In a story written in 1941, the Argentine writer, Jorge Luis Borges, imagined a “universal” or “total” library, where all books produced by man would be gathered.

Its endless hexagonal shelves would contain “everything that can be expressed, in all languages,” works that were believed to be lost, volumes that explained the secrets of the universe, and treatises that resolved any personal or world problem.

Without a doubt, the model of that literary dream is found in the famous Library of Alexandria.

Created a few years after the founding of the City by Alexander the Great in 331 BC, its purpose was to compile all the works of human ingenuity across all times and countries and should be “included” in an immortal collection for posterity.

By the middle of the 3rd century BC, under the guidance of the poet Callimachus of Cyrene, the Library is believed to have held close to 490,000 books, a figure that had risen to 700,000 two centuries later, according to Aulus Gellius.

These are disputed figures –other more prudent calculations take a zero off both– but they give an idea of the significant loss of knowledge caused by the destruction of the Alexandrian Library.

The complete disappearance of the extraordinary literary and scientific heritage that librarians such as Demetrius of Phalerum, the aforementioned Callimachus, or Apollonius of Rhodes knew how to hoard over decades.

The disappearance of the Library of Alexandria undoubtedly constitutes one of the most symbolic cultural disasters in history.

The First Destruction

It is difficult to pinpoint the exact moment when the destruction of the Library of Alexandria occurred. The fact is shrouded in myth and darkness, and it is necessary to investigate the sources to get an idea of the sequence of events.

The first information about it dates back to 47 BC. In the war between the claimants to the throne of Egypt, the Roman general Julius Caesar had come to Alexandria to support Queen Cleopatra.

He was besieged in the fortified palace complex of the Ptolemies in the Bruquión neighborhood, which overlooked the sea where the Library was likely located along with the Museum.

Caesar bravely defended himself in the palace, but a fire broke out in the armory and spread to a section of the palace during one attack.

Numerous books would have been burned that Caesar himself intended to transport to Rome –sources speak of 40,000 scrolls. Some even claimed that the entire Library burned down.

This last extreme is not plausible, mainly due to the magnitude that this fire would have had on the palace itself.

In any case, it is said that years later, Mark Antony, while in Alexandria with Cleopatra, donated many books from the rival library at Pergamum, perhaps to compensate for earlier destruction.

Decline Begins

With the fall of Antony and Cleopatra, and the consequent collapse of the Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt falling to Rome, Alexandria was entering a slow and inexorable decline and, with it, its Library.

Certainly, it continued to attract students and scholars, such as Diodorus Siculus or Strabo, and its fame went beyond borders.

But there was no longer a royal court of its own, and the Egyptian city was losing momentum to Rome, the capital of the Empire.

The various crises of the second century, such as the terrible Antonine plague that devastated Egypt, and especially of the third century, full of political usurpations and serious conflicts, had very negative repercussions on the cultural life of the City and the conservation of the library’s books.

To add insult to injury, in the year 272 AD, Emperor Aurelian laid waste to Alexandria during his campaign against Queen Zenobia of Palmyra.

Years later, under the reign of Diocletian, the City suffered another major devastation that affected the palace complex.

The proclamation of Christianity as the official religion of the Empire in the fourth century had more serious consequences for the Alexandrian Library.

Its shelves had compiled the knowledge of classical paganism, precisely the type of culture that some Christian movements rejected.

Inevitably, the old books of the Ptolemaic library ceased to interest the adherents of the new religion. But that was not all. The laws against paganism promulgated by the emperor Theodosius were used by the most holy Christians to legitimize their attacks against temples and institutions of paganism.

In this way, the important library of the Serapeum, the foundation of Ptolemy Euergetes –which some authors confuse with the Royal library, the Library of Alexandria itself– was razed to the ground in 391 AD.

Years later, in 415 AD, the philosopher and scientist Hypatia of Alexandria, perhaps the last representative of the Alexandrian philosophical tradition, died, and her valuable Library disappeared.

Around that same time, the Hispanic theologian Orosio reported that when he visited the City, he only found empty shelves in the temples, despite the bookish fame of Alexandria.

If the Library had not completely disappeared, there is no doubt that its decline would have become more acute in the following decades.

Violence shook the City again and again, with constant wars and clashes for power. At the beginning of the 7th century, the bloody dispute over the throne of Byzantium between the usurper Phocas and the future emperor Heraclius left a trail of destruction in Alexandria.

In 618 AD, following the conquest of Egypt by the Persians of Chosroes, the damage was not minor, although Heraclius managed to recover the City and all of Egypt for Byzantium.

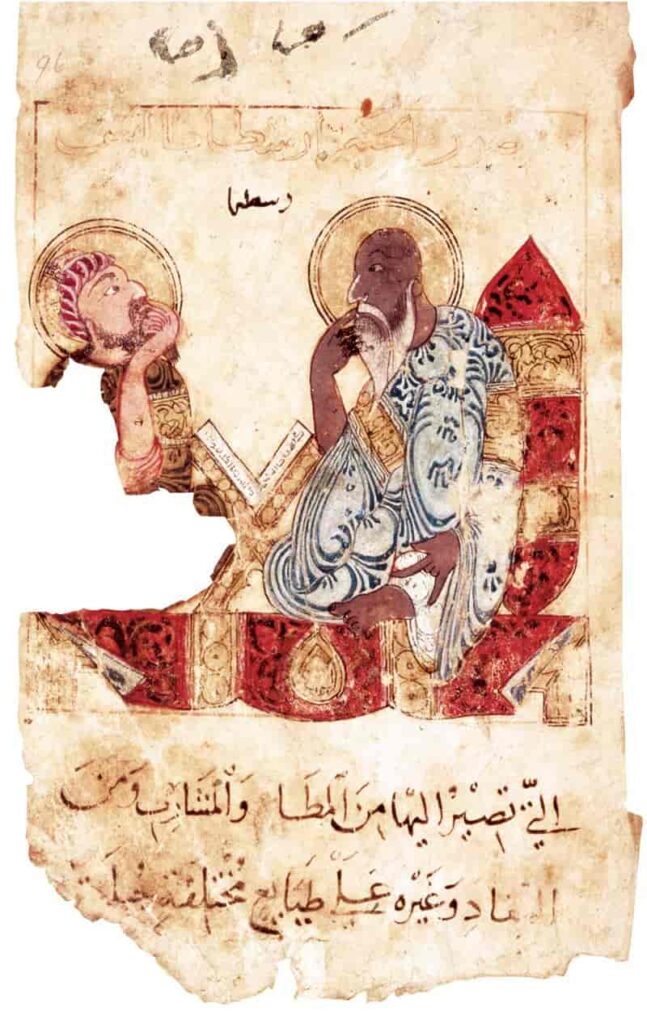

Alexandria itself was captured by a Muslim army commanded by Amr ibn al-As. Some authors believe that the Library progressively disappeared and that when the Muslims arrived, there was hardly anything left. Although, it is possible that there were many new books on Christian theology, along with others of greater antiquity, such as the Aristotelian works to which Philoponus himself referred to supposedly managed to save.

Source: David Hernandez, National Geographic

The Library of Alexandria. School Hippolytus. Gredos, Madrid, 2001.

The missing library. Luciano Canfora. Trea, Asturias, 1998.

Poets, philosophers, grammarians and librarians. Juan Jose Riano. Trea, Asturias, 2005.