he landed on the island of St. Elena, his “home” until his death.