In September of 1900, at the height of Egyptology and at the scene of excavations carried out eight years earlier, a remarkable discovery was made. The culprit behind it, however, was a donkey.

This is not a figure of speech—the donkey was pulling a cart down Bab el-Molouk street, in the Karmouz neighborhood of Alexandria, when the ground gave way beneath its feet and it disappeared from sight.

The hole was about twelve meters deep and inside was a splendid network of Roman burials from the early imperial age. More specifically, from the 1st and 2nd centuries AD.

In fact, it is believed that they were not originally catacombs but rather the private mausoleum of a wealthy family, which was later put to public use for no known reason and means that today there are more than three hundred burials. The complex is located next to the western necropolis and could be considered a continuation of it.

Nothing remains of the structures on the surface; the first of its three levels are below ground. However, the tombs are distributed around a large roundabout through a network of underground tunnels carved into rock.

The two lower levels were submerged underwater, though since 1995, only the deepest one, which probably connected with the Serapeum (a temple dedicated to Serapis, patron deity of Alexandria), remains below water.

The hapless donkey fell through an access shaft, not through the main entrance, which is equipped with a spiral staircase and turns around a well about ten meters deep by six wide. This served to provide natural light despite the small niches to place oil lamps on the side walls.

The stairway had smaller upper steps because the Romans believed that after visiting the deceased, they lost strength as they ascended, which is why those closest to open air almost constitute a ramp.

Going down the stairs, you come to a vestibule with two niches that give way to a circular room with a colonnaded island in the middle and six pillars supporting a dome.

It is the axis from which everything is articulated, because to the left there is a triclinium with divans that, according to an inscription, were covered with cushions (a triclinium was a type of dwelling used for ritual banquets, in this case it was of obvious funerary character).

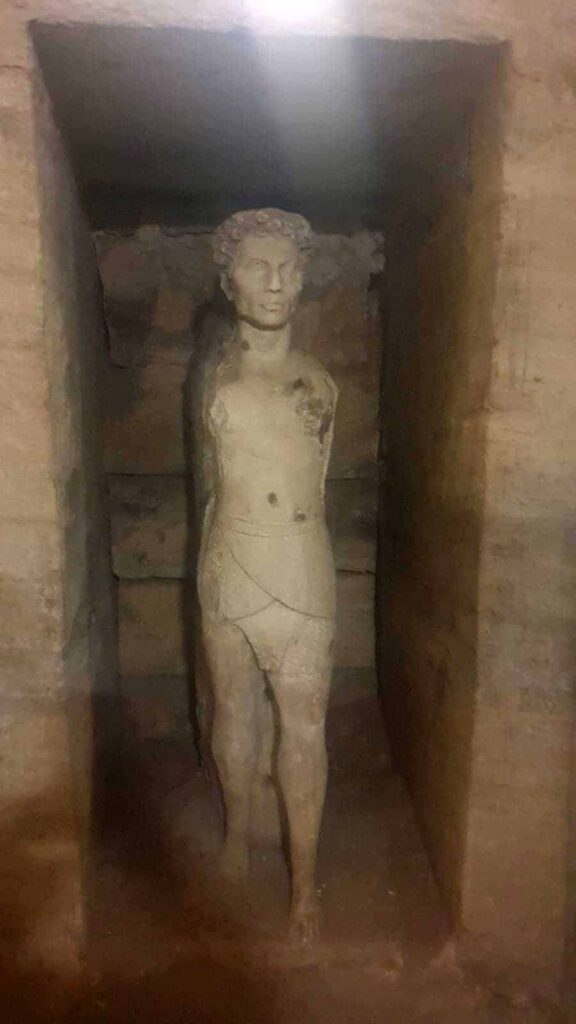

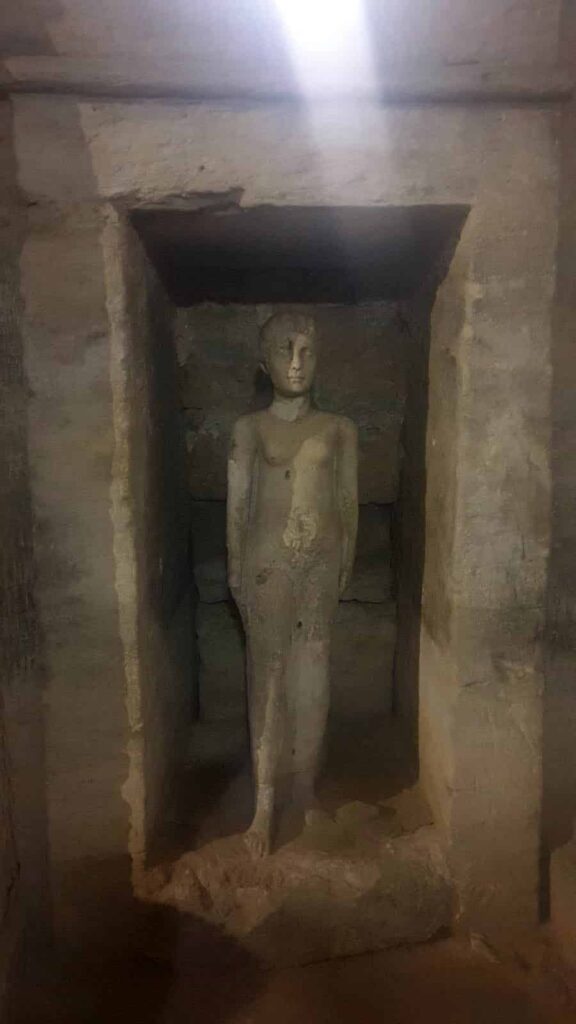

In the background was a small chamber decorated with two statues.

From that roundabout, you descend to the next level through a breach in the wall, of which the creation-date is unknown.

This opens before the visitor in what is possibly the most curious corner of the place, the Hall of Caracalla.

It is named after the Roman emperor, though he is not buried inside. He was very fond of horse racing, however, so his horses were buried there in around 215 AD.

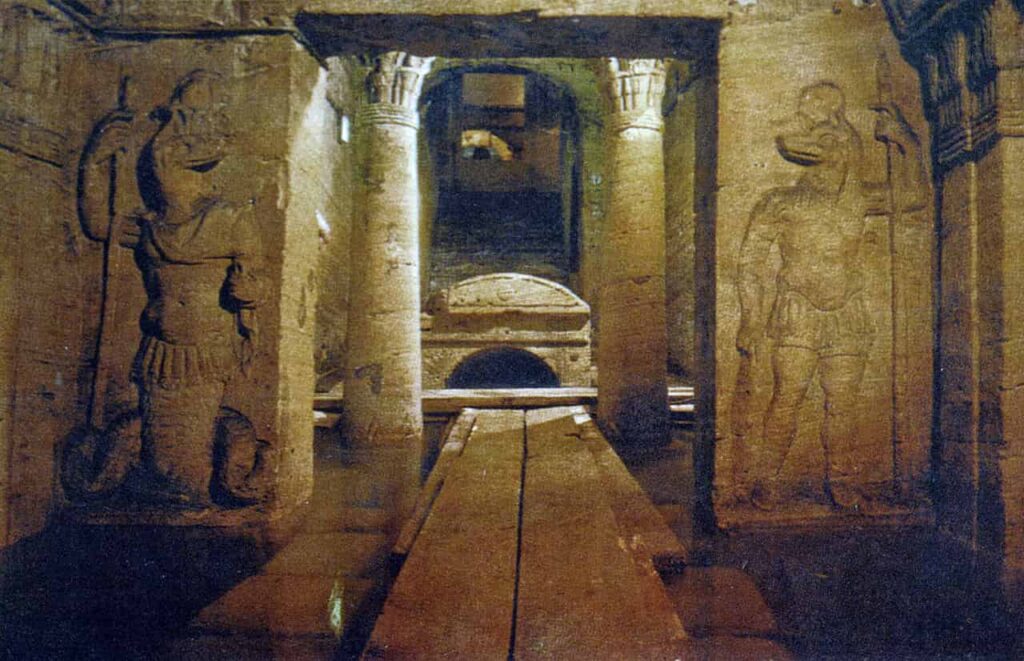

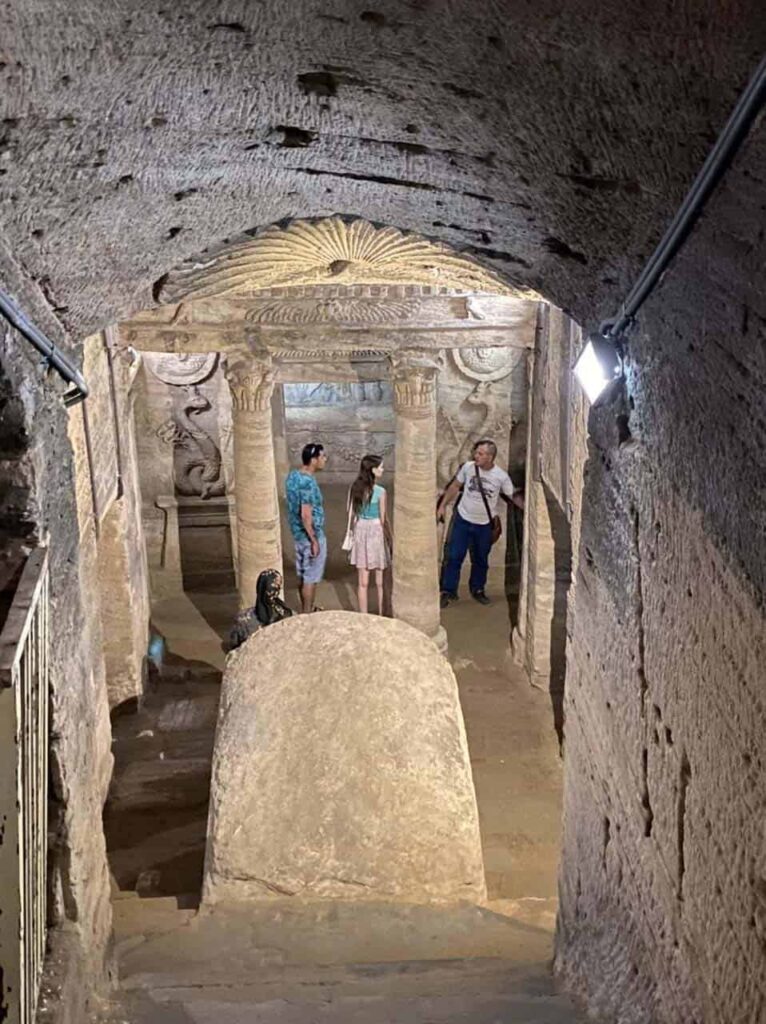

The burial chamber’s main entrance is a lintelled temple, supported by two columns of capitals in the shape of papyrus, lotus, and acanthus leaves, which were typical of ancient Egypt.

The architrave above shows a relief of a winged sun disk flanked by figures of Horus as a falcon.

Once past that entrance, there are two serpentine agathodaemon (a spirit or Greek demon of the vineyards and cereal fields that the Romans assimilated to their genii of fortune and used to associate with banquets), each crowned by the pschent (the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt) and carrying a Roman caduceus (a staff topped by wings with two intertwined serpents, a symbol of medicine and used by Mercury, the guide of the dead), and a Hellenic thyrsus (a stick lined with vines or ivy with tied bows and a pineapple as a finial. It was of Egyptian, or perhaps Phoenician, origin).

On the snakes, there are two medallions with the face of Medusa.

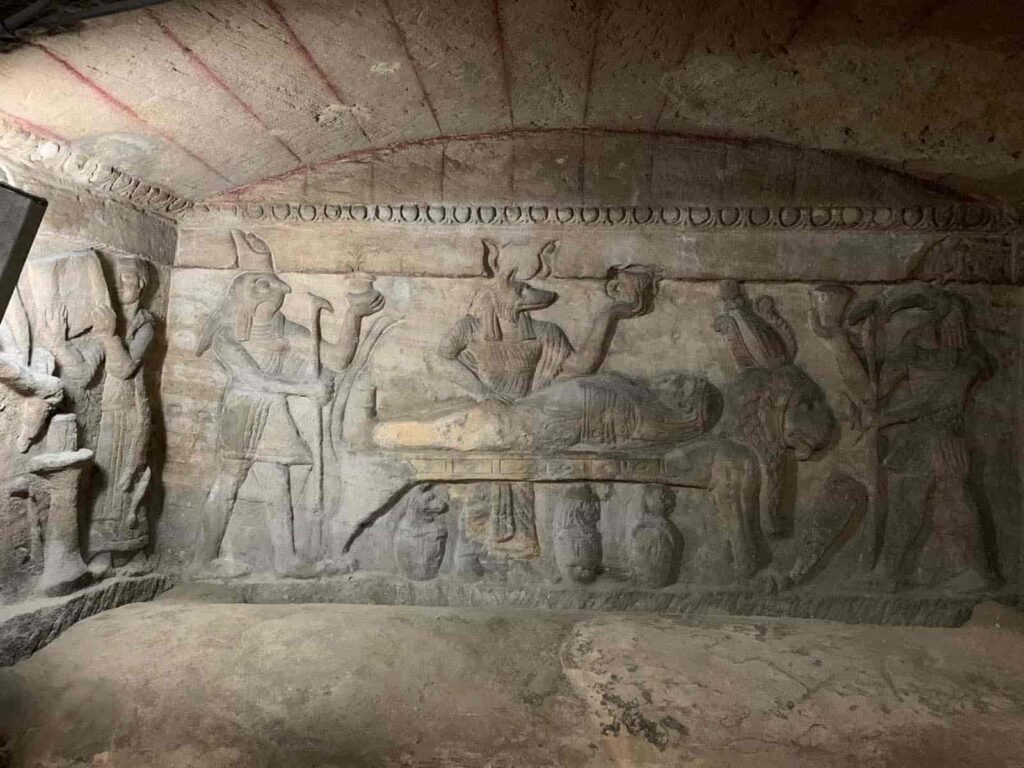

The interior of the chamber itself is adorned with two large figures of theriomorphic gods in relief on the wall (Thoth and Anubis), although there is also a man and a woman.

The former is represented with the characteristic Egyptian hieraticism, and the latter with an unmistakably Roman hairstyle, an example of artistic syncretism of the many styles.

The space is divided into three niches, each with an enormous stone sarcophagus and peculiarly immobile lids. The bodies they contained entered through openings made from a passageway that runs along the outer perimeter of the chamber to its rear.

Each sarcophagus, decorated with garlands in relief, is associated with a funerary scene, also in relief. At the center, Anubis is seen dressed as a Roman legionnaire mummifying a body, deposited on a bed in the shape of a lion, and the corresponding canopic vessels underneath. The sides are dedicated to the ox-god, Apis.

Apart from this original burial chamber, Kom el-Shoqafa has a network of tunnels that were reused to house later burials, drawing comparisons with the catacombs of Rome.

However, the name of the site has nothing to do with it. It means “Mound of Shards” and was named after the thousands of terracotta pieces found there from the ceramic jars thrown by relatives of the deceased.

These people brought them alongside food and drink to consume during funeral services and would smash the jars after finishing as they did not want to take them home after using them at a funeral.