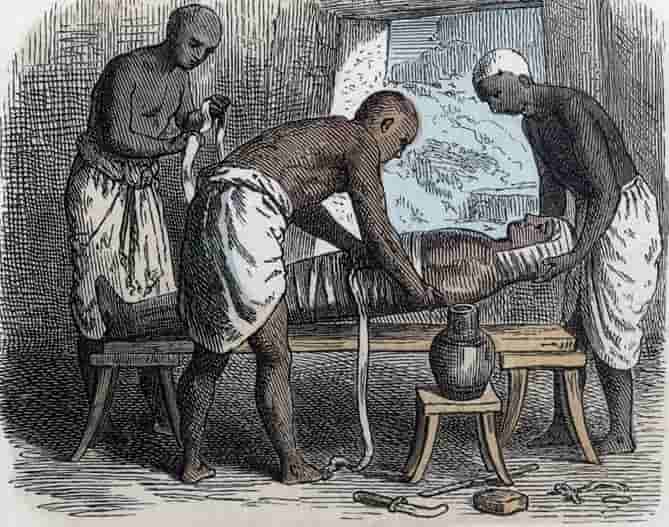

The chemistry behind the ancient Egyptians’ quest for eternal life has been shrouded in mystery for centuries. Since Howard Carter uncovered the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922, archaeologists and researchers have made significant advancements in understanding the techniques and tools used for mummification. However, many secrets surrounding the ancient process still remain unsolved.

In 2016, an archaeological team discovered a 2,500-year-old embalming workshop in the Saqqara necropolis, located near the pyramid of Unas, the last pharaoh of the Fifth Dynasty.

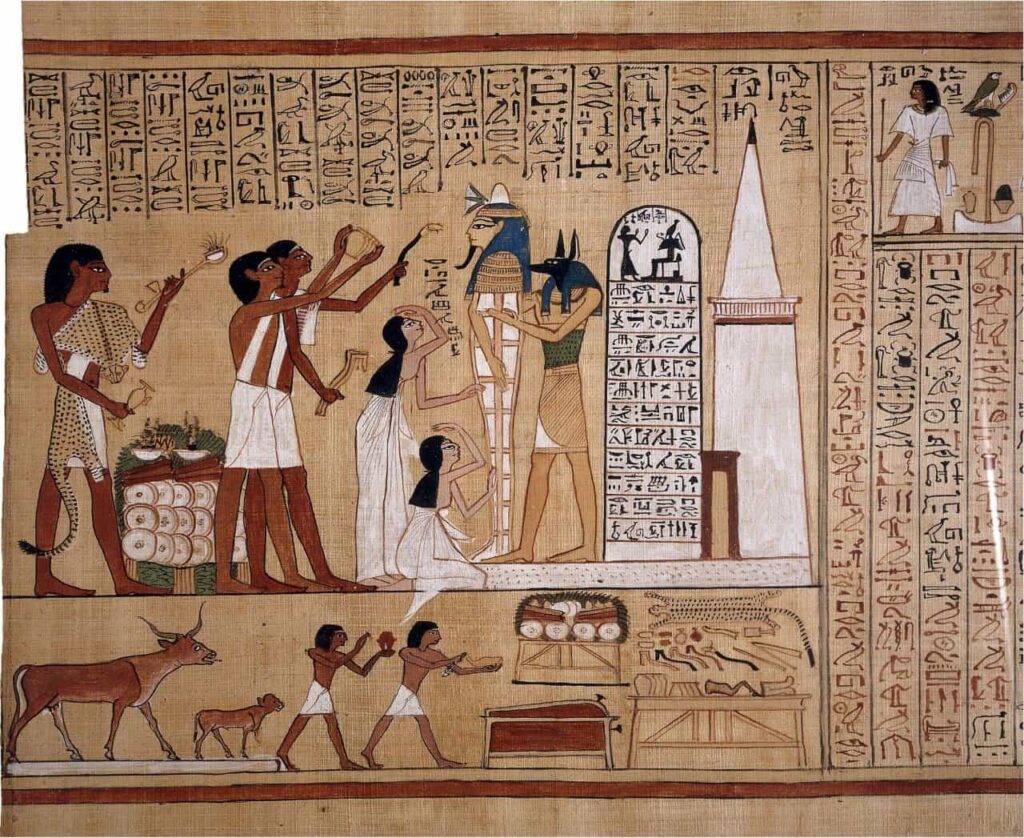

The workshop, dating back to the Late Period (664-525 BC), featured a room known as the “wabet,” where the evisceration of bodies took place. The site contained numerous jars, labeled with the contents used to preserve plant and animal extracts, which would later be employed in the mummification process.

Unknown Ingredients

Researchers from LMU University of Munich and the University of Tübingen, in collaboration with the National Research Center in Cairo, conducted a study of these vessels and their contents, published in the journal Nature.

The study utilized advanced techniques such as mass spectrometry and gas chromatography, enabling the detection of many of the substances used by ancient embalmers. The most significant finding was the discovery of previously unknown substances and mixtures.

The experts believe that recovering these containers, with their labeled contents and instructions for use, presents a unique opportunity to gain new insights.

For example, the study notes that pistachio resin and castor oil were only used on the head, while certain containers contained specific formulas for treating the liver and stomach.

According to Philipp Stockhammer, an archaeologist at LMU University and one of the study’s authors, “Egyptologists could only speculate about the meaning of these substances. We now know, for the first time, what terms like antiu mean.” The term “antiu” was previously translated as myrrh or incense, but the study showed that it refers to a mixture of various ingredients.

The Origin of the Substances Used by the Ancient Egyptians to Achieve Eternal Life

Researchers have discovered two surprising substances that were used by the ancient Egyptians in their quest for eternal life. These substances are a resin called elemi, which comes from the Canarium trees in the rainforests of Asia and Africa, and dammar, which comes from a type of tree known as shorea that grows in the tropical forests of southern India, Sri Lanka, and Southeast Asia.

“Egypt was resource poor in terms of resinous substances, so many of these substances were obtained through trade from distant lands,” says Carl Heron of the British Museum in London.

It’s unclear whether the ancient Egyptian embalmers specifically sought out these ingredients, or if they stumbled upon them through trial and error. According to Salima Ikram, an Egyptologist at the American University of Cairo, “Absolutely unbelievable. Who would have thought they were getting materials from as far away as India?”

The authors of the study suggest that the ancient Egyptian embalmers had a deep understanding of the properties of the raw materials they used. The containers analyzed in the study contained complex mixtures that, in some cases, had been carefully heated or distilled.

Many of the resins used also had antimicrobial properties, which helped to preserve the body. In one of the jars, there was even an inscription that read, “So that its smell is pleasant.”

Maxime Rageot, a biomolecular archaeologist at the University of Tübingen, suggests that the recipes used by the ancient Egyptians to embalm bodies became increasingly complex over time. However, the main question that researchers have yet to answer is how the ancient Egyptians developed these specific embalming procedures and recipes, and why they chose certain ingredients over others. Mahmoud Bahgat, a biochemist at Egypt’s National Research Center in Cairo, believes the answer is simple, “We need to be as clever as they were to figure out their intentions.”

Source: JM Sadurní, National Geographic