The pharaoh stands out as perhaps the most renowned facet of Ancient Egypt, yet simultaneously remains one of the most enigmatic figures. Surely, if one were to inquire of passersby on the street regarding this historical persona, they would readily conjure names such as Tutankhamun, Khufu, or Ramses II, along with iconic symbols like pyramids.

While representations of this institution abound in films, documentaries, and video games, delving deeper into the pharaoh’s role beyond mere rulership often stumps many.

In the following discourse, we shall delve into the responsibilities and symbolism surrounding the ancient Egyptian pharaohs, the formidable leaders of their era.

Symbolism of the Egyptian Pharaohs

An intriguing facet of the Egyptian pharaohs lies in the etymology of their title. The term itself derives from the Egyptian phrase “per-aa,” meaning “big house,” which originally referred to the royal palace encompassing the pharaoh’s court.

Notably, it wasn’t until the illustrious 18th Dynasty (1550-1295 BC)—renowned as the pinnacle of Egyptian history—that this term expanded to encompass the monarch themselves. While the prevailing designation for the ruler was “Nsw” (pronounced “nesu”), signifying kingship or sovereignty, we shall adhere to the term “pharaoh” in this discourse for its widespread usage and accessibility.

The genesis of the Egyptian pharaohs and their symbolism can be traced back to the twilight of the predynastic era (circa 3200-3100 BC), extending onward to the grandeur of the Old Kingdom (2686-2125 BC).

During the predynastic period, prior to the ascent of the inaugural official pharaoh, Narmer, several quintessential pharaonic motifs emerged. These included the ceremonial mace, the iconic white and red crowns, and the invocation of the name of Horus.

Of these, the appellation of Horus stands out as the foremost among the five names bestowed upon Egyptian pharaohs, representing a cornerstone of their identity and authority.

It is imperative to recall that the pharaoh occupied a dual role as both monarch and divine entity. Rooted in ancient Egyptian mythology, the narrative unfolds with the god Horus assuming rulership over Egypt following the demise of his father, Osiris.

Consequently, the mantle of Egyptian pharaohs inherits this mythic legacy, with their representation mirroring that of the divine. Upon coronation, the pharaoh embodies the essence of Horus, only to transition into the realm of Osiris upon death.

The white and red crowns serve as potent symbols of the pharaoh’s dominion over Egypt. While depictions of kings adorned with the white crown, emblematic of Upper Egypt, have been unearthed, it wasn’t until the unification of Egypt by Narmer that the red crown, representing the governance of Lower Egypt, made its appearance. Thus, these two crowns were melded to create the double crown, symbolizing the amalgamation of Egypt under a singular ruler.

In addition to the crowns, the symbolism surrounding Egyptian pharaohs encompassed an array of ornamental elements adorning their attire and accessories.

The Was-scepter, symbolizing “power” and “dominion,” featured prominently, while the crook and flail (heka and nekhakha), typically wielded together, held significance as well. The former denoted mastery over the populace, akin to shepherding livestock, while the latter represented the capacity to lead and direct them.

Further protective accouterments included the uraeus, embodying the snake goddess Wadjet, often situated atop the nemes or double crown. The nemes itself, a distinctive headdress, occasionally substituted the double crown, serving as a symbol of regal authority. The blue crown, associated with martial prowess, and the false beard, likely a homage to the god Osiris, rounded out the panoply of pharaonic regalia.

Coronation of the Egyptian pharaohs

The coronation of an Egyptian pharaoh was a momentous occasion steeped in tradition and symbolism. Following the funeral rites of their predecessor, the successor assumed the mantle of pharaoh, adhering to the longstanding Egyptian custom wherein the son conducted the burial of his father, thereby solidifying his claim to the throne. This act transformed the deceased pharaoh into the divine figure of Osiris, while his successor assumed the role of Horus.

While precise details regarding the coronation ceremony are scarce, it is believed that during the Old and Middle Kingdoms (2686-1650 BC), the coronation often took place in the temple of Ra at Heliopolis. Subsequently, from around 1550 BC onward, the ceremony shifted to the temple of Amun at Karnak.

Functions of the Egyptian pharaohs

On the day of coronation, the pharaoh would be roused at dawn and attired in regal garb within the confines of his chambers, preparing him for the solemn rituals ahead. Accompanied by priests, he would proceed to the temple where purification rites were performed, ensuring his spiritual cleanliness before the gods. Symbolic acts, such as being ritually breastfed by a goddess, likely Isis, and receiving the double crown and scepters of power in the presence of the divine assembly, marked key moments in the ceremony.

To complete his ascension, the pharaoh would traditionally undertake a ritual circuit around the walls of the city of Memphis. However, over time, this practice evolved into a symbolic journey across the land to receive the blessing of Horus. Following the culmination of these rituals, the newly crowned pharaoh would host a banquet to commemorate his accession to the throne.

Following the conclusion of these solemn events, the Egyptian pharaohs promptly commenced their daily duties. At the break of dawn, the ruler would undergo a ritual of purification, cleansing himself with the aid of attendants dedicated to his personal hygiene.

Subsequently, it is presumed that the pharaoh would make offerings to the gods and engage in communication with them. While some suggest that these rituals occurred twice daily, the demanding schedule of the pharaoh renders this scenario improbable. Indeed, it is more plausible that the monarch occasionally delegated these responsibilities to priests in his absence.

Following these religious observances, the pharaoh would partake in a light repast before proceeding to confer with the vizier, his most trusted advisor and the chief administrator of the realm on behalf of the pharaoh. The vizier served as the repository of information concerning all matters within the kingdom.

It is likely that the pharaoh’s interactions with the vizier were a daily occurrence, as the monarch’s primary duty was to ensure the stability of the realm, known as maat. In addition to these consultations, the pharaoh may have received visits from notable figures, including foreign envoys and prominent nobles of the Egyptian state.

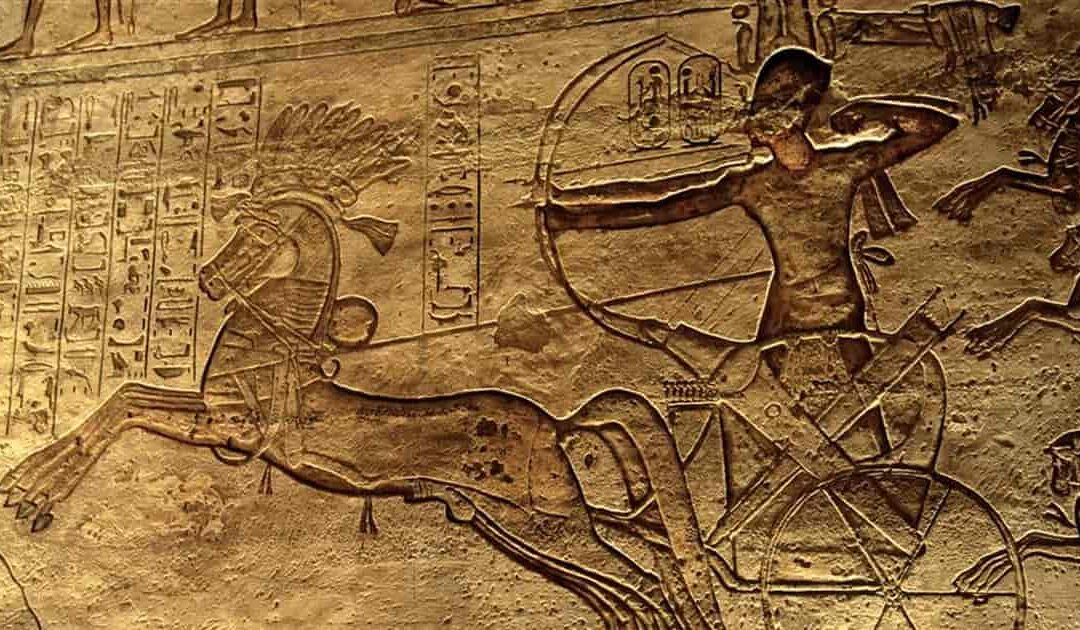

On another note, the pharaoh held the esteemed position of commander in chief of the Egyptian army. Typically, it was the pharaohs themselves who led military expeditions to expand and safeguard their kingdom, though exceptions existed.

The military role of the pharaoh encompassed two primary aspects: geopolitical and religious. Geopolitically, the monarch sought to safeguard Egypt’s strategic interests, while from a religious standpoint, the state represented the Egyptians’ entire world—a sanctuary amidst a sea of chaos perpetually threatening destruction.

In this context, the pharaoh assumed a divine mandate as the guardian of stability, a celestial entity shielding his lands from the ravages of chaos. Hence, it’s commonplace to encounter depictions of pharaohs vanquishing adversaries in temple bas-reliefs.

Following the fulfillment of his daily obligations, the pharaoh might indulge in leisure activities during his leisure time. Nonetheless, the life of a pharaoh was marked by relentless activity, and leisure time was likely less abundant than commonly perceived.