The Temple of Khonsu stands as a striking exemplar of New Kingdom religious architecture. Its significance as one of the most scrutinized and photographed temples stems from its exceptional preservation within the confines of the Karnak sanctuary in Thebes.

Khonsu, alongside Amun-Ra and Mut, constituted the Theban triad. This triad comprised two mature deities and one youthful figure, Khonsu himself. Revered as a lunar deity, Khonsu assumed roles as a guardian of the infirm, a banisher of malevolent spirits, and a patron of fertility and childbirth.

Within the temple’s intricate reliefs, Khonsu is depicted in dual forms: as a mummified child adorned with a distinctive side ponytail and goatee, or as a majestic falcon, each adorned with either a full or crescent moon, symbolizing his lunar association.

While convention may suggest a familial dynamic among the triad, with Mut as Amun-Ra’s spouse and Khonsu as their offspring, historical insight reveals a more nuanced reality.

Rather than familial ties, these three deities, originating from disparate traditions, were interconnected within a unified pantheon, sharing sacred space within the sanctuary despite their diverse origins.

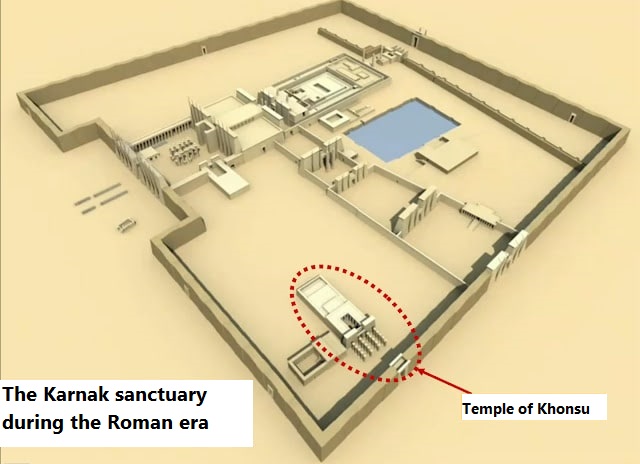

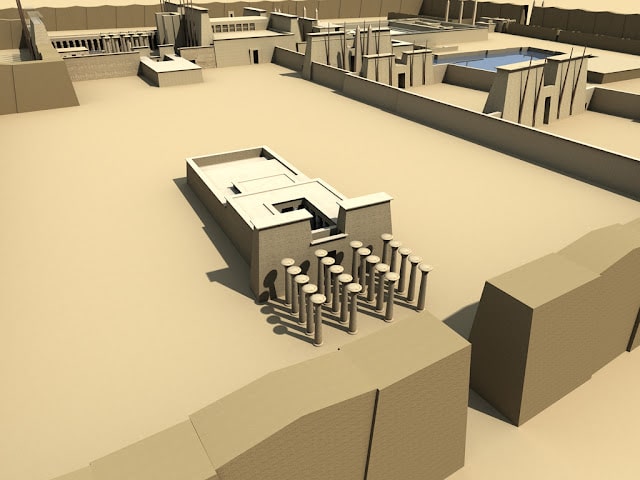

Khonsu’s abode resides within a modest temple situated in the southwest corner, secluded from the surrounding structures. Its inception traces back to the reign of Ramses III (1184-1153 BC), a pharaoh of the 20th dynasty. However, the construction extended into the Ptolemaic era, resulting in diverse pharaonic influences evident throughout the temple’s chambers.

Excavations beneath various rooms unearth remnants hinting at earlier constructions. During the reign of Taharqa, king of the 25th dynasty (690-664 BC), a colonnaded entrance portico was appended to the pylons. Only fragments of columns bear testament to this addition.

Nectanebo I (380-362 BC) envisioned a new pylon, accompanied by an avenue of sphinxes linking it to the temple. Regrettably, this project remained incomplete, with only the entrance gate, now known as Bab el-Amara, remaining. Ptolemy III (246-222 BC) adorned this gate with reliefs during his reign.

Under the same pharaoh’s rule, sanctuaries were annexed to the rear and side (Opet) of the temple. Historical records indicate the presence of a sun chapel atop the roof, accessible via stairs from the antechamber. Despite the passage of time, the temple has endured, retaining a relatively well-preserved state.

The fundamental framework of this edifice adhered to the typical layout of religious enclosures during the New Kingdom era, making it a quintessential model for illustrating the characteristic design of freestanding Egyptian temples.

The temple’s structure revolved around a longitudinal axis, symbolizing the Nile River’s course through the heart of Egypt. Furthermore, its architectural design orchestrated a gradual convergence of the ceiling and floor within the chambers upon entry, resulting in a diminishing illumination until complete darkness enveloped the interior.

Adorning the walls and columns of the temple were intricate reliefs and paintings depicting the Theban triad and the pharaohs responsible for its construction. These embellishments were added at various intervals, contributing to the temple’s evolving aesthetic over time.

The structure of the temple encompasses various components:

- An extensive avenue lined with sphinxes sporting ram heads, leading to the grand entrance of the temple. These sphinxes served the dual purpose of guarding and protecting the sacred precinct.

- The pylons, characterized by two towering structures with a trapezoidal profile resembling a sloping shape, provided access through a lintel door into the interior. Symbolically, they represented the barriers akin to the Nile’s traversal into Egypt and the mountains where the sun ascended on the horizon. Externally, recesses housed four cedar poles bearing banners of the gods, fluttering in the breeze, while the robust towers symbolized the mystical assurance against intrusion of disorder into the temple.

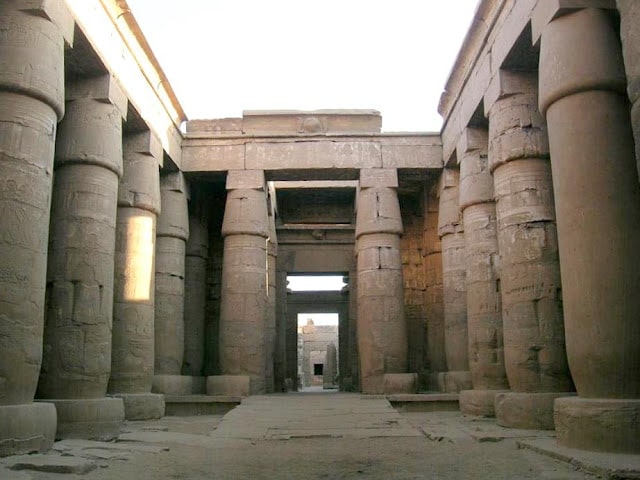

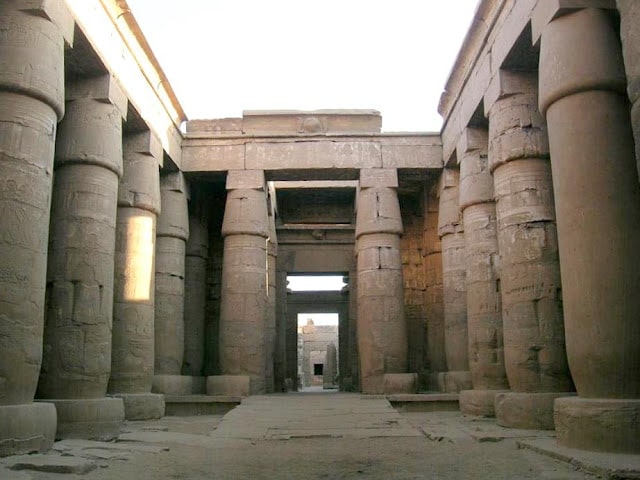

- Upon crossing the threshold, a sequence of courtyards unfolded, starting with the hypetra hall or porticoed patio, enclosed on three sides. Massive ashlar columns, featuring capulliform capitals, adorned this space, embellished under the patronage of Ramesses.

- The hypostyle hall marked the transition into more confined quarters, its roof supported by eight columns. Adorned with reliefs and paintings portraying the celestial sky, the hall depicted the pharaoh’s role as an intermediary with the gods, offering homage and conducting rituals in honor of Khonsu. Dim lighting further heightened the mystical ambiance.

- At the rear lay the sanctuary, housing the deity’s statue and all paraphernalia associated with his worship, shrouded in darkness. Comprising various chambers, including the sacred boat room, storerooms, and the innermost cella, the sanctuary served as the epicenter of religious devotion.