The word “sarcophagus” originates from the Greek word “Sarkophagos,” adopted by Latin, which means “that eats the body” in a figurative sense. It is notable that the ancient Egyptians referred to it as “the lord of life,” considering it a dwelling place for the deceased that housed their mummified and eternally incorruptible body—a microcosm where the deceased was placed.

Therefore, its lid was associated with the celestial vault and consequently with the goddess Nut, while the box, where the body rested, was connected with the earth god Geb, symbolizing the deceased’s participation and fusion within the cosmos.

However, the earliest ancient Egyptian dead were not interred in sarcophagi. During that time, the deceased were directly buried in the sand, which acted as a natural dehydrator, preserving them perfectly.

Between the end of Naqada III and the beginning of the First Dynasty, tombs became more elaborate, and the deceased bodies began to be exposed to the air. Thus, there arose a necessity to add an element to protect them, initially involving wrapping the body in animal skin.

The evolution of tombs and the protection of the deceased continued throughout the Thinite Period (Early Dynastic Period). This period saw the introduction of the practice of using ceramic containers resembling eggs and later small rectangular wooden sarcophagi, where the body was placed in a contracted position.

Intermittently during Dynasty III (more frequently in Dynasty IV), traditional sarcophagi appeared—longer than their predecessors—allowing the deceased’s body to stretch. This adaptation was in response to the need to access the abdomen during the mummification process, enabling the incision through which the viscera were removed for separate embalming.

This element also has significance in ancient Egyptian mythology, as a sarcophagus was used to enclose the body of Osiris when he was murdered by his brother Seth.

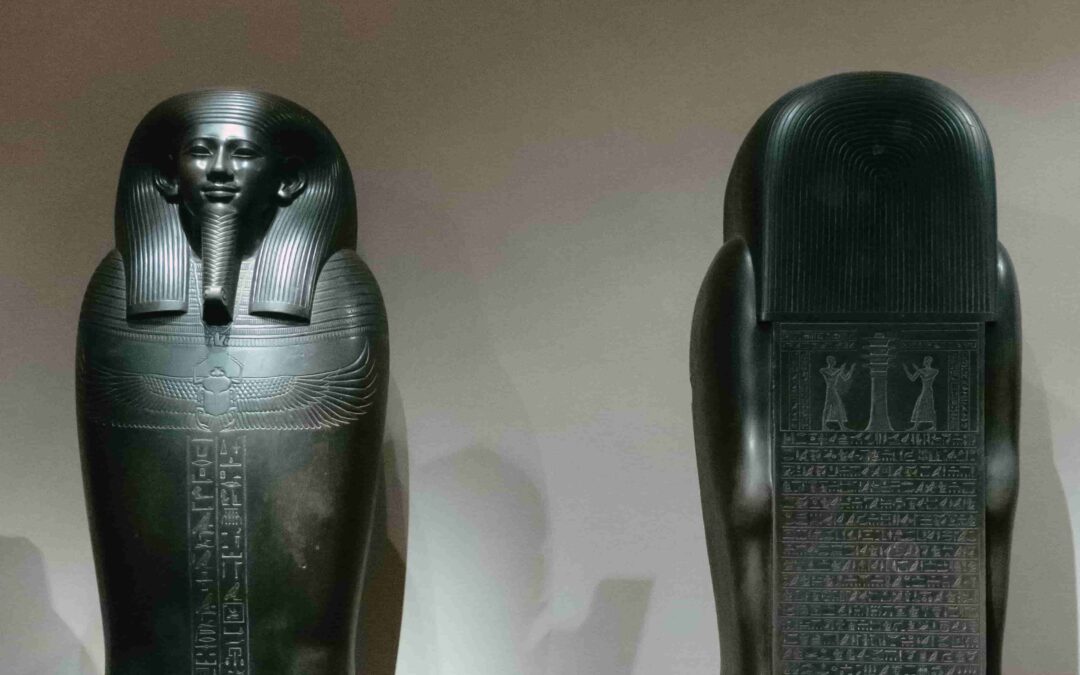

The ancient Egyptian deceased were sometimes buried in a series of sarcophagi arranged and nested within one another. These sarcophagi could be rectangular (known as “qersyu”) or anthropoid, with the latter usually being the internal ones (“suhet”).

The first wooden anthropoid sarcophagus emerged in the New Kingdom with Userhat and in stone with Merymose, Viceroy of Nubia during the time of Amenhotep III.

The entire surface of the sarcophagus could be decorated, undergoing different stages of evolution. In the Old Kingdom, it was common to engrave what we traditionally know as “Palace Facades.”

In the Middle Kingdom, some magical inscriptions were added, including two Eyes of Horus, through which the deceased could perceive their “journey,” and a small “door.”

Subsequently, more iconography was progressively added, incorporating protective gods who ensured their well-being through certain apotropaic formulas.

This tradition reached its pinnacle in the Third Intermediate Period. Since then, examples of great beauty have been discovered, with inscriptions both on the exterior and covering the interior walls of the sarcophagus, depicting scenes from the sacred funerary books.