When delving into the history of 2,000 or 4,000 years ago, researchers encounter numerous biases, from their subjective interpretations of the findings to the challenge of discerning the hidden intentions of minds from ancient societies.

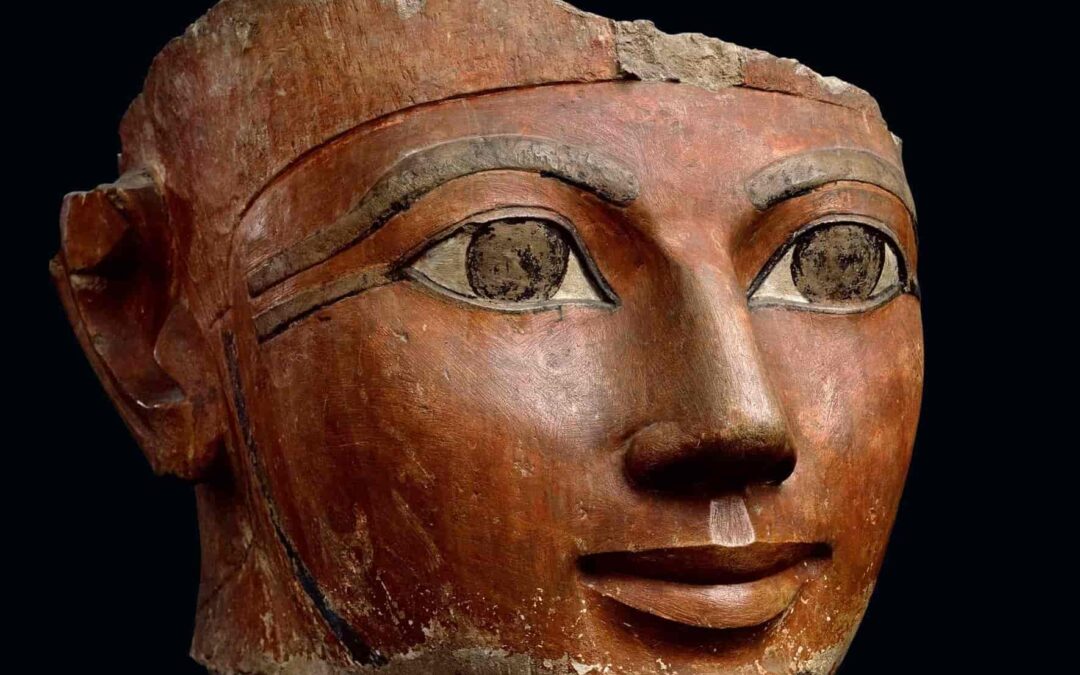

One figure particularly affected by this subjective interpretation of history is the ancient Egyptian queen, Hatshepsut. Her ascension to the throne and her reign for 22 years (around 1479-1458 BC), along with depictions of her with a male body and beard, as well as the subsequent campaign to obliterate her memory through defacement of engravings and destruction of statues after her death, led to her being portrayed as a villainous and manipulative ruler, driven by an insatiable thirst for power, accused of usurping the throne from Thutmose III, her husband’s son from another woman.

For decades, she was regarded by many historians as the most nefarious among the five queens of ancient Egypt. However, modern understanding paints a different picture.

One argument used to justify her vilification is that the other four Egyptian queens ruled for shorter durations, yet little information exists about them to make informed assessments.

“Nitocris, the first queen, is believed to have reigned for only two years (from 2183 to 2181 BC), and scant information about her rule has been discovered,” explains Sabah Abdel-Razek, director of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, in an interview with “La Vanguardia”. This enumeration of queens excludes Cleopatra, who belonged to the Ptolemaic dynasty.

Neferusobek followed, reigning for four years (from 1777 to 1773 BC), yet precise data about her rule are scant, aside from the rivalry with her brother for the throne, which ended with his demise.

As for Nefertiti, she has long been revered due to the limited information available about her; she ruled for a brief period (1340 BC) until she was succeeded by Tutankhamun, her son-in-law, who ascended the throne as a child of about 8 years old.

“The discovery of Tutankhamun’s mummy also heightened the prominence of this queen,” emphasizes Abdel-Razek. Lastly, Tausert, the fifth and final queen, also ruled for a short span of two years (1188 to 1186 BC).

All of these queens, including Hatshepsut, grappled with the persistent pressure of ruling amidst an unwelcoming court and the necessity of being succeeded by a male heir.

Nevertheless, Hatshepsut effectively governed ancient Egypt for over two decades, overseeing a period of splendor and maintaining a largely peaceful reign punctuated only by minor border skirmishes, all of which ended in victorious military campaigns, demonstrating her adeptness at maintaining equilibrium among the various spheres of power and securing the acceptance of her people.

Hatshepsut was one of the four children of Thutmose I and his great royal wife, Ahmose. However, her three brothers perished before reaching adulthood. Consequently, her father, renowned for leading Egypt through its greatest expansion at the time, designated her as the legitimate heir to the throne—a departure from the norm in ancient Egypt, where male heirs typically inherited.

Yet, deep-seated prejudices among the high officials of the court toward female rule led to a conspiracy orchestrated by the chief magistrate and the royal architect, resulting in the ascension of Pharaoh Thutmose II, born from Thutmose I’s liaison with another court woman and thus Hatshepsut’s half-brother.

Thus, she, a direct descendant of pharaohs, the rightful heir and holder of the title “Wife of the God,” had to content herself with becoming the great royal wife of her half-brother.

Their union bore only one daughter, the royal princess Neferure, and lasted for thirteen years until the demise of Thutmose II in 1479 BC.

Given that the elder of the two sons from another woman, the future Thutmose III, was too young to assume the throne, Hatshepsut was able to step into the role of regent.

In this position, she adeptly capitalized on the knowledge gleaned from her father and deftly negotiated with high officials such as Djehuty, the high priest and vizier Hapuseneb, and Senenmut, the second priest of Amun, who would later be appointed the queen’s architect.

This garnered her the support of the influential clergy of Amun, ensuring her retention of power to the extent that even after Thutmose III ascended to the throne, she continued to co-reign over Upper and Lower Egypt.

Throughout her lengthy reign, she spared no effort to validate her claim to the throne. Whether by reinforcing her divine lineage, adopting the name Maatkare—meaning “Truth (maat) is the Soul (ka) of the Sun God (Re)”—or identifying herself as Hatshepsut-Khenemetamun, “The first of the noble ladies united to Amun,” in certain monuments where her image appeared. She even donned the regalia of male pharaohs, including the headdress, the schenti skirt, and a false beard, eschewing any overtly feminine characteristics.

Backed by the clergy, she dedicated her rule to the construction and restoration of temples and other monumental works. The Red Chapel in Karnak, the largest obelisks erected up to that point, and the mortuary temple in Deir el-Bahari are credited to her reign. It was there, after being missing for 3,000 years, that Hatshepsut was finally rediscovered and rightfully restored to her place in history.

During this era of grandeur, Hatshepsut confronted six military campaigns, emerging victorious in each one. However, in the final two campaigns, Thutmose III assumed command of his troops, asserting himself as the Warrior King and signaling the resurgence of his influence within the palace, which heralded the beginning of Hatshepsut’s decline in power.

As Thutmose III’s authority grew, the queen experienced the loss of all her allies and loved ones within a span of just one year, from the influential clergy representative Hapuseneb, who had previously favored her, to her esteemed architect Senenmut, and even her daughter, Princess Neferure. Disheartened, Hatshepsut opted to retreat from the political sphere, granting Pharaoh Thutmose III unrestricted rule.

The most significant queen of ancient Egypt passed away in the solitude of her palace in Thebes. Following her demise, her monuments and inscriptions depicting her figure and name became targets of a campaign aimed at erasing her from history.

Initially, theories surrounding this persecution centered on an initiative by Thutmose III to prevent Hatshepsut’s relatives from laying claim to the throne by virtue of descending from a queen with divine lineage. However, subsequent investigations revealed that the erasure occurred gradually, particularly during the 19th and 20th dynasties.

Following Hatshepsut, queens Nefertiti and Tausert similarly met tragic fates and saw their memories persecuted. Despite concerted efforts to obliterate their existence, the diligence of researchers ensured their rightful recognition in the annals of human history.

Over 33 centuries after her death, archaeologist Howard Carter stumbled upon Hatshepsut’s sarcophagus in 1903, within the twentieth tomb unearthed in the Valley of the Kings (KV20). However, the discovery brought an unpleasant revelation: the queen’s mummy was not found inside.

In 2005, Zahi Hawass, the director of the Egyptian Mummy Project, initiated a new investigation aimed at resolving the mystery surrounding the location of Hatshepsut’s body. The focus was on identifying a mummy known as KV60A.

This mummy was discovered without a coffin and devoid of the customary treasures typically accompanying pharaohs. However, its positioning was significant: the left arm was bent in the traditional manner observed in deceased queens.

It’s often said that history is penned by the victors, but no one remains triumphant indefinitely. Similarly, history eventually places everyone in their rightful position, and in this instance, that’s precisely what occurred.

Archaeologists had been aware of Hatshepsut’s existence long before the discovery of her mummified remains. However, the persecution she endured, coupled with her remarkable achievements, facilitated the reconstruction of her story—a narrative previously shrouded in myth due to attempts to erase her memory. Today, Hatshepsut’s legacy has been reinstated, affirming her as one of the legitimate occupants of the ancient Egyptian throne.

Source: Anna Tomas, La Vanguardia