The sycamore tree, revered for its protective and nourishing qualities, held significant symbolism in ancient Egyptian tradition.

In many instances, the symbolism surrounding certain images in their context led to deeper insights. This was particularly notable in ancient Egypt, where magic and humanity intertwined, often manifesting through the external form of objects linked to deities with distinct characteristics.

Ancient Egyptians didn’t aim to replicate reality but sought to imbue presence and form into the realities represented under various masks, embodying their true essence.

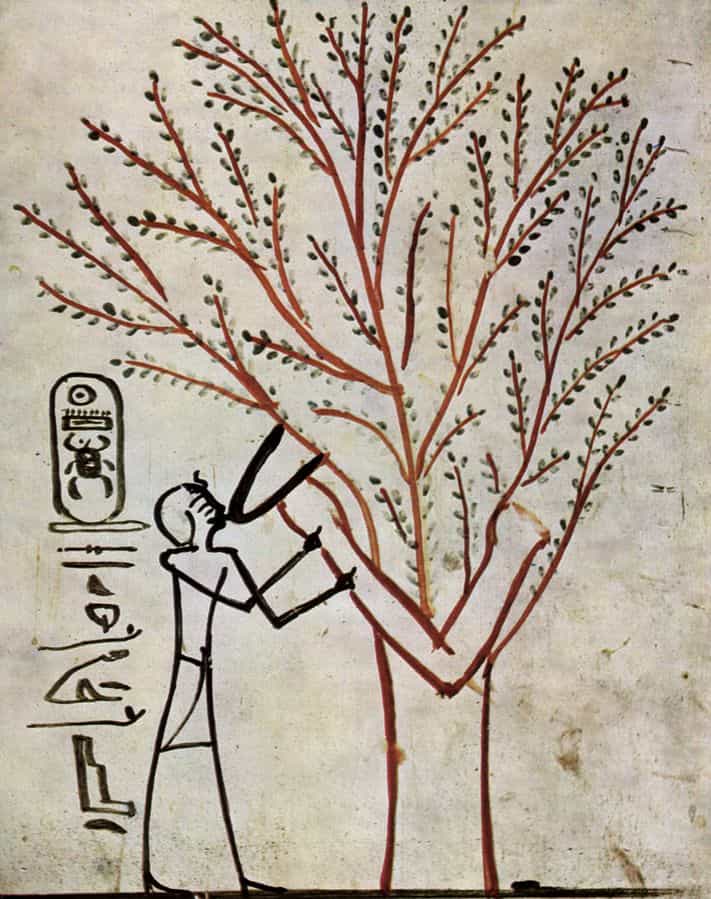

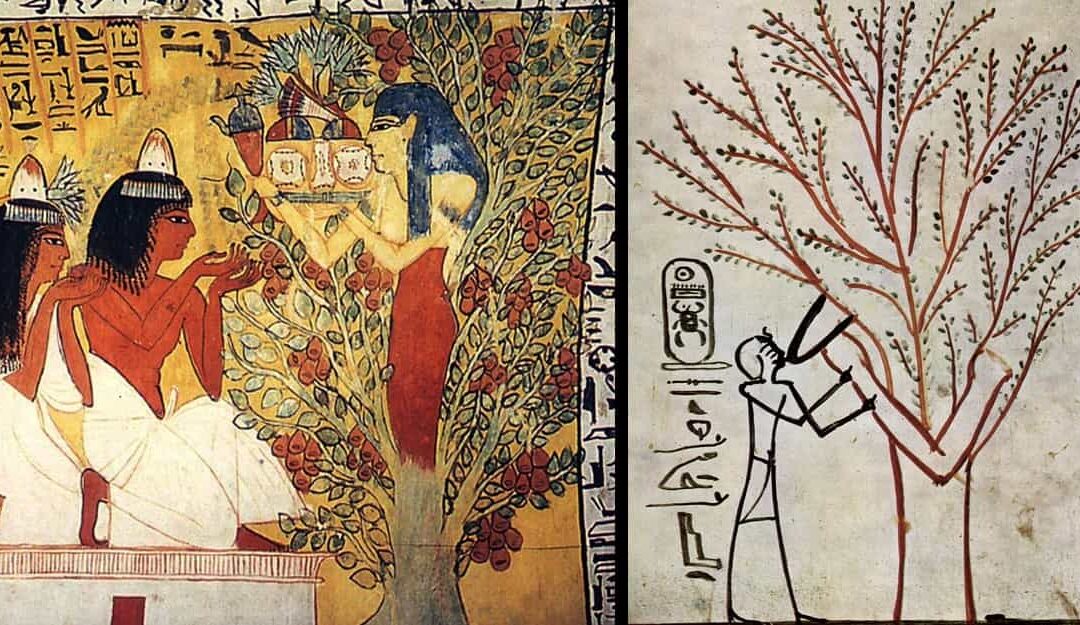

The personification of “Nht” (sycamore) took the form of a tree-goddess, associated with deities like Hathor, Nut, and Isis, and was connected to the passage to the Hereafter. Isis was also known as “the Lady of the Sycamore.”

This personification varied in form, sometimes appearing formal, sometimes emblematic, depending on the context. Despite limitations within a chronological framework, the symbolic function and manipulation of codes remained potent, portraying the image as tangible, serving as a conduit between different spheres or worlds, and as a distinct axis bridging heaven and earth—the tree of life.

Cosmogonies and creation myths stemmed from observations of natural processes, often cyclical in nature. Their association with various deities showcased a multitude of approaches, enriching the interconnectedness of various images and imparting them with a sense of totality.

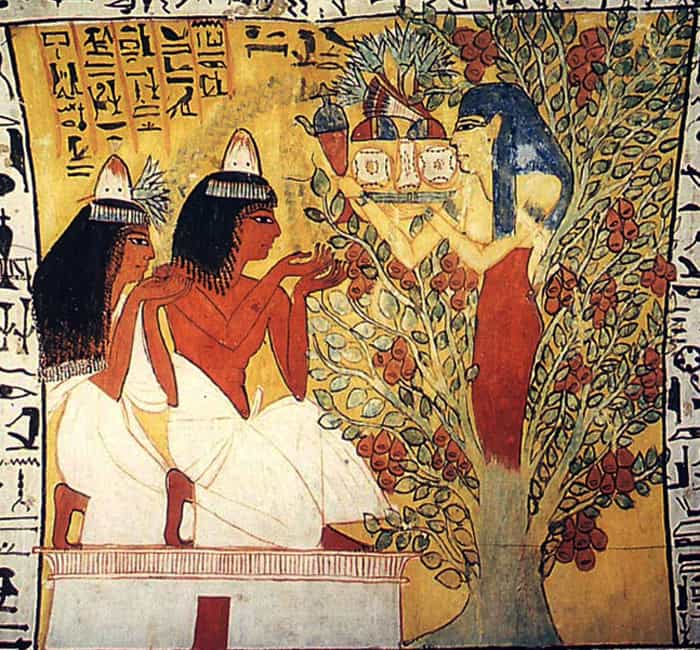

In this instance, the “Lady of the Sycamore” is an integral part of the Osiriac cycle, intricately linked to Ra/Osiris. Consequently, the goddess represented by the sycamore embodies multiple facets, including Hathor, known as the “Lady of the Theban mountain,” Nut-Hathor, often referred to as “the celestial cow,” and Isis, revered as the “mother of Horus,” among others.

These manifestations trace back to the archaic figure of “meret-uret,” symbolizing heavenly concepts such as the abode of Horus or the cosmic mother. Therefore, it’s important to understand that while different names are sometimes used, they all represent a singular essence.

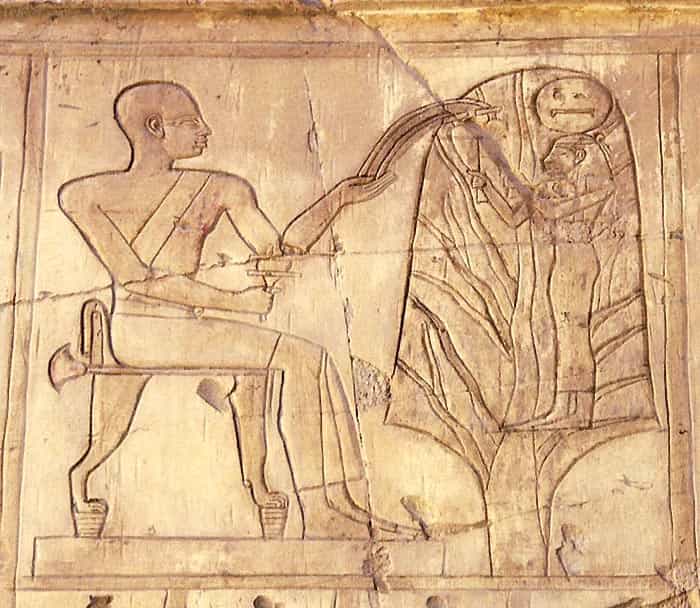

Regarding the sycamore, its association with Nut as the “heavenly mother” is notable, as this wood is commonly used for sarcophagi. Within these sarcophagi, the carving of Nut, known as “the one who covers the sky,” embraces the deceased, symbolizing a return to the mother’s womb. Such representations date back to the Old Kingdom and the Middle Kingdom, often depicted in statuary of private family groups.

In more symbolic contexts, depictions of the rising sun (Ra) often feature two mountains resembling the breasts of a goddess. Additionally, references are made to the medicinal properties of sycamore sap, used in various remedies. Furthermore, the sycamore is linked to Horus and his healing during his conflict with Seth.

The scenes featuring the sycamore are commonly found in tombs typical of the New Kingdom. During this period, burials were conducted in tombs dug into the ground, leading to the symbolism of the tree representing the Theban mountain, symbolizing the entrails of the earth under the dominion of the goddess Hathor.

Following this line of thought, it’s understood that despite the burial being underground, the deceased must undergo a series of trials and ultimately emerge victorious towards the dawn of a new day.

The Osiriac cycle guides the departed on a journey through the Duat, where a goddess, sometimes linked with Imentet and associated with the desert’s entrance, must conquer the final hour of the day to emerge alongside Ra.

Understanding this symbolism requires situating ourselves within the cultural context. Ancient Egyptians perceived the desert as a hostile terrain, contrasting sharply with the ordered and secure realm of the garden—a sanctuary isolated by towering walls, offering cool respite and contrasting sharply with the chaotic nature of the desert.

This “paradise” found expression on tomb walls, adorned with depictions of lush gardens and sacred trees, intended for the eternal pleasure of the deceased. These sacred trees, notably the sycamore, played a pivotal role, providing sustenance, protection, and facilitating the transition to the afterlife.

The sycamore, specifically, serves as a crucial element for departing the underworld, harnessing divine energies to achieve immortality. Its association with life and rebirth often places it near water sources, while its unoutlined leaves symbolize perpetual growth.

This hierophany isn’t confined to the desert alone; it also manifests within the orderly confines of the garden, where the departed freely roam, quench their thirst, and find solace among the tree branches (Ba).

It perhaps echoes the mythical moment of creation atop the primeval mountain, where the first trees sprouted and the sun paused before its ascent—a recurring motif mirrored in the ascent of departed souls.